Bruce Williams was my best friend for nearly all the years I was a teacher. Although he wasn’t happy when I told him I was retiring, I knew that we would keep in close contact from wherever I traveled. Then, suddenly and sadly, he died, twelve years ago, on March 27, 2001. For awhile afterward, Karen and I would have an adventure or meet an interesting person, and I would say to myself, “I’ll have to remember to tell Bruce about this.” Then I’d remember he was dead. I still think sometimes, “I bet Bruce would appreciate this.” So much has happened to both of our families since that day. His son got married. His daughter, my goddaughter, has a new life in San Francisco. His wife survived a terrible illness. Karen and I have a granddaughter. Life goes on, as they say. Sometimes I wish it didn’t. That we could all be forever young.

Here is the eulogy I gave for Bruce’s memorial at the college, held a few weeks after his death. Bruce, I hope you are still resting in peace.

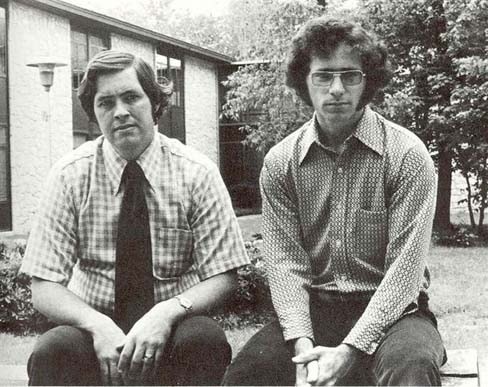

I could tell you a hundred anecdotes and stories about Bruce. I have known him for 31 years. He was my first adult friend, and there was a time when we spoke on the telephone almost every day. We played basketball nearly every day for 25 years; we spent innumerable nights in local taverns; I spent many evenings in his home; and I even lived with his family for awhile. Here at UPJ [University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown] we were so close that for a long time, people spoke of us in the plural. “Bruce and Mike,” “Mike and Bruce.” “What are they up to?” Our late Division Chairman, Bob Hunter, once said to us that we were always “stirring up the pot.” Yes, indeed, we were, and many a tale could be told of our doings on campus.

But I don’t want to tell stories. A man’s life is a serious thing, and his death is more serious still. So I want to take the few minutes allotted to me to say why Bruce was important – to me personally, to UPJ, to the local community, and to the world at large. We all know that Bruce was a famously social person. He did not very much like to be alone. Once we went to an early Saturday morning breakfast at the old Topp’s Diner on Scalp Avenue. Bruce had been working in a coal mine in Barnesboro, doing fieldwork for his dissertation. His family was away, and he missed them. I am sure he did not want to go home to be alone in his big house in the Eighth Ward of town. So after breakfast, he looked at me and said, “What do you want to do now?” I was taken aback. I was used to being alone, and I went to my office every Saturday morning to work. I said, “Jeez, Bruce, I have lots of things to do. Maybe we can get together tonight.” I am sure he went home and called someone else.

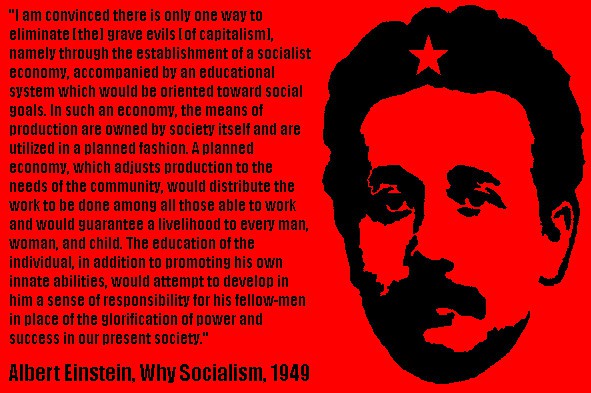

This event amused me and showed me that we were very different persons. But over the years I came to see that Bruce’s need to be with people was more than just his not wanting to be alone. Because if anything is true about Bruce, he was not an adherent of the creed of individualism held by so many people in this society. In fact, he believed, as do I, that such a philosophy is pernicious and the source of much that is wrong with us. What Bruce did believe was that each of us is born into and lives within a complex set of social relationships. We are, by our very nature, social beings, and this is to be embraced as the essential part of our humanity. It is the job of the social scientist to unravel the complexity of our social relationships, to comprehend them and lay them bare for us to see and comprehend in turn. This, I think, Bruce tried to do. What made him good at this was precisely his own sociableness. For it is not possible to grasp society unless you live and act in it, not as a distant observer but a full participant.

Now if a person lives fully in society and at the same time tries to uncover the mysteries of our social relationships, this is a fine thing and much to be commended. And if Bruce had done nothing more than this, he would deserve great praise. However, Bruce took things a step further, and this is where he really stands out. He came to see that our social relationships include a large number that are marked by a thoroughly repugnant inequality. He saw the worst of these in Africa – in Malawi, South Africa, Chad, and the Central African Republic. He saw many in the United States, among the Samoans in San Francisco, among the working people of Johnstown (especially in the Black community, which has experienced an outrageous racism), and yes, here at UPJ too. Of course, you might say, “Well, that is fine, but a lot of people know about inequality.” I might respond that a lot fewer people than one might think are aware of these things. What is even rarer, though, is a willingness to do something about it. Bruce not only understood the fundamental inequalities rooted deep within society, he also had the courage to struggle against them. He did what he could to help the downtrodden personally, as when he took Titchinonga Zishiri, from Zimbabwe, into his home and enrolled him at UPJ. More importantly he fought collectively with his friends and allies to see to it that justice was done, which in the end meant to participate in and lead the struggle against the powers that be. What I admired about Bruce was the fact that he was not afraid to stand up to those who had power and to fight to achieve some power for those who had little of it. For years now I have heard faculty say that they can not speak out until they get tenure. Well, Bruce helped to lead a union movement here when he was still an instructor.

The hardest thing in the world to do is to speak truth to power. Bruce did this early on and often. At UPJ, in the local community, and in the world at large, people like this are so badly needed. Bruce was such a person, and we have lost a great deal by his death.

I want to conclude with part of what is a sermon by the poet and minister John Donne. I think it captures, at least in part, Bruce’s spirit:

No man is an island, entire of itself;

every man is a piece of the Continent,

a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by

the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were,

as well as if a manor of thy friends or of thine own were;

any man’s death diminishes me, because I am

involved in mankind. And therefore never ask for

whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Played basketball with you and Bruce. Played rugby. Got stranded on route 30 with Bruce after rugby game. You gave me an opportunity to finish a college course. Much appreciated. World is really messed up. Been studying the Bible. Think it might have satisfying answers.