III. Like everyone else, Clyde Yassem remembered what he had been doing on December 7, 1941. Sleeping. His parents and two of his younger brothers rushed in to awaken him and tell him the news. He didn’t think much of it at first, but as what happened became clear, he could see that it had electrified the town. People talked of little else, and within a few days, young men were driving, taking the train, or hitchhiking to the next town up the river to the military recruiting offices. A patriotic fever swept the nation, and everyone was now paying attention to events in Europe and Asia. There were no Japanese-Americans in Clyde’s town, but the many families of German ancestry found themselves suspect by their neighbors. Some teenagers had vandalized the German Beneficial Union club, after a report in the big city paper said that the GBU was a hotbed of homegrown Nazis.

III. Like everyone else, Clyde Yassem remembered what he had been doing on December 7, 1941. Sleeping. His parents and two of his younger brothers rushed in to awaken him and tell him the news. He didn’t think much of it at first, but as what happened became clear, he could see that it had electrified the town. People talked of little else, and within a few days, young men were driving, taking the train, or hitchhiking to the next town up the river to the military recruiting offices. A patriotic fever swept the nation, and everyone was now paying attention to events in Europe and Asia. There were no Japanese-Americans in Clyde’s town, but the many families of German ancestry found themselves suspect by their neighbors. Some teenagers had vandalized the German Beneficial Union club, after a report in the big city paper said that the GBU was a hotbed of homegrown Nazis.

So many young factory workers were enlisting that the management began to keep workers on the job for ten and sometimes twelve hours a day, something it hadn’t done since 1929. Thanks to the new federal law, hours over forty a week had to be paid at time and one-half the regular hourly wage rate, and this meant that the men, including Clyde, were bringing home record paychecks. But Clyde was as caught up in war fever as anyone else. He had a good number and might not have been called up in the draft the government had initiated. But he wanted to join up and fight the Japs. So, in May 1942 he visited the naval recruiting office. A friend had told him that you had a better chance to survive in the Navy than in the Army or Marines. He just made the weight minimum, and when the doctor asked him about the red marks on his knuckles, which were scars left from the tuberculosis which had attacked his bones as a child, he told the doctor that he had fallen. Remarkably, the physician didn’t probe further.

Before he left for basic training, Clyde Yassem married his girlfriend, much to the chagrin of his parents who were none too keen on Italian-Americans. This didn’t matter to him; he was in love and already planning to have a large family when he got back from the war. His wife would stay with her mother, and his parents would look after the cheap car he had bought a few months before.

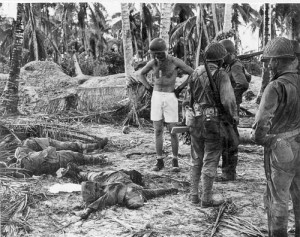

The war and his marriage seemed to change everything for Clyde. It sounds silly to say it but it was true—the war made him a man. It took him out of his small, provincial town, mixed him with guys from all over the country, put him in the best physical shape of his life (even if he did have to pushed off a rock to get him to swim), sent him far away to the South Pacific, showed him that he could face physical danger, made him a lifelong friend of the Samoan people, and taught him a skill. This last he had learned in temporary classrooms at the University of Chicago, where he was sent to radio school. Here he learned to take down and transmit code, to operate short wave radios, and to string wire in battle zones. Not many of his classmates made it through the school; for the first time in his life he stood out as someone who could do something not everyone else could do. It was stressful work, but he could do it calmly and without making mistakes. By the time he shipped out, he could light a cigarette while taking code and remember what had been transmitted while he was doing this.

Having a wife gave him a sense of security hard to put in words. It was evidence that he was a person someone else could love. He longed for the responsibility of a family, and from wherever he was, he cut pictures of children from magazines and sent them home. He also devised a way to trick the censors and tell his wife where he was when he got to the war zones. He told her that he would send a letter as soon as he could and that the second letter of the first word in every sentence would give her his location. She’d have to look in up on a good map. He was first stationed on the island of Funafuti in the Ellice Islands.

Clyde’s actual wartime service was relatively uneventful. He saw some awful things and a couple of close buddies were killed, but in the main, he did what he did and saw what he saw, and luckily, nothing bad happened to him and he didn’t come out of the war either physically or psychologically wrecked. One amazing thing happened one night while he was listening to Tokyo Rose. She sometimes “interviewed” prisoners of war, and on this night he heard the voice of a fellow from his hometown. His wife had sent him a clipping from the local paper reporting that this man was missing in action and presumed dead, a reasonable assumption since the Japanese didn’t take many prisoners and often killed the ones they did capture. After he heard his hometown boy, he wrote his wife, who when she finally go the letter, told the family. Their son was alive, and their lives were restored.

Like most of the soldiers in the South Pacific, Clyde came home a few months after the bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. First he was sent to East Texas where he was joined by his wife. She became pregnant not long after, but before their first child was born they were back in his hometown and he was again working in the factory. His hopes were high. A big strike was called not long after he started, and it was a great victory for the workers, who stood firm and solidly together, something many of them had learned to do in the war. You could count on your buddies and no on else, but if you did, you had a chance to get what you wanted, whether it was survival in the war or a fatter paycheck and benefits back in the civilian world. Clyde figured he would save some money and start a small business. He was envisioning a radio repair shop and had bought a used Hallicrafters short wave radio to practice on. He was also thinking about taking a correspondence course in drafting or something like that. Postwar America was an optimistic place, and Clyde had absorbed some of the good feelings all around him.

IV.

“Hey, Clyde, how’s it going.”

“Not too bad, Hap. My wife says I’m starting to look like a bum. I guess it’s time for a haircut.”

“Chair’s empty,” said Hap.

Hap Fidzik owned a combination barbershop and poolroom. He did alright raking his cut from the tables when the good players were hustling, but the real money came from selling numbers. He did a brisk business. Working men loved to gamble. Clyde did. He won a lot of money playing poker in the Navy. Men stuck on an island with time to kill were easy marks for a man who didn’t drink. He sometimes shot craps at lunchtime in the factory or caught a little action after work at a local club where there was always a game. When he had a dream about a number, he played it at Hap’s. Gambling got the adrenaline flowing, and he was a keen observer of the little ticks and gestures that played over guys’ faces when money was on the line. Win and even the cheapskates got generous. Lose and most lost their composure. Clyde liked it when other players said he was lucky. Maybe he was, but he played smart, watched his money, never lost the mortgage payment.

Hap Fidzik owned a combination barbershop and poolroom. He did alright raking his cut from the tables when the good players were hustling, but the real money came from selling numbers. He did a brisk business. Working men loved to gamble. Clyde did. He won a lot of money playing poker in the Navy. Men stuck on an island with time to kill were easy marks for a man who didn’t drink. He sometimes shot craps at lunchtime in the factory or caught a little action after work at a local club where there was always a game. When he had a dream about a number, he played it at Hap’s. Gambling got the adrenaline flowing, and he was a keen observer of the little ticks and gestures that played over guys’ faces when money was on the line. Win and even the cheapskates got generous. Lose and most lost their composure. Clyde liked it when other players said he was lucky. Maybe he was, but he played smart, watched his money, never lost the mortgage payment.

What Clyde enjoyed most were the horses. There were two racetracks an hour’s drive from town. One was for thoroughbreds, the other for pacers and trotters. He tried to get to a track once a week, usually on Saturdays, but with a family, he couldn’t always go. So he often booked bets at Hap’s. His approach was systematic. He kept a notebook with records from the newspapers of recent winners and near winners. He watched for hot jockeys and drivers. He noticed which horses were good in bad weather. Whenever he could, he got a copy of the Daily Racing Form in a nearby town and read and re-read every issue. His work was rewarded; he won consistently, not much since he didn’t have much to bet but enough to help pay the bills and allow for small luxuries like a take-out pizza or a trip to the drive-in hamburger stand.

For all but a few of us, optimism is hard to sustain without a surplus of money. Even union wages don’t allow for savings if a person wants to live a normal life. Clyde and his wife had a second child and then a third. To house their family, they decided to take on one of the new mortgages being guaranteed by the government and aimed at veterans like Clyde. They had a small house built on the hill overlooking the town. They couldn’t afford the plan with a fireplace, but still they got a nice house with a big yard, just right for raising kids. He planted a garden, and his wife canned beans, tomatoes, and peaches. Kids and a mortgage took up most of his paycheck, and it wasn’t long before Clyde tried to get as much overtime as he could. After ten years of factory work, he seldom thought of his old dreams of radio repair and drafting. He was a glassworker. There were worse things he could be doing. Like dreaming about things that weren’t going to happen.

“Clyde, you see these new football sheets?”

“What?”

“The football pool sheets. Every week, I get a bunch of them. College and pro games are listed with the point spreads. You can bet on one game, two games, or as many as you like. If you bet on more than one, all your teams have to “beat the spot” for you to win. The odds get higher the more teams you pick.”

“Sounds like a good deal for you,” Clyde said. The suckers will see the big payoff and not the sucker’s bets.”

“Yeah,” Hap said, “all you dreamers will make me rich.” Clyde could have been a wise guy and told Hap that he’d already contributed to more than one divorce, but he was thinking that here might be an opportunity to stretch his paycheck.

“Hey, Hap, I bet I could sell a lot of those sheets in the plant. I just bid on a job in the fire department. I passed all the tests and with my seniority, I’m a lock for the job. A fireman makes safety checks in plant every day, so I’ll be in every department in the factory. You get more time to do the safety inspections that it really takes, so I’ll have time to talk to the guys and sell them football sheets. Everybody’s an expert on football; they’ll eat these things up.”

“Clyde, I like that idea. Let me know when you get the job and I’ll set you up with the sheets.”

Within a month of starting his new job, Clyde was selling more than 100 pool sheets a week and earning at least an extra $50. Big money in those days. Even the foremen were buying them. Hap always paid the winners on Monday, and the site of happy men counting their money was the best advertising Clyde could get. By the end of the first season, Clyde was dreaming of a new car.

To be continued . . .