A recent article by New York Times journalist Neil Irwin finds that the housing market is still operating as a drag on the economy. While a few markets like New York City and San Francisco are booming and perhaps even reaching the “bubble” stage, most are not. One reason for this is the lower rate of household formation. “The number of households rose by an average of 569,000 a year from 2007 to 2013, according to census data, down from 1.35 million a year from 2001 to 2006.” When children leave their parents’ residence and move into an apartment or a newly purchased home, an additional household is created. If an adult child moves out of his or her own dwelling into someone else’s, a household is destroyed. Since the start of the Great Recession, children have become much more likely to either remain at home or move back. This is because young people, roughly between the ages of twenty and thirty-five, are suffering higher rates of unemployment than in the past, along with lower wages and less secure job tenure. They don’t see futures as bright as did previous generations. And as John Maynard Keynes taught us, pessimistic expectations about the future lead to lower expenditures on capital goods, and by extension big ticket consumer items like new homes.

A recent article by New York Times journalist Neil Irwin finds that the housing market is still operating as a drag on the economy. While a few markets like New York City and San Francisco are booming and perhaps even reaching the “bubble” stage, most are not. One reason for this is the lower rate of household formation. “The number of households rose by an average of 569,000 a year from 2007 to 2013, according to census data, down from 1.35 million a year from 2001 to 2006.” When children leave their parents’ residence and move into an apartment or a newly purchased home, an additional household is created. If an adult child moves out of his or her own dwelling into someone else’s, a household is destroyed. Since the start of the Great Recession, children have become much more likely to either remain at home or move back. This is because young people, roughly between the ages of twenty and thirty-five, are suffering higher rates of unemployment than in the past, along with lower wages and less secure job tenure. They don’t see futures as bright as did previous generations. And as John Maynard Keynes taught us, pessimistic expectations about the future lead to lower expenditures on capital goods, and by extension big ticket consumer items like new homes.

This is interesting because it explains one reason why economic recovery has been so slow; housing is an important generator of demand, and when it slumps or grows slowly, spending and employment tied to it follow suit. However, something else caught my attention in the Times piece. While new home building is still in the doldrums, the construction of apartments is not. Both younger families and retirees are deciding that renting an apartment is a better option than buying a house.

Building of rental multifamily properties, as the industry calls them—buildings with five or more housing units as part of one construction—was higher last year than it was even at the peak of the housing boom. Some 34 percent of all housing permits issued nationwide were for multifamily properties in 2012 and 2013, the highest since 1984.

From a societal perspective, this would seem to be a beneficial development. Apartment units are much cheaper to build than single-family homes; in the example from the article, they are less than half as expensive. Apartment buildings use less space than an equivalent number of individual houses. They can also allow families to economize and society to conserve energy, by, for example, providing central heating and air conditioning, laundry rooms, gyms, and pools. The enormous amounts of money spent on lawn care, including environmentally unfriendly chemical treatments, are eliminated. Apartments could be clustered around open spaces and convenient shopping facilities. The denser populations that they allow could also make for less alienated living, as residents could find socializing easier. Few things are more depressing than walking through suburban housing developments, with their oversized homes, enormous lawns, and no signs of life. No one outside, no children playing. Nothing. The feeling of loneliness is overwhelming.

It would appear obvious then that a future in which there are fewer single-family homes and more apartments is promising—economically, environmentally, and socially. Yet, Irwin fails to discuss this and instead focuses on the harm apartment building is doing to the recovery. For him, the lower construction costs of multiunit dwellings means less income generated and less employment. There are also fewer “spillover” effects from multiunit construction. All of the large mortgages, suburban lawn care, deck-building, fencing for the dogs, and endless spending on a hundred and one other projects mean more revenue for the banks, Home Depot, and every company that has tied its fortunes to the American Dream of owning a home. Things won’t get better, Irwin tells readers, until all of those potential households activate themselves and buy new single-family homes.

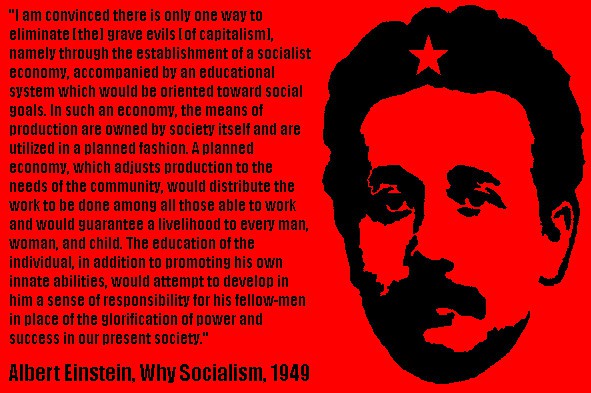

Here in sharp relief is the irrationality of capitalism. We must have rapid economic growth, which dictates maximum consumer demand. This, in turn, necessitates socially useless and environmentally harmful spending. In other words, this system requires waste. We could find ways to reduce expenditures on shelter, use energy more efficiently, and ensure that people live in clean and healthy circumstances, with maximum social interaction. We could guarantee that households can adequately survive without working long hours or going into debt. But we do not. In fact, we cannot. The logic of capitalism simply won’t allow it. And as this article strongly suggests, we can’t even imagine it.

Michael makes an important point here concerning the economic necessity of waste under capitalism – a point that we might want to keep in mind on the fiftieth anniversary of the appearance of the book, Monopoly Capital, by Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran. In that book, the provided extensive discussions of the role that waste plays in the absorption of the surplus that capitalist economies generate. In Marx’s terminology, surplus consumption plays a vital role in the realization of surplus value.

Jim, thanks for this. That the system requires waste and this waste absorbs surplus is something that escapes many leftists. You have writers like James Livingston arguing that the sales effort and high consumption are good things. That advertising is art. These are remarkably reactionary views, seeming only to justify the fact that some want their cake and eat it too. After them, the deluge. Also, the sales effort is now an important component of production itself, making it hard to separate necessary labor time from useless and labor time that does not generate surplus value but rather absorbs it.

But you miss one of the main reasons that people buy houses. Being a tenant is precarious. In most parts of the US, you can be forced to move on short notice just because or have your rent increased or be forced to give up your pets. It isn’t just because people are into lawn care, but that they want to know that they won’t be uprooted on someone else’s whim.