The troubles in the U.S. automobile industry have taken an interesting turn. In return for considerable concessions to Chrysler and General Motors, the United Auto Workers may become a majority shareholder in Chrysler and a large stakeholder in General Motors. The federal government will also own a large fraction of the shares of the two corporations, making both of them a lot less capitalist in their ownership structure than would have been imaginable only a few months ago.

Doug Henwood, on his lbo-talk email list, raised a critical question: what does ownership mean for the union? Or perhaps a better formulation: what could it mean for the union? Let’s look at this.

Like any organization, a union must have goals, and strategy and tactics aimed at realizing them. When capitalism was much younger and workers were beginning to understand it, the organizations of the working class—labor unions and political parties—had as their aim the abolition of the system of wage labor. This meant that they hoped to bring an end to capitalism itself, since wage labor is its lifeblood. It is through the ability of employers—an ability that rests on their ownership of society’s productive wealth—to compel workers to labor enough hours to produce an output which, when sold, will generate for employers a surplus over their costs that allows employers to make a profit.. This profit is the property of the owners, and they use it to expand their operations and their political and social power. If there is no wage labor, there is no capitalism.

There were good reasons for the working class movement to want to abolish wage labor. Here is how I summed it up in an article I wrote more than a decade ago:

Now, the whole thrust of capitalism is to alienate us from our humanity, to deny to us that which makes us human. We enter the workplace, having sold our labor power, our ability to create, to the capitalist, who considers it to be property, on a par with the other means of production. To the capitalist, we are costs of production, costs to be minimized whatever the human cost, which does not enter into the capitalist’s calculations at all. However, we are not happy to have sold our humanity, so we have to be forced to do the capitalist’s bidding. While this force is often enough effectuated violently, the true and perverted genius of capital is to accomplish it indirectly by reorganizing the labor process so that it is extraordinarily difficult for the workers to control it. [As Harry] Braverman shows us with wonderful clarity [in his book Labor and Monopoly Capital] . . .the essence of capitalist management is control, control over the labor process and therefore control over the worker. First, the workers are herded into factories, then they are watched and the divisions that they make in their own labors are turned against them through the detailed division of labor. Machines threaten them with redundance and further deskill their work. All of the piecemeal efforts at control are systematized by [Frederick]Taylor, who makes the separation of conception and execution the sine qua non of capitalist production. Both Taylorism and personnel management are reconceptualized again with lean production and its super-systematic hiring, just-in-time inventories, design for manufacture, team production, subcontracting, andon boards, and constant kaizening of the work. So careful have become the capitalist’s calculations that workers in modern automobile factories, places that autoworker, Ben Hamper, in his book, Rivethead, calls gulags, work as much as fifty-seven seconds of every minute, often for ten to twelve hours per day. The constant pressure to produce in circumstances in which the worker can exert virtually no control over the work, is what Braverman aptly describes as “a generalized social insanity.”

Labor unions and political organizations used a variety of tactics to implement their campaign to end the system of wage labor: mass strikes, boycotts, worker cooperatives, elections, and revolutionary struggle. For the most part, their efforts failed, although revolutions succeeded in a few countries, at least for awhile, and workers in other countries won significant social welfare programs that reduced the working class insecurity inherent in capitalism.

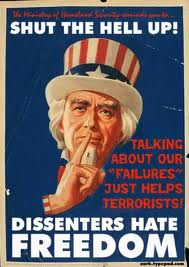

The main problem that unions and political parties faced was the hegemonic power of capitalism. Through control of the media, influence over what children learn in school (especially the relentless promotion of nationalism), domination of the government, and, of course, ownership of workplaces, employers were able to shape what workers think and wage a war of attrition against the workers’ organizations. In my book, In and Out of the Working Class, I put it this way:

. . . any organizations workers form to combat their oppression will find it difficult to avoid being influenced by the hegemony capitalism seeks to impose over society. It has been the rule rather than the exception that labor unions become bureaucratic and conservative, even if they were radical in the beginning. The labor movement in the United States, for example, was an active participant in the anti-worker Cold War, purging and persecuting its left-led unions and radical union leaders. Unions in the rich capitalist countries have actively supported the imperialism of their nation’s businesses and governments. Unions around the world have been sexist, racist, and homophobic, dividing workers just as surely as have the employers they fight against.

The U.S. labor movement achieved its greatest success during the Great Depression and the Second World War, when the workers in mass production industries, often led by communists and other radicals, built strong unions and established a formidable political presence. Good things might have happened—shorter hours, more control over corporate decisions, less alienating work, broadly progressive social programs won though political power, and so forth. However, the hegemonic power of capital proved too great. The UAW is a case in point. Here was a union built by radicals, one whose members occupied factories and defied police and courts, one that was the very model of a militant, progressive, and democratic union. Yet, after the war, when the union’s potential power was at its peak, a vicious leadership struggle occurred, pitting the liberal anticommunists, led by Walter Reuter, against the reds and independents. Reuther, like the ambitious future leaders of many other unions, red-baited his rivals—knowing full well that this would ingratiate him with both the corporations, the government (which, for all practical purposes had made being a red illegal), and conservative unions, and put the reds in real jeopardy—and defeated them.

Soon after taking power, the Reutherites signed the “Treaty of Detroit,” a long-term contract with General Motors that gave the workers considerable wage gains, but conceded the management of the corporation to the bosses. What this meant, in effect, was that the union agreed to confine bargaining to the terrain of the labor market, demanding only that the companies pay a high price for the labor the workers had to sell. There were work rules, of course, and a worker who thought these were being violated by the company could file a grievance, which wold be handled by a union staff person, often with little input from the aggrieved member.. But the nature of the product, how the cars were produced, the speed of the assembly line, the prices of the automobiles, and most importantly, the nature of the work that the employees performed, were all off limits in the bargaining, the sole prerogative of the employer. So, the mechanisms of control described in the first quote above were beyond the reach of the union. Whatever human qualities the work had were stripped away to enhance managerial control, and whatever human qualities the work might have been made to have were not even considered. This not only alienated the workers along the never-ending assembly line, but it also denied them any chance to develop their capacities to run the industrial machine themselves.

In addition, the many fringe benefits, such as health care, vacations, holidays, and pensions, were won by bargaining with individual companies. This tied essential aspects of worker security to the ability of the corporations to pay for these things, and it divorced the union from any social movement that would demand the collective provision of such security. Once this was done, it was a short step for the UAW to embrace labor-management cooperation; it was argued that this would allow the companies to compete effectively with their international rivals, especially the Japanese automobile manufacturers, which, supposdedly, were more efficient because of such cooperation. [Another probable reason for the union’s rush to cooperate was the fact that the union’s internal political structure had come more and more to mirror that of the companies. The UAW became a “one-party state,” where rank-and-file dissent was not tolerated.] Once a “we’re all in the same boat” mentality came to be internalized by the union’s leadership, it was an even shorter step for the UAW to accept concessions when the companies claimed economic distress. The union said that concessions were necessary to guarantee jobs, but as Sam Gindin, former chief economist for the Canadian Auto Workers, argues,

At the end of the 1970s, when the first round of concession bargaining began in the US, the UAW had 450,000 members at GM. Today, after repeated contracts that allegedly “won” job security in exchange for workplace, wage, or benefit concessions — sold by the union as well as the companies — the UAW’s GM membership is down to 64,000. If GM is “successful” in it is current restructuring, that will be further reduced to 40,000. Thirty years of concessions and a 90% loss in jobs. If ever there was a failing strategy for workers, this was it.

He also says that,

The greatest danger for workers is that the acceptance of concessions represents not just a temporary setback, but also a more permanent defeat. To the extent that concessions lower expectations, undercut arguments for why others should join a union, and risk the erosion of worker confidence in collective action, workers and their unions move into the future disoriented and weakened.

Let me add that one of the concessions the UAW had made is that new hires get about one-half the pay of more senior workers, for doing exactly the same work. Could there be a more anti-union thing to do? How can there be solidarity in such a circumstance?

What developed in the U.S. automobile industry was a union that confined its bargaining to labor market issues, abandoned efforts to confront managerial power inside the plants, became dependent on the profits of individual employers to fund its wage and benefit gains, including some protection for workers from income loss when plants closed or layoffs occurred, embraced labor-management cooperation as a principle and not simply as a temporary tactic, and was easily convinced that concessions were needed when their presumed adversaries declared that they were. The focus of the union became increasingly short-term and “pragmatic.” No long-term strategy was voiced, much less acted upon.

The UAW’s trajectory was rejected by its Canadian members in the mid-1980s, leading to their breakaway and the formation of the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW). The CAW rejected concessions, and over its first decade engaged in direct action tactics such as plant occupations to further its demands. It developed a radical education program for members and shifted to the left politically, demanding larger public investments, with public controls, that would benefit workers and their communities. It allied itself with progressive forces in Canada and tried to end the isolation that the privileged sectors of the work force had brought upon themselves by the policies described above. Unfortunately, in the last few years, the CAW has become more like the UAW, even giving concessions to General Motors at plants where costs were competitive and productivity and output quality very high.

The last round of concessions, brought to the table by corporations on life support (billions of dollars from governments, which are themselves demanding that the workers take pay, benefit, and employment cuts) because of the economic crisis and decades of poor management, are only the culmination of a long history of union capitulation and strictly defensive struggle.

This brings us back to our original question. What might it mean if the union becomes a major shareholder? It could mean a lot. The union could use its ownership to make demands that things change. It could put the corporations on record as favoring national, single-payer health care. It could demand that the corporations actively fight for this too. It could develop a set of principles concerning the restructuring of the automobile industry, so that idle plants are retooled or restructured for other kinds of production (green production for example). It could make the companies, in effect, public trusts and push for maximum community control over how they are run and what they make. Again quoting Sam Gindin:

If we are serious about incorporating environmental needs into the economy, this means changing everything about how we produce and consume and how we travel and live. The potential work to be done in this regard — in the tool and die hops that are closing, the component plants that have the capacity to make more than a specific component, and by a workforce anxious to do useful work — is limitless.

The equipment and skills can be used to not only build different cars, and different car components, but to expand public transit and develop new transportation systems. They can participate in altering, in line with environmental demands, the machinery in every workplace and the motors that run the machinery. They can be applied to new systems of production that recycle used materials and final products (such as cars). Homes will have to be retrofitted and appliances modified. The use of solar panels and wind turbines will spread, new electricity grids will have to be developed, and urban infrastructure will have to be reinvented to accommodate the changes in transportation and energy use.

What better time to launch such a project than now, in the face of having to overcome both the immediate economic crisis and the looming environmental crisis? And what greater opportunity to insist that we cannot lose valuable facilities and equipment, nor squander the creativity, knowledge, and abilities of engineers, skilled trades, and production workers?

A cynic might say to all of this: “coulda, woulda, shoulda.” And as far as the UAW is concerned, the cynic would be right. The union gives us absolutely no reason to believe that it will suddenly become the leader of national progressive forces if it becomes a majority or powerful minority owner of two automobile corporations. Because if this is its plan, why hasn’t it done what it could have done all along? Why didn’t it take a different course of action when it could have, many years ago? Why hasn’t it had it members in the streets, in the tens of thousands, making demands now? The truth is that the UAW has no vision, and it appears incapable of developing one now. The CAW may be different. It still has radical cadre, and what it has done in the past could now allow it to mobilize mass actions to make changes. In the United States, however, rank-and-file workers will have to try to build alliances with other workers, with communities, and with any other progressive forces out there, to force the union to begin to act positively and offensively, in the interests of all workers, to begin the long, slow, and arduous process of challenging a system that cannot possibly serve the interests of the vast majority of people.

Hey! I’m an organizer with UNITEHERE on the Hotel Workers Rising campaign in Indianapolis, IN. Indianapolis hotel workers are engaged in a struggle of historic proportions. There are currently no union hotels in America’s 12th largest city, yet huge majorities of workers at the Sheraton, Westin, and Hyatt Regency hotels have demanded a card-check neutrality agreement. They have yet to hear back from the hotel owners. Work conditions in Indianapolis hotels are really tough. Housekeepers routinely clean up to 30 rooms per day and make just $7.25/hr. We’ve just put together an inspirational video documenting this 2-year struggle. It would be great if you could put it up on your blog for people to watch. Thank you,

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=exBtVnZaWUk