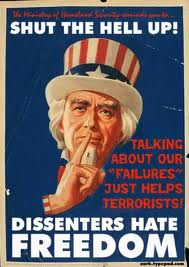

Workers in a hospital are sick of management violating their collective bargaining agreement. Their work is ever more stressful: hours keep getting longer; patient loads rise; safety rules are ignored. They tell their union steward that it is time to bombard the bosses with grievances before they explode in rage. He tells them, “You better not do that. You’re lucky to have a job.”

Workers in a hospital are sick of management violating their collective bargaining agreement. Their work is ever more stressful: hours keep getting longer; patient loads rise; safety rules are ignored. They tell their union steward that it is time to bombard the bosses with grievances before they explode in rage. He tells them, “You better not do that. You’re lucky to have a job.”

In every industry in the United States, there are more people seeking employment than jobs available. Conservatives and liberals alike say we have to put men and women to work. They differ in how they would achieve this, but both shout out the mantra, “jobs, jobs, jobs.” Little is ever said about the kinds of jobs that need to be created. What will they pay? Will they provide benefits? Will they be interesting, safe, fulfilling, socially useful?

Perhaps the reason we don’t ask such questions is that we take our work for granted, beyond our control and as inevitable as the rising sun. But looked at in the long sweep of human existence, the jobs we do and the way we do them are unlike anything we did before the rise of capitalism.

For most of our time on earth, we both conceptualized our labors and performed them. There was no separate group that figured out what we should do and then ordered us to do it. All work was skilled, and the pace and location of it were determined by us. No sharp distinctions were made between work and other social activities. It is true that with class societies such as slavery and feudalism, we were severely exploited, but even in them the unity of conception and execution remained mainly intact. To the extent that wages were paid, they were set by custom and tradition and not by an impersonal market. Unemployment was unknown because we were tied directly to the land and tools that, with our labors, gave us sustenance.

Once capitalism entered the world stage, the jobs we performed and the work we did underwent profound changes. The connections we had to the land were torn asunder, and we became radically “free,” free of what allowed us to live. To survive, we were forced to become wage laborers. In capitalism our capacity to work thus became a commodity, something bought and sold. The buyers, our employers, owned this capacity just as they owned the buildings, and like any privately owned property, the owners were legally free to use our labor power as they saw fit.

Our bosses, themselves hired managers, had one goal—to see to it that their companies made as much money as possible. Then the capitalists took the profits and expanded their businesses. To make these things happen, they did whatever they could to convert as much of our labor power as possible into actual work effort. This, in turn, dictated that our employers control the way we did our jobs as tightly as possible. No matter what goods and services we produced, we could not be allowed to interfere with the smooth flow of labor, tools, land, and materials into saleable commodities.

Capitalists have employed a variety of “control mechanisms” to accomplish their goals. They herded us into factories, so that they could watch us and make sure we worked with due diligence for as long as possible each day. Factory whistles told us when to begin and when to end our daily labors; failure to obey their commanding sounds resulted in us being disciplined or fired. The managers who observed us discovered that we divided our tasks into simpler details, to make our efforts more efficient. Why not, they reasoned, assign different workers to each detail, and in this way economize on skilled labor and lower the overall cost of producing a pair of shoes, a straight pin, or a piece of meat. When they had to, they hired women and children to do the least skilled jobs; they got the kids from orphanages when we wouldn’t send our children into the dark, satanic mills.

Repetitive detail work lent itself to the introduction of machinery. Soon series of mechanically connected machines were configured into assembly lines. These controlled more completely the pace and intensity of our work. In Karl Marx’s famous words, we became “appendages to the machines.”

Once these basic mechanisms were employed, industrial engineers and scientists systematized everything, and control became ever more refined and insidious. The process was complicated, but the thrust of it was simple. The engineers studied our motions and how long it took us to make each one. They then reorganized these to minimize both, demanding that we carry out each job’s motions and times according to their specifications. Or else. They began to recruit us systematically, with batteries of tests and interviews, so that those of us hired were best suited to take orders and labor as we were told. The bosses instituted “team production,” so that, in military fashion, we were inculcated with a sense of duty to our team members and not to the working class. Our jobs were continuously stressed—by speeding up the assembly line, reducing the number of members in our teams, denying us materials. Then they pressured us to figure out how to get production back up to standard. We soon learned that there would never be relief from the stress.

The great capitalists organized the markets in which we toiled so that core firms—automobile manufacturing plants, for example—were surrounded by parts supplier plants—such as those producing automobile steering assemblies. The supplier companies delivered the parts “just-in-time,” that is, only when needed by the core companies, thus saving money on inventories, storage space, and, most importantly, our labor. Employers also used modern electronic technology and the enormous pool of underutilized labor worldwide to offshore and outsource as much production as possible to places with lower wages. They used their tremendous political power to get governments to do their bidding: through laws, subsidies, tax breaks, and austerity measures that raised our economic insecurity.

It might be argued that tight managerial control was the price we had to pay for decent wages, benefits, and a modicum of security. Unfortunately, the bargain was a false one. In this richest of countries, nearly 28 percent of all jobs pay a wage that, with full-time, year-round work, would not support a family of four at the meager official poverty level of income ($23,021 in 2011). Wages have stagnated in terms of purchasing power for the past forty years; for production and nonsupervisory private sector workers they are barely higher today than in 1973. Fewer and fewer of us have pensions other than social security, which itself has become less generous. The same can be said for health care, paid vacations and holidays, and paid leaves, none of which are legally mandated. Unemployment and part-time work threaten all of us, and insufficient employment is made more likely both by the control mechanisms described above (for example, the job displacement effects of mechanization and outsourcing) and the greater likelihood of financial meltdowns in the global economy. Except when the federal government extends the coverage of the unemployment insurance system, fewer than half of us even qualify for benefits.

We have resisted control when we could. But whether we did or not, our work became ever more controlled and stressful. On the automobile assembly line, workers labor fifty-seven seconds out of every minute. At a Nabisco plant in California, employees had to wear Depends diapers because there were no mandatory breaks. Hotel room attendants have to clean more than twenty-five rooms a day. At a Walmart in Alabama, a supervisor punished some infractions by his team by making them have a thirty-minute meeting in the freezer. In the booming North Dakota oil and gas fields, workers suffer “burns from hot water,” “hands and fingers crushed by steel tongs,” and “injuries from chains that have whipsawed them off their feet.” Pick a workplace, any workplace: call centers, chicken processing plants, grocery stores, hospitals, colleges. A litany of horrors awaits us there. Our bodies and minds are ever more the worse for wear because we work. We are all, like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, caught in the tentacles of mechanisms beyond our control.

A recent Facebook post gives us a remarkable insight into work life today. When the phrase “work makes me . . .” was made the subject of a Google search, here are some of the words Google put forward as the most common endings to this phrase:

depressed

suicidal

nervous

feel sick

ill

anxious

tired

unhappy

sick

cry

Where is “joyous,” “happy,” “feel socially useful,” “human,” “more physically and mentally developed.” We can’t imagine such endings. What an indictment of that which should be an integral part of our lives, something that gives us worth and shines a light most brightly on the essence of our humanity.

* This essay was first published in counterpunch: http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/02/01/the-perils-of-work/

All this parallels my working life, spent in a locomotive, barreling to who knows where, on call 24/7. It was relentless by design it seems. The union, of which I was a local officer, was somewhat complicit in this, continually negotiating the right to work more in contracts (all negotiated at the national level) and selling it to the membership as a raise in pay. This right to work more soon became a duty to work more with most attempts to take a weekend off regarded as a “failure to protect your assignment”, although your “assignment” was to be ready to go whenever the next train shows up, whenever that may be.

I can’t begin to explain the cumulative effect of continual sleep deprivation, non-existent schedules and the like have on your health and quality of time away from the job, what precious little there was of that.

I gave up. They beat me. I’ve never felt better.

brunssd, Thanks for these comments. You were really a “just-in-time” worker, expected to be ready every minute of every day. I read that fast food places now demand that their employees be ready to work small fragments of what used to be a regular shift. They are expected to show up for work on a moment’s notice, just-in-time, to work maybe an hour, or even less. Glad you got out of the rat race. Take care and enjoy life!

I guess if we planned our work for ourselves, it would become more meaningful. Maybe some scientists and doctors are able to plan their work and for some artists, work may remain meaningful. But for most of us, work is only meaningful in the sense that we mean to pay the mortgage or rent, put food on the table and help feed our loved ones. We work to live. We sell our labour power for a wage because we are obliged to. We are wage-slaves. We are lucky to be employed as cogs in the wealth producing machine. The fear of being without a wage, of being unemployed drives us and fear eats our hearts.

Back in 1881, Engels wrote, “In a previous article we examined the time-honoured motto, “A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work”, and came to the conclusion that the fairest day’s wages under present social conditions is necessarily tantamount to the very unfairest division of the workman’s produce, the greater portion of that produce going into the capitalist’s pocket, and the workman having to put up with just as much as will enable him to keep himself in working order and to propagate his race.” http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/05/21.htm

What was true yesterday is still true today mostly because we’ve been sold on the idea that in this best of all possible worlds there is no alternative to striving for, ‘fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work’. We’ve been sold down the river by those who have been ‘boring from within’ only to be assimilated by the Borg (aka Capital), as the boring ones have attained cushy jobs in the political State or elsewhere in upper levels the bureaucratised capitalist hire-archy. And nowadays our class consciousness is at such a low level that we buy into all sorts of obfuscating notions about who we are and what part we play in the production of all wealth not already found in natural resources. We are so atomised as individuals, so alienated from political power that we end up embracing identities which do not threaten the dominant paradigm of our masters, the social relation of Capital. We are not working class producers; we are human resources. We are not working class; we are middle class. We are not working class; we are Jewish, African American, women, Palestinian and so on…. We are consumers; the producers are brand names belonging to our corporate employers. The resistance of the left, which mostly boils down to, ‘fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work’ radical liberalism, has been futile.

And our masters in the capitalist class, how are they? Wealthier and more politically powerful for sure. But they are also caught in the inertia of Capital’s systemic drive for growth, chugging the human race along like lemmings off the cliffs of climate change.

Mike B., This is well put. The capitalist system is an all-encompassing one that puts enormous pressures on us to act in ways that perpetuate the very system that makes us act in such ways in the first place. It seems clear that we must struggle to abolish it root and branch. Some say that we shouldn’t talk about catastrophe, that this is disempowering somehow. But what is daily life but a daily exercise in coping with catastrophes. We are indeed right now in the midst of devastating climate changes. If this isn’t a catastrophe, what is?

To add to this, part time inside workers face this kind of problem at UPS except the issue is the hours keep getting shorter even when we have large volumes to work with. The company picks the length of the working day one day ahead of time and typically picks the lowest amount of hours they can give us based on our contract: 3 1/2 hours. They then try to get all the work done in about 3 hours and get us out of the building. Recently they have been threatening to cancel entire shifts due to people saying they want to work their 3 1/2 when the day ends early.

Each year the company makes a decision on the amount of work per hour that workers should be doing, not because they gave us better equipment or fixed what we already have, just because they want to push more out. Due to the fact that they’ve decided we should be more productive they determine that we are “light” on work so they try to send people home or tell them not to come in(even though they have a right to work). This leads to situations where a loader will have to load 3-4 trucks at the same time because there simply aren’t enough people working. It also means that the supervisors end up loading and unloading trucks along with their workers, which is a big a contract violation but most people are too scared to grieve about it. When you are light on staff, heavy on volume, you have to cut corners to get your job done and thus you are always guilty of some kind of safety or quality violation. The supervisors ignore these violations when it adds to their productivity, they take note when you bring up the contractual issues.

They have been more and more egregious lately and it frightens me because we are renegotiating our contract. What scares me even more is that from what I have heard the Teamsters want an early settlement.

Most workers I work with do not think the union looks out for them at all. I once asked our shop steward about getting breaks during the winter when the part time workers work for 8+ hours in a single shift. I was told to hide in the bathroom.

I don’t know what the solution is because the IBT isn’t looking but I am happy to see writing that acknowledges the problem. I really enjoyed the article.

Mike, thanks for this detailed comment. It seems that the stress of work really does know no bounds, and things keep getting worse. Hide in the bathroom. What a thing for a union steward to say! No effort made at all to fight back against this, either by the steward or by the national union. This is a disgrace. Check out some of the things written about Jerry Tucke in Labor Notes for how workers can resist and win in these situations.

I’m increasingly convinced that there are two quite different ‘DNA’ strains in humans.

I just can’t wrap my mind around a mentality which appears to take such energy and glee in mercilessly grinding other humans into the ground, while largely feeding off of their labors and needs.

I’ll lay odds that 99.999% of “Work” now, is utterly antagonistic to an actually benign life sustenance.

Diane,

Probably because the capitalist system has a logic that requires employers to do this. Your last sentence is no doubt true.

Thanks for the comments.

Michael

You’re welcome for the ideas. Nice of you to eventually wake up, despite your own comfy professional progressive lifestyle of privileged Econ-Bro hipsterdom.

Why’d you always argue it was just about “jobs” over at SimBeeva?

Paul,

I don’t know what you are talking about. I have been writing about work for a long time, always with the same message. Plus no need to be a smart aleck.

You don’t know anything about me. I don’t know what your last three words mean. Perhaps you can explain.

Michael

Comedy of a very low calibre, intellect of a non-starter type, pretense of the most magnificent stratum. Someone should stop you before you vote (metaphorically speaking) for Marx again.

Oh, by the way — playing dumb only works when you’re actually smart.

You’re not playing.

Your comments about work/jobs at Simulated Beaverland are very interesting, as is this comical blog that has some huge blind spots.

Marx forever! More jobs! People need to buy, they need to consume! We’ll put professional Marxologists in all the key Cabinet spots when the Leftist Revolution arrives, and that will fix everything! Everyone will have a bland job working for one of the state’s bloated organs, but at least they’ll be able to buy a Prius and an iPhone!

Brother Bearer, you really area a dumb shit.

Thanks, Mike, for a short and sweet summary of the wage slave’s dilemma. Your article reminded me of two old Bolsheviks I knew, Joe Norrick and Vito DeLisi. I knew both of them in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s when I worked as a municipal sanitationman, (aka: “maggoteer”)and I went ahead and organized a union. Norrick — an early CPer from the UMWA — then the ill-fated NMU coalfields strike — told me the story of how he once watched a strike at a Gary, Indiana, plant where the workers poured out yelling that they were on strike because the place was run “like Modern Times.” And while telling the story he did the Chaplin wrench turning motions that he related was being done en masse by a couple hundred strikers who were enjoying the first minutes of their strike. Vito DeLisi was a staunch “SLP man” from the Michigan auto plants and a MESA leader in his day. He saw that my organizing was weighing on me, and I was stressed since at that point in my 18 years it was the best job I had ever had. I was living on my own, and so, “What if I get fired?” DeLisi told me that I had it all wrong; the whole concept of being “fired” or being “unemployed” was a stigma created by the bosses so that workers would beg for crappy jobs at miserable wages. So what if I got fired he says, I would pound the pavement and get by, probably find a better job. He gave me an old worn-out copy of “The Right to be Lazy” by Paul Lafargue. I still have it. He also gave me DeLeon’s “Ten Canons of the Proletarian Revolution” where DeLeon declares that Marxists must be “irreverant” and be able to debunk the bosses claims to reverance, as if the wages system was part of the natural order that could not be questioned. Norrick and DeLisi each in their own way were good radicals; they knew well that this system is rotten, it exists by sucking the life out of workers, and it torments to the breaking point hundreds of millions. Thanks again.

Chris, Thanks for this. The system does such the life out of workers. But how can the labor movement address the issue of the wage system? This is where we need a larger movement.

Well for starters, the unions can make an effort to teach the membership the facts of wage slave life. We do it in UE to some extent, but could do better. Your works and efforts have aided that necessary undertaking for many years now, and for that you should be thanked. And keep it up!

The worst offense for the unions to commit is to peddle the backward notion that all we want is “A fair days pay for a fair days work.” or some equivalent nonsense. Include in that all the beggings by so much of the labor leadership to “please help the middle class”, etc. And we sure do a larger movement, labor and left both.

Good luck out there wherever you are this time of year. Enjoy your freeedom!

After 45 years in the workforce, I realize that I’ve spent most of my life in fear, fear of being written up, suspended, fired. It finally happened, two years short of early Social Security retirement, the only retirement plan I had left after the housing crash of 2008. Realistically, no one is much interested in hiring a 60 year old Certified Respiratory Therapist. But there is an up side to it all. Once there’s nothing left to fear, who knows what I might accomplish for myself and my class? What are they gonna do, kill me?

Paul, thanks for this. Fear traps most of us. I hope your accomplishments are just beginning. Take care.