There is something astonishing about rock arches, and every time we see one, we marvel that nature could produce such works of art. How can there be such a thing as Landscape Arch, the longest in the world, an impossibly thin span of 290 feet, stretching like a rainbow between its sandstone moorings and made still narrower in 1991 when three large rock slabs fell from its thinnest part? When you see it, you almost expect it to collapse before your eyes.

Recently we hiked to view two amazing arches. The first one, which we have been to many times, is perhaps the most famous in the world—Delicate Arch in Arches National Park, near Moab Utah.  You may have seen its image on Utah license plates. It is the only free-standing arch we have ever seen; nothing surrounds it but the air. Here is how the great chronicler of the red rock country, Edward Abbey, described it:

You may have seen its image on Utah license plates. It is the only free-standing arch we have ever seen; nothing surrounds it but the air. Here is how the great chronicler of the red rock country, Edward Abbey, described it:

There are several ways of looking at Delicate Arch. Depending on your preconceptions you may see the eroded remnants of a sandstone fin, a giant engagement ring cemented in rock, a bow-legged pair of petrified cowboy chaps. If Delicate Arch has any significance it lies, I will venture, in the power of the odd and unexpected to startle the senses and surprise the mind out of their ruts of habit, to compel us into a reawakened awareness of the wonderful-that which is full of wonder.

The one and one-half mile hike to Delicate Arch isn’t difficult, although it is steep in parts. Much of it is on the smooth “slick rock,” which when the weather is dry isn’t slick at all. In fact, the soles of your shoes almost stick to it, so that you can walk down a fairly sharp incline almost as surely as a bighorn sheep. As you near the arch, you hike alongside a tall rock face that hides it from view. Then suddenly you come around a corner, and there it is. We always hold hands and keep our heads down until we know we are in sight of it. Then we look up and gasp. I imagine Adam and Eve awakening from their infinitely long slumber and finding themselves in the Garden of Eden. We find a spot on the rocks and contemplate the arch’s perfection. I scamper down the slick rock to stand under it. Karen takes some pictures. We strike up conversations with other visitors; somehow Delicate Arch makes people want to talk. We always hate to leave. If you are anywhere near Moab, don’t miss this hike. Seeing Delicate Arch is a transcendental experience.

The second arch we visited is Druid Arch, in the Needles district of Canyonlands National Park. This arch demands a much greater effort—an eleven-mile hike— than does Delicate Arch. The drive south from Moab (on US 191) to the trail head takes at least two hours. However, the landscape along the way is beautiful. Twenty-four miles into the trip you come upon massive Wilson Arch, which is right next to the highway. This was the first arch we ever saw, back in 1997. Forty miles south of Moab, we turned right (west) on Utah Highway 211. The park is thirty-five miles from here. The narrow two-lane highway traverses ranch lands lying in the shadows of rock cliffs and wondrous rock formations that look like castles and ancient fortresses outlined against the sky. Dirt roads lead into canyons, one aptly named the Beef Basin. This is open (unfenced) range, and we had to be careful not to hit any cows that had wandered onto the road. Springs and a creek provide some water in an otherwise arid place. Ranches cover extremely large land areas in the west because the parched earth offers scant food for stock; each animal needs many acres of scrub to survive. I read once that this region was part of a ranch occupying more than a million acres. Cowboys lived in the open, underneath rock overhangs, until the 1970s.

About eight miles along Highway 211 is Newspaper Rock State Historic Monument, a 200 square foot sandstone rock on which there are hundreds of petroglyphs, some 2,000 years old. We always stop to see the rock art; it has a magical quality and somehow makes us feel connected to the ancient ones who lived here hunting, gathering, and planting. Each of us is free to guess what the symbols mean. No one knows for sure.

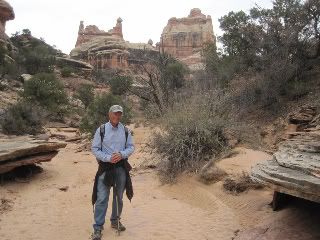

Once in the park, we followed the pavement to the Elephant Hill turnoff, a winding dirt road with several blind curves. It ends at the famous Elephant Hill jeep trail, a steep rock road that demands exceptional driving skills and a high-clearance, rugged, four-wheel drive vehicle. The trail that takes you to the arch begins to the left of the jeep road. We usually hike to Chesler Park, about three miles away. This time, however, we detoured and hiked to Druid Arch. Most of the walk is along the sand and rocks of a wash in Elephant Canyon (which has several branches), where rainwater and springs have created a lush and bizarre landscape of multicolored rocks, plants and wildflowers, and large juniper trees with twisting and turning roots.  At one point, the canyon is blocked by a large pool of water, necessitating a detour up and around the canyon floor. This part of the hike requires some care; there are narrow ledges and a steep dry waterfall to ascend. The trail rises into high cliffs, and we had to use a conveniently placed ladder and metal railing to help us over the hardest parts.

At one point, the canyon is blocked by a large pool of water, necessitating a detour up and around the canyon floor. This part of the hike requires some care; there are narrow ledges and a steep dry waterfall to ascend. The trail rises into high cliffs, and we had to use a conveniently placed ladder and metal railing to help us over the hardest parts.

As we approached what we knew had to be the end of the hike, we began to climb up. Where was that damn arch? In front of us was what looked like a tall, thin spire.  We worked our way up to the left of the spire, and then when we turned toward it, almost like a miracle, there was Druid Arch. What we had been seeing wasn’t a spire but the arch, seen “end on.” I can’t do the arch justice in words, so let me quote Abbey again. What he said about all of Canyonlands certainly applies to Druid Arch: “the most weird, wonderful, magical place on earth — there is nothing else like it anywhere.”

We worked our way up to the left of the spire, and then when we turned toward it, almost like a miracle, there was Druid Arch. What we had been seeing wasn’t a spire but the arch, seen “end on.” I can’t do the arch justice in words, so let me quote Abbey again. What he said about all of Canyonlands certainly applies to Druid Arch: “the most weird, wonderful, magical place on earth — there is nothing else like it anywhere.”  We sat and had lunch, almost startled by the beauty of the arch. The late autumn light would be gone soon, so we reluctantly returned to the trail. We were tired when we got back to our car, but we had been amply rewarded for our strenuous efforts. We had seen something remarkable. Like Delicate Arch, Druid Arch is not to be missed.

We sat and had lunch, almost startled by the beauty of the arch. The late autumn light would be gone soon, so we reluctantly returned to the trail. We were tired when we got back to our car, but we had been amply rewarded for our strenuous efforts. We had seen something remarkable. Like Delicate Arch, Druid Arch is not to be missed.

Our hikes to famous arches like Delicate and Druid have turned us into arch “hounds,” always on the lookout for new ones. We were hiking on the Moab Rim Trail, and Karen spotted an arch along a cliff. We walked over to get a better view. In case it didn’t have a name, we christened it Karen’s Arch.  In the distance were the rocky battlements created by the relentless knifing action of the Colorado River. From any vantage point, they look like eternal backdrops in a play that goes on forever.

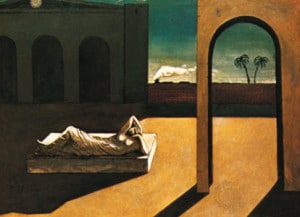

In the distance were the rocky battlements created by the relentless knifing action of the Colorado River. From any vantage point, they look like eternal backdrops in a play that goes on forever.  They reminded me of the “metaphysical” art of the Italian painter Georgio de Chirico. He painted urban landscapes that try to make us see the perfect Platonic forms that underlie what we think is reality.

They reminded me of the “metaphysical” art of the Italian painter Georgio de Chirico. He painted urban landscapes that try to make us see the perfect Platonic forms that underlie what we think is reality.  But de Chirico’s metaphysic is false. There are no true and eternal forms. There are only appearances, and these are always in flux. Some last a short time, like the artist’s paintings; others, like the rocks, last for millions of years. But all will turn to dust or sand someday. Only the universe itself might go on forever. Still, it gives me comfort to look at the arches, at the rocks around them, at the world we have but only partially created, and dream of those who came here before me and those who will come after.

But de Chirico’s metaphysic is false. There are no true and eternal forms. There are only appearances, and these are always in flux. Some last a short time, like the artist’s paintings; others, like the rocks, last for millions of years. But all will turn to dust or sand someday. Only the universe itself might go on forever. Still, it gives me comfort to look at the arches, at the rocks around them, at the world we have but only partially created, and dream of those who came here before me and those who will come after.

An inspiration, Mike. thank you!

A few years ago we hiked with our small children in the De-Na-Zin Wilderness (“Bisti Badlands”) near Farmington, making our way back out in a memorable snowstorm. Everything about your post here recalls our sense of humility, awe and also connectedness. You rock.

Andy, Thanks for the kind words. And thanks too for your story. One of the best things about hiking is the unexpected. But this can be scary too, especially something like a snowstorm. We didn’t know about the Bisti Badlands. Hopefully we’ll be able to get there sometime! Mike

Hi Mike,

I finally finished your book a few weeks back, definitely glad to have read it during our trip. This is a beautifully written entry and captures the awe I felt upon seeing the arches for the first time last month. The magnitude of the landscape and the petroglyphs certainly had me thinking of all who passed through there before me.

My husband, daughter and I made it to California and are headed down the coast. I know you and Karen have traveled throughout the Pacific Northwest, but have you hiked the Lost Coast? We camped way out in Mattole Beach in Petrolia (Counterpunch headquarters, but the town consisted of no more than a general store with attached post office) Beautiful coastline. I would also recommend another place we stayed, tiny Westport, CA in Mendocino County along Highway 1.

Happy Trails.

Rosa, Good to hear from you. Glad you like my post. Everytime we have wanted to get to the Lost Coast, something has come up and we couldn’t go there. Thanks for the tip about Westport. Have you ever heard the song “Talk to Me of Mendocino”? Check it out.