We’re driving in a dust storm somewhere in the Navajo Nation in Arizona. We’ve just passed “Church Rock,” and to the north in Utah is The Valley of the Gods. We can barely see the road, and the tumbleweeds are dancing on the highway, careening off the windshield and dashing madly across the desert. 660 AM is on the radio, the Voice of the Navajo Nation, broadcasting from Window Rock, Arizona. We listen to the Navajo language , not comprehending a word, waiting, and then the DJ says, “Skeeter Davis, The End of the World.” The interjection of English always startles us.

For ten years now, we have been driving the highways of the United States, sometimes stopping in a town for a year or so, sometimes just drifting from place to place. The last year-long stay was in Boulder, Colorado. We left there in February 2010, and we have been traveling ever since, living in cheap motels and still cooking our food on a hot plate. Like the song says, “I’ve been everywhere man.” If we meet you on a hiking trail, in a grocery store, or on the street, the chances are good that there is some place we both know about.

If you don’t know our story, here it is in brief. I quit teaching at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown in April, 2001. I taught there for thirty-two years, and, at fifty-five, the prospect of teaching uninterested kids for another ten years didn’t appeal to me. So, I gave my notice, called the pension administrators, and with Karen plotted out a new life. We gave almost everything we owned away. When our first plan—to move to New York City where I would work for Monthly Review magazine—fell through, we regrouped and got jobs at Yellowstone National Park. After that, we did move to Manhattan. From there, we lived in Portland, Oregon, Miami Beach, Estes Park, Colorado, Amherst, Tucson, and Boulder. When we left each of these towns, we took long road trips, with roughly planned itineraries, sometimes staying a couple of days in many locations and other times digging in for a week or a month in a place we really liked. We’ve been nearly a thousand days on the road like this.

What have we learned in a decade of travel, about ourselves and about our country? The short answer is “a lot.” The long answer follows.

We need adequate incomes to enjoy our lives, but just as important, these incomes need not and should not be so unevenly divided. In 2010, Karen and I had more than enough income on which to live. Neither rich nor poor, just about in the middle. This means both that roughly half of the population has less than us, and that everyone in the United States could have as much as we do. Everyone! While low incomes mean that too many people in too many places we have been suffer from an absolute lack of the food, clothing, and shelter we all need, the grotesque gap between rich and poor does more insidious damage. Those at the top gobble up all the resources: the houses, the land, public spaces they use their power to have privatized, the schools, the water, everything. They get the good stuff, and most of us get the leftovers. Just about everywhere, a small number of very rich individuals have driven the prices of land and housing into the stratosphere. They buy beautiful objects and travel to scenic places, while the lives of the majority get more pinched, isolated, and ordinary.

The great Lakota leader Crazy Horse said about the European settlers, “The love of possessions is a disease with them.” If he were alive now, he would be astonished at the needless consumption that more or less defines life in the United States. We are judged by what we own. When Karen worked in daycare in Pittsburgh in the 1990s, children as young as two would look inside each other’s shirt collars to see the designer label. They already recognized the letters GAP. Towns, housing and condominium developments, and hotels are typically advertised in terms of how many shops and restaurants are nearby. What are the streets of any city but monuments to shopping? There are at least two shopping channels on every cable television. We can’t get enough stuff. Watch HGTV (House and Garden Television), and you will discover that house buyers want large houses with several thousand square feet, enormous kitchens, and gargantuan walk-in closets. Three-car garages seem de rigeur. On shows that feature furnished homes and apartments, goods are everywhere: several televisions and computers, every manner of electronic devise, kitchen equipment galore—though so few families appear to do much cooking—scads of furniture, multiple bathrooms, jetted tubs, entertainment rooms with home theaters, man caves, hobby rooms, cars, trucks, boats, RVs, ATVs, mountain bikes, sports gear. And these are people who are not by U.S. standards wealthy. We met a man in his sixties in Gilbert, Arizona who loved and wanted to live in the beautiful Sabino Canyon area of Tucson. But he didn’t buy a home there because he said he got more square footage for his money in Gilbert.

We decided to keep our consumption to a minimum. After we gave our things away in Pittsburgh, we had to buy furnishings for apartments in Manhattan and Portland. When we left each of these cities, we gave away or sold cheaply most of what we had bought. So from then on, we rented furnished places. Today, except for some framed pictures, family memorabilia, and a few cherished objects that we have stored in the homes of relatives, everything we own fits in our minivan. Besides the car, we have laptop computers (for work, email, bill paying, banking, and news), kitchen gear, a radio, a space heater, a few reference books, CDs, and minimal clothing; we own no furniture, no stove, no refrigerator, no washer, no dryer, no bed. We have no home base.

Aside from replacing worn out clothing, shoes, and the like, the only shopping we do is for food. We rarely eat in restaurants. We keep a basic pantry in our car, and we shop for food nearly every day. Karen has an envelope full of coupons. We look for sales so we can stock up on items we use regularly. We have the “saver card” for most of the grocery store chains in the country. We utilize local farmers’ markets when we can. Using almost all organic products, we eat three meals a day. Our daily food budget rarely exceed twelve dollars.

We spend more time in grocery stores than most, but this has proven valuable; it is a good way to see interesting aspects of how our countrymen live. We talk to the clerks, the baggers, the stockers, the managers, and they tell us things about their town and their jobs. We watch how customers treat the workers. We observe when shoppers seem intent on finding the cheapest products and when they grab goods without looking at prices. We notice how many people don’t know how to use unit pricing, and how stores exploit this by making it appear that, for example, a twelve-pack of toilet paper is cheaper than a four-pack when it is not. And how package-size decreases—with the same price—are ubiquitous; a half gallon of ice cream is now almost always three-quarters of a half gallon. And most of all, how much of our food is junk, full of unhealthy ingredients, from trans fats to corn syrup to fillers of all kinds and disgusting ingredients like ammonia on meat. The sight of parents with young children filling their carts with prepared foods, cases of soda, and fat-filled snacks is too sad for words.

We have been amazed at how much time is available in a day when you don’t shop much or eat in restaurants. And when you’re not caught up in the relentless cycle of “getting and spending,”you don’t become anxious because you don’t have what your neighbor does. Instead of driving to malls or going from store to store on city streets, instead of buying things we don’t need, we enjoy getting our food every day, preparing simple meals, talking, learning about the places in which we find ourselves, hiking in beautiful mountains and canyons, on ocean cliffs and beaches, on the slick rock, seeing the sun rise and set, the stars in the Western sky, working and watching television late at night, just thinking (The Bureau of Labor Statistics “Time Use Studies” found that the average person in the United States spends a mere fifteen minutes a day “relaxing and thinking”). Everyone says life is hectic, too busy, too much to do. I wonder, though, if for most of us, there isn’t plenty of time; we just choose to waste so much of it consuming.

Living as we do has made us more adaptable, and better able to make good, quick decisions. On the road we have dealt with car breakdowns, accidents, automobile and health insurance claims, serious illnesses, surgery, injuries, credit card disputes, hassles with the IRS, a year-long effort to get the United States Postal Service to pay an insurance claim, difficult family problems, legal issues, apartment rentals. I have taught online college classes from motel rooms, and I travel to teach a class at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst every January no matter where we were living. Without an office or a desk, I have written several books, many articles and reviews, and blog entries. As a magazine editor and director of Monthly Review Press, I have edited articles and books and maintained correspondence with writers around the world. I usually work with a computer on my lap while lying in bed. On our hikes, we work through problems, make new plans, compose emails and phone calls in our heads. The chirping of birds and the wind giving voice to the leaves is far more conducive to clear thinking than a claustrophobic office and the misery of a long commute.

Modern life is one of growing entrapment. We are trapped by our jobs, by our inability to find jobs, by our low incomes, by our excessive consumption, by our homes, by our poor health, by our lack of health insurance. By the sheer boredom of daily life. We’ve broken free of some of these traps. We did this by refusing to keep working long hours in meaningless jobs when we didn’t have to, saving instead of spending, keeping on the move, eating less but healthier, and staying in good physical condition. So far, we have no regrets.

To be continued . . .

“We’ve broken free of some of these traps”

Certainly not the second-largest trap of them all: the filthy, toxic, expensive, polluting, murderous, dictatorship-funding automobile.

Nice article Mike. I think that you have beat the system in the past 10 years. Doing exactly what you want ot do. You are rright. Too many people are caught up the the consumer culture. Just about 10 minutes before reading this, I was talking with my 21 year son (Sam) about this very issue. I’m going to have him read this. I think you know how 21 year olds listen to their parents. Maybe he will pick up something here. Live modestly think and act big.

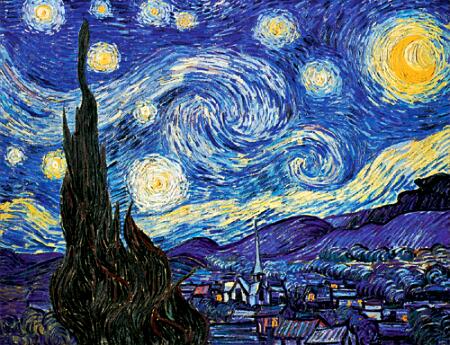

Where was the picture taken?

Well, Your Future, please let me know about the last ten years of your life, so we can compare notes. (to start, we both use computers–toxic, polluting, etc.).

Joe, Thanks for the note. I hope Sam enjoys the post! The photo is from Mt. Rainier in 2010, in July.

Mike, I’ve been living rather like you-both for about 17 years, but with the difference that I stay mostly in the one place. Gets rid of the need for much transportation.

I keep no car — which is another huge saving of money and angst. Instead I have bikes, a self-made, all-weather velomobile (not electrically assisted) and — because I’m old enough and live in outrageously-socialist Britain (joke!) — I have a free bus pass too. One of my bikes is a minute folder, and goes on buses as hand luggage.

Potent — and very inexpensive — transport combination.

Also, as well as a single electrical hotplate, I have a (self-made) rocket stove; amazingly-economical cooking device, using odds and ends of small stuff for fuel, harvested quickly and easily just for the cost of a leisurely dog-walk with rucksack, just as Larry Winiarski and his development team intended.

Like you, I can recommend highly the liberation, serenity and extraordinary viability of the non-consumerist lifestyle, even with a very small income. In Britain, I’m deemed by official statistics to live below the poverty line. In fact I live very comfortably, lacking no essentials at all, and — I think — enjoying life much better than people around me who have much greater money-flows passing through their hands, but who also have no peace nor any real, intense satisfaction in life, because they have the consumerist hook lodged firmly in their throats, poor bastards!

And what are they all going to do, how will they cope with the big psychic shock, when the consumerist lifestyle, and the bloated incomes that it demands, both go down the tubes together, now that the era of growthforever has just died in the first decade of this century, superseded now by the opening of the new era of shrinkage and shortages?

As Dmitry Orlov pointed out just recently, those people who hallucinate the idea that they’re wealthy, because of all the bits of hyper-transient paper and pixels which they hold (for the moment), are heading for very big, deep shocks when their ‘wealth’ has mostly evaporated like the morning dew under the remorseless cumulative impacts of the new era, and they have to cope with their own cold-turkey transitions to the style of life to which we have acclimatised, and actually enjoy.

I have absolutely no desire to change places with those unfortunates. Rather, I encourage anyone who’ll listen to join us, voluntarily, in good time, in the serene frugal lifestyle. Much better!

However, there is one other aspect of this matter which needs a bit of thinking about. Because I live in the one place, it’s possible for me to be a member of a Community Supported Agriculture scheme: weekly supplies of cheap, organically-grown vegetables at keen prices, direct from the farm. But the young farmers who run this scheme also include work-mornings several days a week, to which all members of the scheme contribute labour; and they run a programme of regular social events on the farm too, with bring-and-share food, and many entertainments, so that a strong community of people has already formed around this CSA.

As the new era enforces a whole lot of upheavals and dislocations on the consumerist way of life that the Pampered Twenty Percent of the world’s human population have suffered in recent decades, that mutually-supportive community of cooperating friends and neighbours — already in place and maturing nicely — is going to be an absolute must-have, I think. Another benefit of settling in the one place?

I bailed out of wage-slavery at a university library when I was 55. I was more than a little nervous about whether I could actually live on the little I had in my meagre pension. My taxable income puts me in the 15% bracket to this day. Now, I’m 66 and glad I made the great escape. I’ve written a novel, some short stories, poems, book and movie reviews. I also managed to get a brown belt in free-style martial arts and still spar at my dojo. As Marx said, disposable time is really where wealth is at for the individual. I’m so glad I didn’t stick around wasting my time wage-slaving for the bosses.

Good day folks. There is an aspect of your lifestyle that intrigues me and yet goes unaddressed in your article: how transience relates to (your) communal lives.

I appreciate the appurtenances of the info-age have somewhat attenuated the definition of community but, to my mind, the real psychological need for a sense of belonging can often only be satisfied by a stationary, stable existence fed by enriching networks of economic and social interdependencies. Of course, individual disposition bears on one’s inclinations here and you may indeed be among the exceptions that prove the rule.

Still, a more constant life, rooted in its history and engaged in its community, better fosters the relationships required for generating real wealth and fulfillment, to wit, a culture of shared experience, purpose and achievement. I wonder to what degree a lifestyle of perpetual motion, such as yours, limits these prospects.

I find this all very interesting. In my household, we’re still living somewhere in between the typical American consumerist lifestyle and the all out frugal lifestyle I see Mike and others discussing here. We have no debt, no cable/satellite TV (although we watch DVD’s from the library), no electronic gadgetry other than cell phones that are several years old and a desktop computer that’s on it’s last legs. We’ve never been recreational shoppers. We garden and do some food preservation, but not nearly enough to subsist on entirely. I’m fortunate to have a job that has decent vacation/leave and health benefits. For the most part, it gives me time to have a life outside of working and commuting like few other jobs would. I hate my commute, but the choice we had was live in a walkable, bike-able community that allows us to leave the car in the garage for many errands (or just going downtown on a nice evening) but a long commute for me, or we live in an automobile-centric exurb where my job is and have a short commute but be forced to drive for absolutely everything else.

Long story short, we try to live below our means as best as we can. We’re not perfect, but we are ahead of most.

Although we live a healthy lifestyle, with the state of healthcare in the US being linked to full time employment, it makes it difficult for those of us who are not pensioners to break as freely from the system. This year, I had a complication from what was supposed to be a routine outpatient surgery that, without health insurance, would have turned a $1500 bill into nearly $40,000 (a big nip at our savings) and several weeks off work (thankfully my employer has a disability benefit). It’s easy not to consume. Unexpected medical bills, even if you are healthy, is another matter entirely.

One question for Mike–and this merely a curiosity, nothing more–what are your plans when the peak oil noose begins to tighten in a few years (after 2014, according to the Pentagon)? I’m still working on that one for me… not much time is there?

Also, I agree… the US has a severe lack of community, and to our detriment.

Rhisiart, Thanks for your interesting note. We love to learn of people who have made themselves so much more self sufficient than we are. Yew, we wonder what people are going to do when life as they know it becomes more and more unsustainable. And at the same time, so many in the world who have to raise their consumption just to survive.

Luke, Your comments connect to what Rhisiart says. We haven’t found much in the way of community in the United States, at least where we lived before we took to the road. We hope to find some somewhere, sometime. It will be necessary to find some community if humanity is to survive at all I think. For us, for now though, we’re probably still making up for lost time, wanting to see as much as we can. We miss friendships sometime, however. But this system seems to fracture them beyond repair all too often.

Ed, Thank you for your note. We enjoy hearing about other people’s efforts to cope with what really is a deranged system. Your story about medical care is on the mark. Maybe one reason we don’t have the national health care we should all have is that this keeps our noses to the grindstone. We have a choice–stay on the job or fend for youreself if you get ill On oil, well that is a great question. Collective struggle will have to be one thing we engage in, to fight for community, public transport, renewable energy, and everything else we should have a right to.

Great essay, really amazing choice of living.

Two questions, prompted by curiosity:

1) Without getting too personal, since we all need our privacy, especially in a partnership: most “dropping out” is done by one person – is it harder for two to agree on that radical step? How many marriages could sustain both of your commitments to such a life of moving around together?

2) Can Monthly Review ever get more writing such as yours in this blog that is down to earth? I am having trouble each month connecting with the insider theoreticism – that may be my own rejectionism working.

Martin, I am sorry to take so long to reply. This is a good question. Probably not many couples would do what we have done. We have been of like mind about most things, and we both wanted a radical change in our lives. Lving at Yellowstone was a big breakthrough in terms of how we thought about life, and the rest flowed from this. However, it isn’t always easy to live like this, and we have arguments like any couple. If one of us wants a different life but not the other, then we’ll see how we handle that!