The writer William Burroughs made the theme of “control” central to his work. He spent most of his life obsessed with the idea that he was under the insidious control of outside forces, and by extension, so were we all. His life can be seen as a quest to free himself from control: through drugs, through Scientology, and, most of all, through writing. There is no doubt that one reason why his works resonate with readers is that Burroughs was on to something important. Unfortunately, however, his diagnosis of the source of control was badly mistaken. Like the American libertarian he was, Burroughs believed that it was the government, which to him represented the forces of collectivization out to subordinate the free individual, that was trying to control us. Thus he was repelled by the socialism of the Soviet Union and even the social democracy of the Scandinavian countries. He feared that the more government there was, the closer we were to the kind of total control represented by fascism. [I might add that Burroughs’s obsession with the individual seems to have translated into an egotism that denied any social responsibility. He was a crack shot, yet he killed his wife with a pistol while playing a “William Tell” game and with a weapon he knew had an inaccurate sight. Then he quickly abandoned his son Billy, who was raised by Burroughs’s parents in Florida. Billy soon enough took to drugs and alcohol, but his father showed little concern. When Burroughs brought a teenage Billy to Tangier, the poor boy was constantly harassed by Burroughs’s gay companions for sex. Ultimately Billy had to have a liver transplant, one of the first performed by the legendary surgeon Thomas Starzl. The new lease on life soon gave way to old habits, and Billy destroyed the new liver as well. He died still a young man. Maybe fatherly concern and love would not have helped the son, but we will never know.]

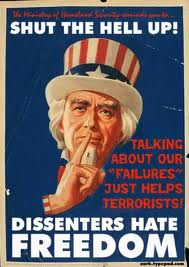

There is good reason to fear the government. Modern states, especially the United States, with its vast military apparatus, have an immense capacity to ruin any individual’s life. Should the U.S. government want me to disappear, I have no doubt that it could easily make this happen. And the U.S.S.R.’s government put dissidents in prisons, mental hospitals, or a grave. But what Burroughs failed to grasp, at least in the case of the United States and all other countries organized economically like it, was that it is the organization of the economy in a capitalist form that is the fountainhead of the control exerted over us and which is the source of our foreboding, our alienation. What makes us human is our self-conscious interaction with non-human nature and with other people who are, of course, a part of nature, as we go about producing that which satisfies our needs and dreams. This production, or work, is fundamental to our being and is the source of our remarkably complex social organization. Our understanding of what we are doing, our grasp that we alone can reshape the world around us and imagine ever more diverse and sophisticated productive activity, gives us not just food, but our art, literature, and science.

Burroughs was lucky to be able to create his art, though he struggled mightily to do so, because in creation he was acting like a full human being. Most people, however, are not so fortunate. In contemporary society, human consciousness and activity have made it possible to produce enough output for every person to live in material comfort and also have enough time to develop his and her creativity as fully as possible. Yet, those few who control most of the world’s productive forces secured this control and maintain it by systematically denying it to everyone else. And in the process, they thoroughly stifle our capacities.

The most basic source of their control is their monopoly of access to employment, which means essentially access to the property of others. Here capitalism is far worse than gathering and hunting or feudalism. So called primitive peoples naturally combine themselves with the world around them to produce the means of their own existence, and even serfs had the right to use part of the land of the estate. Today there is no right to use the land or tools or machines and buildings unless you own them; otherwise you have to depend on the willingness of some employer to hire you. It is incredible that in societies capable of producing goods in abundance, people have no guarantee whatsoever that they will get any part of the output or be able to develop and use their skills. Once employment is secured, control over our capacity to labor is owned by the employer; our labor power is the employer’s property. We have no right to work as we see fit; if the way we work is not pleasing to the employer, we can be fired. There are myriad ways in which employers tighten the screws at work: they herd us into factories, the better to observe us and make sure our noses are to their grindstones; they take our skilled labor and divide it into details or subtasks, making it easier to replace us and harder for us to grasp the totality of the entire work process; they study us with clocks and cameras, devising the “optimum” way in which each subtask is to be done and compelling us to work in exactly this way; they devise diabolical techniques to make us work harder, such as speeding up the assembly line, cutting the size of work crews or teams, and reducing the materials available to us, but expecting us to maintain the level of production (and publicly humiliating is if we do not); they invent ingenious carrots and sticks to habituate us to the whole system of robbing us of both the output we produce and our dignity. Many volumes have been written about these “control” mechanisms. Suffice it to say here that, while employers do not always succeed in implementing them and workers often resist, it is inevitable that the bosses will try mightily to make work as machine-like as possible and their “hands” appendages to those machines. The result is, as Adam Smith put it (with no grasp of the fact that he was describing labor in capitalism rather than labor in general), work requires the laborer to give up “his tranquility, his freedom, and his happiness.”

Employers have spread their tentacles outward from workplaces to the larger society—to the government, to the schools, to the media, toward every aspect of social and cultural life. They try to pressure other social spheres, through the power that their wealth and control over society’s productive forces gives them, to enhance the domination over the labor that is the ultimate source of this wealth and power. Today, when the organized strength of working people is weak, employers have come to all but operate the government. President Obama has already caved in to corporate pressure in opposition to the Employee Free Choice Act and national health care, and his economic recovery program has put working men and women at the back of the line. For all practical purposes, Goldman Sachs and its brethren are running the country. And Obama was supposed to be a friend of the working class. The nation’s schools, responding with typical cowardice to the No Child Left Behind law, have made the schools even more craven to their corporate masters than one would have thought possible. How anyone comes out of our public schools (much less our private religious schools or home schooling) with any capacity to think critically is a mystery to me. Economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis showed long ago in their classic account of U.S. education, Schooling in Capitalist America, that the student traits that were rewarded with good grades were perseverance, obedience, punctuality, identification with school, and similar virtues, which turned out to be exactly the same characteristics used by employers to reward employees. With schools teaching to the test, operating classrooms as if they were business enterprises, and thinking of students as consumers, is it possible to imagine that the traits Bowles and Gintis found negatively correlated to grades—creativity, independence, and aggressiveness—have suddenly found favor with teachers? As for the media, the ways in which we are controlled and the reason why do not often find their way

into our newspapers, television newsrooms, magazines, and movies. A discussion of the police-state quality of many of our workplaces is less likely than the suggestion that space aliens have secretly infiltrated our brains.

One consequence of the absence of freedom at work is that workers seek freedom elsewhere. For the vast majority, this is a futile search because the grotesque material poverty that they suffer precludes much enjoyment of any kind. For the rest, it has become increasingly difficult to be free of the market and wage labor outside the sphere of direct employment. Every nook and cranny of family and community life have been invaded by the market and made subservient to it. We are left only with the impersonal buying of consumer goods, which has implicitly become the sole purpose of life itself. As the late capitalist Malcolm Forbes put it, “whoever dies with the most toys wins.” Forbes was one of those in control, however, so easy for him to say this. And he doesn’t mention that we are every bit as controlled as consumers as we are as workers. Mass marketing has achieved a level of sophistication so great that most of us don’t even know that we are being manipulated.

Our experiences in our workplaces, in schools, with the government, with the media, as consumers, and with almost every other institution with which we come in contact, help to shape our thought processes in such a way that we behave most of the time in ways that reinforce the control that employers need if they are to make money. Of course, there is the usually invisible threat of violence lurking in the background in case more subtle measures fail to elicit the desired behavior. But ordinarily these are unnecessary. People have become so habituated to workplace control that they think of it as normal. In the work “team” pioneered by Japanese automobile companies, team members have, at management’s request and insistence that this would somehow empower them, actually time-studied one another, knowing full well that time studies mean only two things: fewer workers and more intense labor. Consumers seldom complain no matter how shoddy the product or how bad their treatment. A student of mine once said to a friend, in reaction to something I said in class that the student know to be true, “I can’t believe what Mike said,” meaning that it was more comfortable for him to believe what wasn’t true. Students would take down whatever I said and never ask a question, good preparation for mindlessly doing what their bosses tell them to do.

How can this control be combated and finally vanquished? If we say, as I believe to be the case, that only an organized working class has any chance of success, we have to realize the daunting nature of the task at hand. The system of control is extraordinarily powerful, so much so that the workers’ own organizations, the labor unions, have come to resemble to a frightening degree the corporations against which they are supposed to be fighting. The most discussed labor leader in the United States, Andrew Stern of the Service Employees International Union, has structured his union along strictly corporate lines, right out of instructions from the management theoreticians who write for the Harvard Business Review. He thinks not in terms of an energized, empowered, and class-conscious rank-and-file but in terms of dues units, union density, and adding value for employers. He sees members the way Frederick Taylor saw workers: as means to a corporate end but not as an end in themselves; they are to be controlled so that the union can get larger and Stern and company more powerful. Karl Marx said that the capitalists, by taking actions that would ultimately intensify class struggle, were digging their own graves. This may be true. But when you see working people blaming immigrants for their difficulties; when you see working people not understanding that Medicare is a government program; when you see working class parents sending their children off to kill Iraqis and, in the case of reservists, going themselves; it is hard not to think, when you are feeling hopeless and the optimism of the will gives way to the pessimism of the intellect, that workers are busy making coffins—for themselves.

That’s certainly thought provoking. In my youth I was inspired by Bowles & Gintis. However in another post maybe you ought to look more at the contradictions in this control process. Most research shows that it’s a myth to think that such absolute control really exists. If people submit to such control, it is primarily because there is some kind of pay-off if they do, and because they cannot easily envisage or realize a better alternative. But this says nothing yet about their subjective attitude to the controls of which they are aware. Markets and workplaces in fact cannot function at all without a great deal of (unpaid, non-market) voluntary cooperation and assent, going far beyond what you can in fact control, and markets and workplaces break down without it. It is just that the modalities of cooperation become a mystery owned by management science, dividing people into organisers and organized. Even at the deepest levels of alienation, we do have choices, including about the meanings we attach to, and convey, by our own actions. We don’t have to live in Skinner boxes, because we can learn to understand the way out. Thus, most experienced radicals I know of say, that if you want to equip people with the power to change their world, the place to start is by making them more aware and confident about the liberties they do actually have, and getting them to do something themselves in favour of their own lifechances, so they win something, anything. Self-organisation starts with human organs. Even in a very oppressive situation, you still have some choices you can make in what you do and don’t do. In military science, moreover, one thing you learn is, that if you want to defeat the enemy, you should never endow the enemy with an aura of more power than he really has, but, to the contrary, focus on his weakness and lack of credibility. If you make the enemy much bigger than he really is, that gets in the way of defeating him. In Judo, you learn that you can defeat the opponent with his own strength, not by clashing with it directly, but by catching him off-balance because in asserting his strength he imperils his balance. It’s like, “the emperor has no clothes”. If the Left suffers from bipolar moodswings of optimism and pessimism, that’s just because, being reactive, they don’t know what actually causes the optimism and pessimism, confusing object and subject. In the words of Engels, “Ideology is a process accomplished by the so-called thinker consciously, it is true, but with a false consciousness. The real motive forces impelling him remain unknown to him; otherwise it simply would not be an ideological process. Hence he imagines false or seeming motive forces”. You cannot solve the problem of control, or any other problem, until you can frame the terms of the problem correctly and honestly. And pessimism is mainly the emotional result of framing the problem incorrectly for whatever reason, so that it cannot be solved. Psychological science shows that in exactly the same situation, one person is optimistic, another pessimistic, which indicates that there is nothing intrinsic to the situation itself that would stimulate optimism or pessimism, but rather that it depends on how it is subjectively perceived, and what attitude one takes on this. You have a choice about whether to be pessimistic or optimistic. It is the ultimate reification, to suggest that you don’t have that choice, and it has the result that you deny your own nature. “Real Marxism”, in which the active human Subject occupies centre stage, instead of immutable objective laws of history, begins with the consciousness of freedom, and the rejection of the reification of “control”. It’s your choice…

Jurriaan,

Thanks for another thoughtful post. I looked at things one-sidedly here, it is true. Probably to be thought-provoking. I have in other things I have written looked at the contradictions in this process. I used to teach collective bargaining, and a basic principle is that it is never the case that a party to the bargaining has no power. It is just a question of finding out what that power is and using it. I do, however, think that Marx didn’t foresee just how powerful the modern state and corporation are. That is why it is so exasperating to see labor leaders refusing to try to build real working class power, in part, as you say, by focusing on your employers’ weakness and lack of credibility. They won’t use the power they do have and could develop. They won’t operate on the assumption that strong opposition to capitalism or at least its worst aspects is a normal way of thinking and acting.

Well actually I appreciate your work very much, it’s a real achievement and that is why I wondered why you wrote like this. Are you feeling somber?

Did Marx really fail to foresee just how powerful the modern state and corporation are? I am not so sure. It is true that in his day, the state’s tax take and expenditure represented no more than 5-10% of the national income. But on the other hand, the population to be controlled by the state was vastly smaller, and there were fewer civil rights. Marx was well aware of Thomas Hobbes and of the Prussian state bureaucracy, and he was himself expelled successively from Germany, France and Belgium by the state authorities. If he did not directly attack the state much in his criticism, there was a very good reason for it, since he knew from experience that it could mean that he (and, in England, his family) could be expelled from the country where he lived. In other words, he was a known “dangerous radical” constantly under the watchful eye of the state authorities.

In my experience, many union organisers are sentimentally anti-capitalist, but in practice the main ethical issue in their work (insofar as they are workers’ advocates) is whether you can win a good “compromise” between Labour and Capital, or have to consent to a rotten one. In turn, however, this concern is shaped by perceptions of what can be realistically achieved at the time, and there your criticism has some force, insofar as you may be able to prove, that much more could be achieved with a less conservative outlook.

In the history of capitalism, there have been rather few explicitly anti-capitalist unions, and with few exceptions, their militancy (1) was fired by Left parties of one stripe or another, or what amounted to political parties; or (2)they were driven to anti-capitalist agitation because society was actually disintegrating. In the main, unions have been “defensive” organisations of the workers. There is a gigantic distance between a student launching a hot-air anti-capitalist slogan he learnt from reading a book, and a union organiser negotiating pay & conditions, who is personally responsible for representing many workers about things that matter most to them in their lives. I know this for a fact, because I and a close friend crossed that distance in our lives once. To be a good unionist, you aren’t “anti-capitalist” so much, as “pro-worker”. But in fact most workers aren’t anti-capitalist in normal times, and thus, anti-capitalist rhetorics will only alienate them (well, it depends a bit what you mean). For their part, most “Marxists” I have known hated the working class in practical life.

In my experience, many union organisers are hostile to radical Leftists not because of their ideals, but because these people have no idea about how to relate, how to communicate or what is really at stake, and they vent all kinds of radical ideas at every opportunity without any idea of what the consequences of that are for real people. Moreover these radical Leftists have a consistent habit of calling into question and decrying the sincerity of the motivation of other people, and they play the silliest and dumbest games of “I am more correct and radical than thou”. In addition, the radical Leftists have a really warped idea of the relationship between theory and practice – they believe for example that the task of the party is to propagate Marxism – and in the matter of organising they get even the very simplest, tiniest basics of organisation wrong, with disastrous results. In other words, you are dealing with a large number of people whose radicality grew out of their own social, sexual and cultural maladjustment, but unfortunately the reality is that you cannot build any serious organisation out of socially maladjusted people, you can build it only with people who have a real life of their own and sources of satisfaction independent of politics. But if they have a real life of their own, you also have to have a due regard for it, rather than contemptuously sneering at it as many radical Leftists are prone to do.

We inherited a Leftist hippy and punk culture of struggle from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, but in fact – whatever its merits – much of that culture makes no sense anymore now, and to adhere to it still, is in reality totally conservative – at best it amounts to the preservation of an ideal of struggle, with the belief that if you waft these images of the past at people formed by a different generation, that it will interpellate them. But this misunderstands even the uses of tradition. The main feeling I get about the US Left is that they complain that reality fails to measure up to their ideal, and they feel frustrated about that. But this is a loser’s game, and that is why radicals who aim for success, and aim to do what you need to do to get success, avoid this Leftist culture like the plague, because it only drags you down and embroils you in useless disputes which only waste time, energy and money. If you want sympathy for your cause, best to go to people who can really advance it, rather than “groupies” who really haven’t got a clue and misrepresent their own motivations to themselves.

Correct me if I am wrong.

Joshua Cohen posted a link the the latest from the admirable Noam Chomsky http://www.bostonreview.net/BR34.5/chomsky.php

I’ll crosspost it here for you because I think there’s an important point to be made here relevant to what we were saying:

Chomsky talks sadly and solemnly of the marginalization and atomization of the public who are mere “spectators of action” but that’s just a matter where you care to focus your attention. Okay, if you want to be sucked in by the media, go for it. In reality, the public is very active, it’s just that the Left doesn’t like what they do. But that’s not a very good basis for getting on with the public. If you want to sway the public, but you reject what they do, it’s not exactly going to be a success formula. You have to start off with what people are doing really well, and if you cannot see that, you’ll never be a man of the people. How e.g. did Mr Obama become president? He gave them hope. How? By affirming things that they really value. The Left whinges about how people don’t have any power, but they miss by a mile the power that they really do have. No wonder that a democratic breakthrough of the people becomes a mystery!

Jurriaan said:

“But in fact most workers aren’t anti-capitalist in normal times, and thus, anti-capitalist rhetorics will only alienate them”

and

“In reality, the public is very active, it’s just that the Left doesn’t like what they do. But that’s not a very good basis for getting on with the public. If you want to sway the public, but you reject what they do, it’s not exactly going to be a success formula. You have to start off with what people are doing really well, and if you cannot see that, you’ll never be a man of the people. How e.g. did Mr Obama become president? He gave them hope. How? By affirming things that they really value. The Left whinges about how people don’t have any power, but they miss by a mile the power that they really do have. No wonder that a democratic breakthrough of the people becomes a mystery!”

I’ve read this exchange with some interest, but there are some points that you bring up, Jurriaan, that have made me a bit curious. I was hoping you might clarify some.

I agree somewhat with your characterization of “leftists” (partially caricaturized though it looks) as being too ernest in their work trying to radicalize (other) workers, but this and the quotes I copied above lead me to wonder what is to be done then? I get the impression from your words that critique of the working class itself is out, that it has nothing much to learn from scholastic types eg students of Marxism. I also find myself wondering just what the American working class is doing “really well” that garners such enthusiastic support from you. As for your invoking Obama as an examplar, don’t you think that the “hope” he gave people (never minding those sections of the working class who, wrongly, voted in Bush twice) was in fact ultimately hollow rhetoric, saying things people want to hear, done not only as a rep of the somewhat more humane side of US capitalism but also as a well-off, upper middle-class man who hates conflict and struggle?

I’m reminded somewhat of the feeling I got after reading sections of Hardt & Negri’s Empire: there’s some real enthusiasm that’s refreshing to read, but it seems so taken by surfaces and appearances that I’m left wondering what the argument’s about.

(Sorry about channeling Doug Henwood so blatantly, Mike; blame him for getting me started thinking along these lines.)

Thanks for the second comment and the crosspost. I think the notion of control is useful in that it gives me a way to organize an analysis of capitalism and class struggle. And it has the virtue of being directly connected to every worker’s actual experiences. When I teach, I use it to discuss the two-sided nature of control, pointing out the weaknesses of capital that derive from its attempts to attain control.

I avoid most of the left like the plague and seldom participate in discussions. If they have engaged workers, then I am willing to talk about my own experiences as a labor educator, etc. In my worker classes, I try to empower the students by drawing out of them knowledge that already shows that they do grasp a lot of economics and gettign tehm to think beyond the day to day struggles they all must engage in as union leaders.

Michael Lebowitz is doing good work in writing about how to build socialism now. From what you have said above, I think you would like him.

What the argument is about, is whether you view people as being powerless subjects who suffer monumental domination and control “from above”, or whether you see them as active subjects who have all kinds of powers to influence what happens and to change things, even despite that control insofar as it is real.

Marxists get frustrated because the working class isn’t rising to its historic mission of overthrowing capitalism, and then they conclude the workers are “backward”, stupid etc. and that they must be educated by the Marxists. This has nothing to do with Marx actually, the Marx who said “the educators must be educated themselves”, referring to a process of self-change which combines with the attempt to change social conditions, constantly learning from others, with a spirit of genuine curiosity about human affairs.

In reality, workers are producing the goods and services that people need to survive and prosper, raising families, caring for people, making friends, tackling life’s challenges. In other words they are human beings, often highly skilled human beings, with extraordinary pursuits, hobbies, interests, capacities. If you are not interested in people and their lives, and if you focus on people who are just bitching about life, this is hardly a recipe for success.

This is not to romanticize our lives as workers, or denying the need for social criticism, but just saying that you have a choice in who you associate with, and you have a choice in whether you are focusing on what people are achieving in daily life or or whether you are focusing on everything that’s going wrong. Ultimately all progressive change is initiated and achieved by constructive people. I spent ten years at university, reading the literature, learning and teaching, and about twenty years in the workforce, doing all kinds of jobs in two countries, and that shaped my outlook, relativising the academic ideas in the light of practical experience. And I can tell you now, we workers aren’t backward like the Marxists say, and we are educating ourselves all the time, even when there is preciously little time in between all the other things you have to do to keep life going.

I am not passing judgement on what Mr Obama did, I am merely saying let’s look at what he did to achieve political success and how he did it – is there something to be learnt from that about the shape of popular consciousness? And I think you can learn from that. At least I do.

Toni Negri and Michael Hardt may be good people but I am not a fan of their work, it’s an intellectual perverse, postmodernist rococo impossible for normal people to follow, and in fact they get all the main issues wrong in my view. I am a fan of Michael Yates, who writes and teaches clearly, in a way genuinely useful to people who do not have a Phd in philosophy.

I do not have the luxury of whinging philosophically about everything going wrong and publishing about that, because I have plenty real problems to solve and knowledge I really need to obtain. It’s not an academic issue for me that I can just shelve when I feel like it. The whingers are just an obstacle for me. When like today workmates said I was doing something well, that does me good. And you need that support because otherwise you just don’t survive. Todd proves this himself, by focusing on “enthusiasm” and indicating his need to believe in something, hoping it is not “superficial”.

Of course any successful political or personal engagement is going to be impossible, if you deny practically every basic requirement for its success!

First, as a Marxist, I take some affront at this characterization of people like me as simply automatically seeing workers as stupid because “they just don’t get it”. I have no doubt that there are Marxists who have this thought in their heads just as I know from personal experience that there are those who don’t. I learned from reading other Marxists (and non-Marxists) how prevalent this attitude is and some material for combatting it, in myself and others; I’m sure others can and will learn as I did.

As for how I view the working class, I’d say all of the above. Pressures to conform and “stay with the program” are present everywhere (and not just because we live in class societies; I suspect, as social animals, that there’s at least some hard-wiring that makes it more difficult to stand out in a group), but there are also plenty of areas of contestation and places where bourgeois society hasn’t really insinuated itself very well (if at all) into working-class consciousness AFAICT.

I completely agree with Marx’s quote about the educators needing education; life changes and our education has to change to suit its circumstances. But he also published his Manifesto and first volume of Capital in the hopes that the working class would read it, think about it, and make good use of it (adding that such use can’t come by way of a “royal road” to knowledge). In short, the education of the working class and their organization into a conscious proletariat is something that cannot be ignored.

Workers do indeed take part in those facets of human life that you mentioned above but so do capitalists and their functionaries and representatives. I was left with the impression from your words that workers did something _as workers_ that was unique to them as opposed to something that humans as such do. I see I was mistaken.

What you said about choice above is a bit confusing. I’m not entirely sure what you’re talking about when you say that we can either focus on everything going wrong or “what people are achieving in daily life”. When I read your words on the latter, I immediately think about the daily reproduction of life, which is interesting enough and goes on regardless of what Capital thinks about it (even though Capital has to have a hand in it), but I don’t see why focussing on that is so important. As for the former point, when Marxists focus on “everything going wrong”, I see that as examining why things do or don’t happen in class society or what can be done in terms of winning the class war (or at least putting us in a better position vis-a-vis the owners). Dismissing it as pessimistic seems a little premature, to put it mildly.

Re. Obama: “is there something to be learnt from that about the shape of popular consciousness?” Well, yes, but I don’t think it’s some great mystery to be anxiously pored over as terribly important. The man lied and still does so, certainly as a member of his class and quite likely because (I suspect) he fetishizes co-operation and social peace.

“When like today workmates said I was doing something well, that does me good.”

Yes. Same for me. But what point are you trying to make with this?

“Todd proves this himself, by focusing on ‘enthusiasm’ and indicating his need to believe in something, hoping it is not ‘superficial’.”

While Todd is happy that Jurriaan finds something worthwhile in what Todd wrote, Todd is still having trouble with what Jurriaan wrote and is still feeling confused (especially when Todd is addressed in the third-person as if he weren’t around).

Thanks, Todd and Jurriaan for a good exchange. I used to be hassled all the time when I was a college teacher by members of various left groups. One in particular, called then the Revolutionary Communist Party was always after me. I knew a few members, who lived nearby. Two had gone to work in a coal mine, to “bore from within,” looking I suppose for recruits among “real” workers. Many members of my extended family were miners. I was born in a company town, in a mining company shack. I asked the new miners if they challenged their mining brothers if the miners exhibited racism, something that my relatives did often enough. They said, oh no, we couldn’t do that. I said, well how do you ever expect to bring about change. How can the miners ever begin to think about their racism if you don’t challenge it. Here is a good example of leftists not respecting workers and imagining that they might change or even trying to find the roots of their thinking, which may not be as hopeless as we might think. Maybe had the supposed communists talked about the racial solidarity shown by miners and their union, they could have made some real headway.

Mike said:

“Here is a good example of leftists not respecting workers and imagining that they might change or even trying to find the roots of their thinking, which may not be as hopeless as we might think.”

Yes, I remember some people writing about that sort of thing on LBO-Talk. Doug’s answer was simple common sense: why can’t we talk anti-capitalism and anti-racism at the same time? It’s not like there’s some objective reason for prioritizing one over the other.

When I was involved in the drive here at Algonquin College to unionize the part-timers (the provos only recently made it legal), I attended a meeting of the organizing committee during which some members brought up a recent OPSEU shin-dig where a couple of gay members attended (I think) wearing something pretty flamboyant if not outright threatening to masculinity (maybe dresses; I don’t recall now). One member, a woman, was openly disgusted that such people would dare attend and act that way. When I asked her what was wrong with it, all she could really do was bluster and mutter about “obviousness”.

I am not really sure why the concept of the free choices that people have should be confusing. I suppose that many Marxists think that choice is a bourgeois ideology which flatly contradicts the oppression of lack of choice among those who languish in a hell of exploitation and oppression, but that simply isn’t true, it’s a deformed idea. Almost anyone can make some free choices, most primally, about the meanings they attach to their own activity, and this is precisely the starting point of getting yourself out of an oppressive hell if you are in one.

The theoretical question really is this: how can you expect people, who cannot even get on top of the problems of daily life, to assume collective control over the management of society’s resources, the great vision or dream that leftwingers have? How can people, who have difficulty exercising responsibility in daily life over the concerns that affect their lives, be expected to exercise responsibility for much bigger decisions affecting many people? How can people participate in political activity when they already have difficulty in negotiating problems in their own social life? Well if you want to generate real and mature answers to this kind of problem, then I think you should be at least interested in how people are actually living their lives, and think of ways that would make a positive difference to their lives, not in some distant future but now. And I think you cannot really do that “from the outside”, let alone from a Marxist throne, but in the course of actually relating and participating in life yourself.

Obviously you are in no position to “take charge” or “take control” of your own life situation if, for one reason or another, you don’t even believe that you have any choices or options there. I can vouch for that, because I have had plenty experience with that sort of problem, I mean my life wasn’t all plain sailing by any means. And so, I think, that a prerequisite for a political engagement is a kind of culture which actually facilitates the process of people exercising their freedoms and getting more control over their own lives and lifeworld. That is the prequisite for a healthy politics which can withstand the dirty games that can and will be played. But this sort of thing is far removed from Marxists believing that they have to bang the authorative Marxist ideology or progressive liberal moralisms into people’s heads. It is not a question of trotting out endless propaganda about what some authority has said, but using your own nouse and creativity to apply a theoretical perspective to a real situation, with genuine empathy for others. If you are just merely the hack of an authority, you kill your own creativity. I mean, I participate in some scholarly discussions about Marx, but I wouldn’t say it is the “be all and end all of life”, far from it, at most I can hope to do my bit to unlock Marx from the strangulation of Marxist ideology.

I would be very reluctant to accuse Mr Obama of lying, unless I had irrefutable proof, and even if I had it, the question is whether if I accused him of lying would have any positive effect in the given context. In principle, I think I should not “accuse” but “prove”. I’m very aware in this that Mr Obama has taken on an enormous responsibility in which he somehow has to reconcile a vast number of different interests. It becomes enormously difficult to remain consistent in that. And should I have difficulty in being consistent myself, then who am I, to harp about the inconsistency of others?

As regards lying, they say that there is “no such thing as an honest politician”. But that’s only because you can tell many stories about the same fact, emphasizing some things and de-emphasizing others, which are all valid or true; and a politician has to tell a story which is not only valid, but also responds to how people will interpret and act on that story. Which means that a politician can hardly “tell the whole truth with all the details” like a scholar, a lover or a parent might do.

To say that political utterances are political, means that they can affect interests, valuations and power relations among people, and thus that you cannot just spontaneously say anything you might like, because you have to be very aware of the effect of what you say. Mr Obama owed his success in good part simply to affirming the values which masses of people – people who often were disgusted with the Bush administration – actually have, and that is a very different thing from Marxists saying the working class is backward because “it” isn’t Marxist, and therefore, that they first have to go through the Marxist program so that they may be converted to revolutionism.

I wrote these comments not just for Todd, but for all those participating in this little discussion we were having. And if you, Todd, are still confused, then I think you ought to look first at your own confusion before implicitly blaming me for it.

Maybe Mr Obama cannot tell the whole truth, but I think nevertheless he can be credited with being a “principled” politician, somebody with integrity. Okay, I wouldn’t really agree with him about a bunch of things, but I would agree with him that a “politics of blame” is really a dead end, which gets in the way of doing anything constructive.

After all, if the problem is always somebody else’s fault, then the onus is on someone else to change, but that is precisely what renders people powerless, because not only is it very difficult to get somebody else to change, it also means that you yourself cannot do very much to make a difference, except keeping on “challenging other people to change”. Such a Leftist political style centered on blaming is just very weak, and has little result; the real challenge is what you can change yourself, even if only an idea, and how you can thereby influence others. You can blame the blacks, the immigrants, gays, the banks, the capitalists, popular delusions etc. with moral fervour and holy scorn, but by doing so you literally give away your own power and all this really achieves is, that you create more animosities and social envy. It does not tell people what they can do to make a positive difference or advance toward a goal. A “leader” is somebody who can show you the next step, because he knows how to do things, and get things done. You just don’t provide any real leadership, by wailing about how evil other people are.

“I do, however, think that Marx didn’t foresee just how powerful the modern state and corporation are. That is why it is so exasperating to see labor leaders refusing to try to build real working class power,”

The problem is most workers do not see themselves as a class anymore, all most people care about (at least among my generation) is money and toys, they could care less about marx, capitalism or other intellectually related stuff.

Most people are content not to think about things, the only way to change society is through actual real deprivation and crisis so that it spur’s people to join together.

Modern society in my opinion is even becoming more fragmented and factionated then ever before. Modern Japan women and men are loathe to have families, over 50% of both men and women are single. I think you really underestimate how wealth and the want of being rich and having an easy life corrupts people.

Vermillion, You may be right about wanting to get rich and how this corrupts people. And I agree that a lot of people don’t want to think too much. But on the other hand, lots of people do care and do think, so this gives me hope.

Have you ever considered adding more videos to your blog posts to keep the readers more entertained? I mean I just read through the entire article of yours and it was quite good but since Im more of a visual learner,I found that to be more helpful well let me know how it turns out! I love what you guys are always up too. Such clever work and reporting! Keep up the great works guys Ive added you guys to my blogroll. This is a great article thanks for sharing this informative information.. I will visit your blog regularly for some latest post.