Clarity of thought is rare in the United States. This is not surprising given the constant barrage of propaganda to which we are subjected during every waking hour. Nowhere are systematic falsehoods presented as truth more than with respect to the nature of our economic system. I have discussed this before, but here I want to focus attention on working people’s understanding of our political economy..

The edifice that is capitalism is built upon a foundation of exploitation. Profits derive from the ability of employers to compel workers to labor longer than necessary to meet their basic needs. Employers are able to do this because they monopolize the access to the jobs workers need to survive. Without exploitation, neither profits nor the growth they make possible could exist; indeed capitalism itself could not exist.

In modern capitalism, there is precious little that any worker can do to guarantee his or her employment. It would be a contradiction in terms for everyone to be an entrepreneur. Furthermore, there is not much individual workers can do to make their pay and benefits higher once on the job. Overwhelmingly, we are replaceable cogs in some production machine, and our employers will make us aware of that should we become too demanding. We can do nothing to stand out in a way that would make the boss pay us more money. And if we are young enough to make pre-labor market choices, we will soon enough discover that what determines whether or not we “succeed” is circumstance and not our own qualities. The wealth, education, and social connections of our parents, the state of the economy when we begin seeking employment, any number of public policies, and just plain luck—these are what matter most. There is no such thing as the “self made” man or woman.

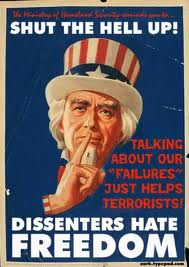

Yet though this is all true, the web of propaganda that envelops us would have us believe (and succeeds all too often to make us believe) that the opposite is true. There is no exploitation. We are free to choose our employment and indeed the life we want to live. Profits are the just rewards for the skills of the owners of our enterprises. Wages are the rewards for our labors. Whether they are high or low depends on what we do. Bill Gates and Warren Buffett are geniuses because they are so rich; they made the correct choices. The workers who deliver groceries on bicycles in New York City are ignoramuses because they are so poor; they made the wrong choices. The unemployment are beyond the pale because they have no money; they made very poor choices indeed. We cannot be exploited because, in the words of Milton Friedman, we are “free to choose.” If we are abused by our employers, that is “on us,” as they say. If we apply ourselves, work hard, persevere, be enthusiastic, seize opportunities when they present themselves, we can be anything we want to be.

Today in the United States, all too may working people believe the propaganda and do not believe the truth. I think that the main reason for this is that there are not nearly enough working class organizations, such as labor unions and worker-centered political and social organizations to show workers otherwise. The daily experience of work provides plenty of evidence that we are exploited and that individual effort and all of the virtues that Oprah Winfrey and her ilk advocate every day don’t count for much. However, this experience will only mean something if it can somehow be contextualized, that is, fitted into a coherent world view, or what amounts to the same thing, an ideology. For this to happen, workers have to engage in collective efforts to challenge their exploitation, and this presupposes that there are already in existence ways of thinking that are the result of intellectuals(who might also be workers) thinking through the meaning of such collective actions. For example, the work experiences and social interactions of skilled craft workers taught some of them that they could get better pay if they stuck together and refused to work for any employer that would not meet their demands. Over time, this developed into a powerful principle. Other actions, in workplaces and in the political arena, gave rise to new principles and a deeper understanding of how the capitalist system worked, for example, “An injury to one is an injury to all.” Then an intellectual like Karl Marx took everything that had gone before in terms of struggle and understanding and built a thorough and scientific model of the entire economic system, from the perspective of the working class. He got right to the heart of the matter and exposed the truth of the edifice and the foundation of capitalism. From this came the greatest of all worker-centered principles: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.” After Marx, it became the duty of every critical thinker and every working class organization to make this principle the basis of their work. A union must educate its members about this principle. Teachers must educate their students. Nothing is more important.

The fact that most workers in the United States today are not so educated results in what we might call “disconnects.” These are divergences between the thoughts and actions of workers and their true interests. We can be sure that those with power (the powerful more or less coincide with those who control the “commanding heights” of the economy—not just the owners of large businesses but also the attorneys, lobbyists, politicians, top military officers, and the like who serve their interests) will do whatever they can to ensure that workers believe the propaganda and not the truth about the system. If they are not challenged by the workers’ unions, political and social organizations, and intellectual supporters, then workers will not have an alternative way to look at the world. They will therefore either embrace the views of their class enemies or be prime targets for all manner of crackpots and charlatans, from religious cranks and idealists to nativists and conspiracists.

Here are some examples of “disconnects”:

* The public school teachers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania built a powerful union and broke once and for all the arbitrary power of the school board to determine how the teachers worked and pay they received. To win their union they struck, defying court injunctions even after their union offices were padlocked and their treasury impounded. Yet not one of these militant unionists stood up for my sons’ refusal to say the Pledge of Allegiance. In fact, the teachers treated my sons as if they had committed a crime.

* There is no question that the government responded to the rise of a militant and working class black movement in the 1960s and 1970s by the mass imprisonment of black men and women. This was compounded by the decline of U.S. manufacturing, which disproportionately harmed black workers, and because of the resulting unemployment and its effects, led to further black imprisonment. Those imprisoned are overwhelmingly workers. Yet white workers and unions have given this little thought and, if anything, have accepted the mainstream analysis that there is something wrong with the character of black persons and with the family structure of the black community. The U.S. labor movement has never, to my knowledge, publically and forcefully condemned the racist and anti-working class nature of the prison system.

* Today, wars are almost always connected to U.S. imperial interests. Yet, working people continue to send their children off to war and seldom make this connection.

* Workers are too often prone to blame unions for whatever ails the economy. How can this be?

* Unions themselves too often mimic in their internal structure that of their presumed class enemy and, in the process, alienate their own members.

I could go on, but you get the point. These disconnects and many more like them are the result of the failure of a mass working class movement to take hold in the United States and the failure of whatever working class organizations do exist to develop a worker-centered way of looking at the world and educating workers about it. Of course, none of us is completely consistent in our words and deeds. However, until we do something to connect the minds of workers to the reality that generates the conditions that allow them to be exploited, we will not be able even to begin the long struggle for human liberation.

Thanks Mike for an excellent essay.

It is spot on that working people do not have intellectual or theoretical resources to understand the nature of this rotten capitalist system. Yet on the other hand they have to deal with the empirical reality of it.

We seemed to be overwhelmed and crushed by the weight the ruling classes’ propaganda.

I was listening to Doug Henwood’s recent interview with you the other day. And I was thinking what if this type of discussion would reach the listenership numbers that the likes of Limbaugh, Beck and O’Reilly have? I would think that things would start clicking in peoples’ heads that a better alternative to capitalism would be possible.

Good that you brought up Milton Friedman, since not only have ideas influenced economic policy for the past thirty years or so, but they have also been key to the popoganda campaigns on behalf of neo-liberal economics.

Milton Friedman in his 1962 book, *Capitalism and Freedom*, famously argued that a free market capitalist economy was a necessary requirement if political freedom and democracy were to flourish. He admitted that not all capitalist societies were democratic and that not all them safeguarded political freedom but he argued that as an empirical matter, there were no “free” societies around that not also capitalist. He also made the argument that a free market economy was necessary to provide checks against the ambitions of the state, and so in that way acted as a necessary basis for the preservation of political freedom and democracy. That’s also how, years later, he could justify his giving economic advice to the Pinochet government, which clearly was hostile to both democracy and political freedom, since while Pinochet himself might have been a fascist thug, his economic policies, so Friedman argued, were conducive to the eventual expansion of liberty and democracy.

There are, however, several problems with Friedman’s arguments. First of all the claimed correlation between economic freedom and political freedom is not as simple as Friedman made out. Friedman claimed that “democratic socialism” was an oxymoron. A “democratic socialist” society, in his view, would either in time become undemocratic or it would revert back to capitalism. However, his argument does not take into account that though most of the West, the expansion of political freedom coincided with the spread of social democracy. The Scandinavian countries, for instance, back in the 1960s and 1970s managed to develop quite extensive welfare states at the very same time that these societies were also exapnding the range of personal and political freedoms that they were willing to protect,

Back in 1968 the Canadian political philosopher C.B. Macpherson wrote, what I believe to be one of the most effective demolition of Friedman’s arguments in his essay, “Elegant Tombstones: A Note on Friedman’s Freedom,” which first appeared in the journal, Canadian Journal of Political Science in March of that year. The following paragraphs should give the reader some of the flavor of Machpherson’s critique of Friedman.

Here, Macpherson takes on Friedman’s contention that free market capitalism is noncoercive in nature. That contention is one of the basic premises that underly Friedman’s argument that capitalism is a necessary presupposition for the existence of political freedom.

—————————————

“Professor Friedman’s demonstration [in _Capitalism and Freedom] that the capitalist market economy can coordinate economic activities without coercion rests on an elementary conceptual error. His argument runs as follows. He shows first that in a simple market model, where each individual or household controls resources enabling it to produce goods and services either directly for itself or for exchange, there will be production for exchange because of the increased product made possible by specialization. But since the household always has the alternative of producing directly for itself, it need not enter into any exchange unless it benefits from it. Hence no exchange will take place unless both parties do benefit from it. Cooperation is thereby achieved without coercion’…So far, so good. It is indeed clear that in this simple exchange model, assuming rational maximizing behavior by all hands, every exchange will benefit both parties, and that no act of coercion is involved in the decision to produce for exchange or in any act of exchange.

Professor Friedman then moves on to our actual complex economy, or rather to his own curious model of it:

As in [the] simple exchange model, so in the complex enterprise and money-exchange economy, cooperation is strictly individual and voluntary *provided*: (a) that enterprises are private, so that the ultimate contracting parties are individuals and (b) that individuals are effectively free to enter or not to enter into any particular exchange so that every exchange is strictly voluntary…

…Proviso (b) is ‘that individuals are effectively free to enter or not to enter into any particular exchange’, and it is held that with this proviso ‘every exchange is strictly voluntary’. A moment’s thought will show that this is not so. The proviso that is required to make every transaction strictly volunatry is not freedom not to enter into any *particular* exchange, but freedom not to enter into any exchange *at all*. This, and only this, was the proviso that proved the simple model to be voluntary and noncoercive; and nothing less than this would prove the complex model to voluntary and noncoercive. But Professor Friedman is clearly claiming that freedom not to enter into any *particular* exchange is enough: ‘The consumer is protected from coercion by the seller because of the presence of other sellers with whom he can deal…The employee is protected from coercion by the employer because of other employers for whom he can work…’

One almost despairs of logic, and of the use of models. It is easy to see what Professor Friedman has done, but it is less easy to excuse it. He has moved from the simple economy of exchange between independent producers, to the capitalist economy,without mentioning the most important thing that distinguishes them. He mentions money instead of barter, and ‘enterprises which are intermediaries between individuals in their capacities as suppliers of services and as purchasers of goods’…as if money and merchants were what distinguished a capitalist economy from an economy of independent producers. What distinguishes the capitalist economy from the simple exchange economy is the separation of labor and capital, that is, the existence of a labor force without its own sufficient capital and therefore without a choice as to whether to put its labor in the market or not. Professor Friedman would agree that where there is no choice there is coercion. His attempted demonstration that capitalism coordinates without coercion therefore fails.”

This essay makes about as much sense as the story

milton firedman would tell. In other words, its not right, or wrong, any more than milton’s, but simply a hypothesis or speculation. Its a speculation about what ‘the truth’ of things and situations is.

Phrasing it as if you, or marx, or socialists, or anybody else has found ‘the truth’ and all that one needs to do now is spread it at conferences and on blogs or in zines I think is the wrong way to go. Workers who are ‘disconnected’ often are actually connected to many things (somewhat like atoms in molecules which often are bonded to many other atoms at once, so they have ‘competing interactions’). So to say they are alienated and exploited disregards their actual relationships and ‘true feelings’.

Rather than proselytize or spread the word about ‘the truth’, I think it would better to create situations where the ‘working class’ can explore the truth. This is almost a group psychology excercize. Unfortunately in this world, psychotherapy is a business only, and for experts. By definition the masses are not experts in psychotherapy (since expertise is rare) . Most have little interest or motivation for such group activity (even less than joining a union or voting). There are other things to do (which one can attribute to propoganda, assuming again one know ‘the truth’ about what people really should care about—-eg politics, or sports, or michael jackson).

I also think socialists commonly basically really don’t give a f-k, and groups like the ISO seem to have a really bad rep, and even in my experience they basically operate like a cult (eg the moonies), pressuring or torturing people into submission to THEIR socialist vision (which is private property, for the public to use based on ability to pay). So, alot of what passes for socialism is really just self-promotion passed off as a public good.

I wonder if this comment will last here, or will be censored, or just ignored (as is common in political debates—silence being seen as the golden goose).

Interesting post Incidentally I had written something to a similar effect recently: http://spiritofcontradiction.wordpress.com/2009/07/07/on-political-stances/

I guess the socialist movement really is needing a what-is-to-be-done type of document, we seem to be very disoriented, or perhaps I project onto the whole movement my personal state of mind. I certainly don’t think doing the same thing we’ve been doing for ages and expecting something different to come out of it is going to give us good results.

From the Macpherson quote:

“What distinguishes the capitalist economy from the simple exchange economy is the separation of labor and capital, that is, the existence of a labor force without its own sufficient capital and therefore without a choice as to whether to put its labor in the market or not. Professor Friedman would agree that where there is no choice there is coercion. His attempted demonstration that capitalism coordinates without coercion therefore fails.”

But wait! Macpherson ignores the fact that labor does have a choice not to put its labor on the market, its called homelessness! 🙂

Ishi,

Being a former member of two different M-L socialist organizations I can share your distrust or discomfort with some of these organizations. But don’t let that stand in your way from appreciating and understanding a Marxist analysis of capitalism. Somehow and someway we are going to need to come up with some different model of socialist organization.

In my experience most Marxists confuse the conclusions of a political analysis with a political programme and a method of politics. They then think that you have to convert people to Marxism, and win them to the Marxist programme. This doesn’t work, it promotes sectarianism and, because they are blinkered by their own ideology, it leaves Marxists saying that the workers are just too backward, stupid or some such thing. But really they are stupid themselves, because after all the fanfare and brouha about how “Marxist” they are, they are left asking, “what do I do now?” and “why don’t they believe me?”. A much better idea would be to unite people around the things they really value, in a culture they believe in, with the opportunity to develop themselves. If you really try to free yourself, change yourself and change the world, you will soon enough learn what the reality is, or be motivated to learn about it. But in truth, few Marxists are interested in real people and their lives. Most of them just have a fascist religious rhetoric about “emancipation” and “struggle” covering up the fact they are really anti-humanist and anti-worker. When there is a quarrel, they stab their own “comrades” in the back, full of righteous moralism. Real people do not fit in the Marxist schema for how world history ought to run. The general level of human intelligence and psychological insight of the American Left is, judging by what they write, so abysmal, that I am not surprised that most people avoid them like the plague in getting on with their lives. As a matter of fact I hardly refer to Marxism anymore myself because most of these Marxists give Marx a bad name. Needless to say, if you deride everything that people value about their lives and where they live, you are not going to be able to motivate them or lead them. Quite simply, people do not want to hear about everything they are doing wrong. I am not American but if American Leftists want to stop being losers, I think they are going to have to do what it takes to win. But they are mostly not even curious to find out and learn about that. It is so much easier to blame the workers, repeat the Marxist formula for the nth time, and tell Iranians how they ought to organise their society.

Mike,

“Nowhere are systematic falsehoods presented as truth more than with respect to the nature of our economic system.”

There is a narrative subtext to economic thought that brightly illuminates the systematic falsehoods. It’s really not all that evident in the writings of Adam Smith, Ricardo, J.S. Mill, J.B. Clark, Jevons or Marshall. It resonates more with the vulgarizations of J.B. Say’s “Law” and with the selective celebration of Bastiat’s “Sophismes”.

The theme of that subtext is that workers are fundamentally ignorant, lazy and gullible and thus susceptible to the influence of a particular sort of “workingman’s fallacy”. Dispelling this alleged economic fallacy thus becomes the civilizing task of economics. One has to experience the persistence of that narrative — and observe, in many instances, the vehemence, the sheer loathing with which it is advanced — to fully appreciate the power that it exercises over the economic imaginary.

It is a libel and fable repeated over and over decade after decade for two centuries — often using the exact same words and phrasing.

Economists tell us that their models rely on “axioms of rationality.” What they don’t say — what they don’t even suspect — is that embedded in one of their more inconspicuous “simplifying assumption” is a rather convoluted exception to those axioms. How that simplifying assumption came to be is a long story but why it came to be can be traced to economists’ complacent embrace of the fallacy mythology for it involves a subtle discounting of workers’ rationality paired with an elevation of the employers’ perspicuity.

It is one thing to flag the systematic falsehoods about the economic system but it is quite another to document how they operate. It is not a matter of a Friedman simply inventing falsehoods but of a trained and habitual receptivity attuned to just those falsehoods. Friedmanism thus must be viewed as a symptom rather than a cause.

Exemplary specimens of this workingman’s fallacy claim can be found in the following texts:

Charles Knight, (1830) The Results of Machinery

Harriet Martineau (1859) “The Secret Organization of Trades,” The Edinborough Review

James Ward (1868) Workmen and Wages at Home and Abroad

John Wilson (1871) “Economic Fallacies and Labour Utopias,” Quarterly Review

Henry Wood (1894) The Political Economy of Natural Law

Charles Buxton Going (1900) “Labour Questions in England and America,” The Engineering Magazine

i appreciate not being censored even if my etiquette is rough (like the music i mostly listen to).

i actually basically agree with your point and farmelant’s quoted analses of friedman. one of my points was to an extent this is like beating a dead horse, and beating a dead horse will not lead thr masses to socialist or other truth, but rather i hypothesize has proven to lead them to turn on the TV, because beating dead horses only has appeal to a small market. (so maybe we could torture cats or something (porn?) to see if it brings in some paying customers, to mrzine or pacifica.) (playboy published james baldwin i think.)

also, those critiques are pretty well known, even to the people who theorized the ideal market economy (debreu, arrow, etc.). the pure free market basically assumes there is no friction or imperfections in human transactions, when it is known that many rocks, for example are not perfectly round nor frictionless like superfluid helium or ice queens. even humans occasionaly have rough edges—eg the sex pistols’ ‘no feelings’ or on my blog backyard’s ‘we dont give a f-k about you, and all your homies gonna get it too’. (Stiglitz goes through this in a recent book—200 pages showing how strong and brave he is at beating a dead horse; i guess it gets you a noble prize so you don’t have to steal. That may be a bit harsh on stiglitz, but then he seems to take financial insitutions as a priori neccesities, which i dont—as michael said, it is the seperation of capital from labor that really is the defining feature. and it permits profit (though as noted according to the theory in the long run, if the model is right, then markets clear so there really is no profit—-maybe we should just give it a time to work?

But, as i said, such a division is like the division of labor, and this is not unique to capitalism. Corn produces food, and humans eat it. Is there any way out of the division of labor? Maybe we need finance. Maybe alienation is neccesary. Same for coercion–its not just capitalism. People coerce plants and animals by using them, for example. Gravity pulls me down. And, in a sense, possibly gravity is not coercive, nor bosses and capitalism’s institutions—-as noted I am theoretically basically agnostic since I dont kn ow if ‘another world is possible’. Of course, as I believe it is possible to raise children without violence, or have development without slavery, i do think another world is possible and wish there could be one. But ‘objectively’ i cannot say it is. (I will also say as a very semi-activist, I often do think ‘the masses’ can be free riders—refusing to lift a finger to liberate themserlves, meanwhile ernjoying the fruits of capuitalism by supporting the forces activists kill themselves fighting, and then, when the struggle is over and the activists dead or burned out, take the new conforts liberation offers. Clarence Thomas might be a sort of stand out example.)

It is true people like friedman and folks at the IMF often ‘vulgarized’ economic theory to pretend what they were doing (neoliberalism) was sound policy, and it did create a right wing industry and cult of groupthink. (people have vulgarized or dumndowned adam smith, darwin, and marx too.) And people like Arrow didn’t raise much if any fuss. But i don’t really think that should be blamed on economics theory, which is just a known first approximation theory. (arrow even wrote something like ‘a cautious approach to socialism’ and samuelson wrote several articles attempting to make a marxist/communist system feasible and theoretically sound even if he didn’t support it). Also, the left not uncommonly develops its own cult and industry, ranging from stalin to some green movements.

Also, i do think that Friedman’s is in a sense as valid an interpretation as Marx. To me, the only difference is one uses profit and sees it as good and also the griver of social progress, while the other uses exploitation and sees it as bad, and leads to social misery, decay or crisis. To me these are just labels. If a 6 turned out to be 9… I even think possibly through redefinitions, you can more or less analyze the world as if it were a free market. (The basic idea here is from physics—-for example a nonequilibrium system such as a moving car can be analyzed as an equilbriumone if you just adopt a mioving set of coordinates, and the same can be done for economics in my view. You just transform out the bounded rationality to a corrdinate frame where everyone actually communicates instantly and perfectly. (This reference frame of course may not be intuitive, but then neither is a curved 4-dimensional spacetime either nor the world of quantum probabilities—so ‘just get over it’.) I do know many people hate that kind of idea—so they promote ‘heterodox’ views which deny the possibility, when in my view those arent heterox actually but just the same ones with different labels. This idea is also called ‘linearization’ or ‘effective field theory’. )

The main problem i have with the quoted remarks is what they leave out—-sure, markets are not perfect, and there is what can be called coercion , explicitly or implicitly. But everywhere there is coercion—you get tired, hungry, are subject to the weather. Culture constrains you. So, capitalisms institutions and rituals are not unique in being coercive. In fact, one can argue that just as we need air, we need capitalism, even if both of these needs reastrict our freedom. (And actually we can choose to do without them—so what you have a huge ‘path dependent’ or ‘supply chain’ of needs and it is hard to know what one really needs—-did we need WW2, and ‘macroshaft’ so we can exchage ideas on a blog? )

also, one can argue people exploit themselves, or volunteer slavery—people gave bill gates the money. (the old article by a harvard prof called ‘what do bosses do’ and other papers i think by bowles and gintis i think explore more the issue of how complicit people are in their enslavement, and even whether—as a dog in a sense can control his or her owner, or a dependent (eg classicaly an unemplkoyed wife) can actually control the provider—-so-called victims or exploitees actually might be the real exploiters (e.g. the low paid slacker versus the CEO who works 80 hours a week; or maybe sex workers who enjoy it and get the people who employ them addicted).

Also My point, or conjecture was that even if you are saying ‘the truth’, maybe that’s not the way to put it across. I sometimes see animals in danger of getting hit by cars or bikes, and I’ve learned if you go at them too hard to get at ‘the truth’ as I define it (which is that i want them alive) sometimes it makes it harder getting them to safety. For example, having left wing radio which is as dogmastic asd right wing radio, I think may just promote co-dependence on sound bites, and sound bites are the problem. People really need to analyze relationships to find where there is coercion and exploitation. (I figured i would get censored, and I have found being ignored and censored such as on blogs or even community disucssions, is basically maybe the number one factor in what i call ‘quiet fascism’ we have now. It enforces group think into narrow ideologies by stifling discussion.

I do think the ‘left’ broadly speaking may need some ‘rebranding’ and new ways of ‘framing’ the issues if they are going to become more than a niche product for a few. (I really don’t know how myself, and am actually now being real open to the idea that actually that small niche is forever just like a little preserved wilderness area, or like the indians, who once basically owned or controled the usa and now are basically on little reservations often not evn their native geographies. in a sense this is why my nom de plume i chose.)

so maybe some more complexity is in order—and possibly moving back from words like socialism, exploitation , profit, etc. i don’t read as much left stuff any more because its gotten inbred a bit and often the same issues are discussed elsewhere in other terms.

also I do know some immigrants who are very aware of how bad in many ways lives are at home see US capitalism as essentially the best of all possible worlds. They may not evedn feel exploited. Or, see that pain as hopefully temporary, and as neccesary as sometimes making children unhappy by disciplining them or denying them so they become strong adults. People may hate their jobs and such, but equally they often love their computer, electronics, travel, cars, bikes etc.

People may hate bill gates, but the left and everyone else essentially is in debt to him for making the web user friendly (and making using people user friendly too). Was there any other way to make the web which many take for granted to be neccesary to modern life? Could the USA have developed without slavery of elimination of indians? who knows, is m view. But sometimes people decide that pain (and exploitation) in the long run is worth the cost, because it pays back in forms of profit. They follow the prophecy of profit, and see the utopian vision of Friedman and general equilibrium at the end of the rainbow. (Don’t lose the faith and keep your eye on the prize.)

——————————-THIS GOT WAY OUT OF CONTROL.

I was going to edit the following to see where it fit in but have given up. i probly should delete it. anyway

‘close to the edge, i’m about to lose my head’.

reARDING ECON, i assume you are referring to the pareto optimality criteria which can be proven to exist (by arrow and hahn) for ideal market economies (perfect information (from prehistory to the infinite future), instantaneous adjument times/no friction). for some of us, that works—but let’s now praise all Us Famous Men. the lessers among equals never get to general equilibrium.

but, as i was saying—maybe capitalism is not to blame, but rather moral luck, or else/also the genes? For example, evolution has designed humans ( to be imperfect (basically its eve—see the bible) and hence they are not perfectly rational, but rather ‘boundedly rational’ as h. simon put it. But evolution is not the fault of capitalism (though some do argue that Darwin actually borrowed his ideas from Adam Smith, so conceivably what is called evolution actually was really just part of a business plan that began with the enclosure movement, proceeded through industrialization, and has now gone into a new set of product developments called ‘genes’ which, as Veblen showed for all products, basically become neccessities. And of course everyone needs to know evolution, too—you cant graduate without it.)

maybe to be clearer, i should say i actually like the 2 welfare theorems of general equilibrium (free market) theory—that markets do clear and reach a pareto optimum, and (my favorite) you can reach any Pareto optimum you want (eg Bill Gates has evertything, and noone else anything; or everyone has the same thing) by a suitable redistribution of initia; endowments (eg for genetic determinists, we just make sure everyone mates with everyone else, or via moral luck, maybe you just make every decision a random choice, so over time everyone gets dealt the same fate.)

John Roemer among others goes through the welfare theorems—he advocates market socialism if i recall.

so capitalism/market economies actually say nothing about who gets what. that depends on the initial endowments (which actually is why libertarians like Herbert Spencer who advocated abolition of inheritance actually were pretty consistant in my view—-that would correct maybe half of market imperfections (or ‘exploitation’/unequal power).

in this ideal formalism, at Pareto equilibrium there is no ‘profit’. everyone gets what they deserve.

that model is just an idealization but these toy models have intellectual interest, and some relevance.

In fact, my main point or critique was neglect of the ‘bounded rationality’ issue. Basically people have finite time, attention spans, have to sleep, are all programmed from birth by parents, peers, culture, etc. That programming can be said to be half ‘truth’ and half propoganda (in, say, the ‘progressive’ sense that people have some universal basic needs, and then also the capacity to become addicted to consumerism, self or other kinds of abuse–including evnvrionemtnL , etc.).

following up on my earlier comment, the following excerpt is from a chapter I’m currently writing:

The notion that there is some sort of economic fallacy basic to the aims and methods of trade unions – or more generally to inchoate beliefs of working people – is a polemic with a long, albeit tortuous, history that goes back at least to the Luddite uprisings of 1811-13 in England and the Swing Riots of 1830-31. An 1830 booklet issued by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, in response to the 1830 incidents, sought to “explain” to ordinary workers the proposition that “the results of machinery” (the title of the booklet) were to cheapen commodities and thus, ultimately, to expand trade and increase employment. Such an explanation presupposed that motives for breaking machines arose from a “misunderstanding” of the nature of machines rather than from rage at desperate economic circumstances and harsh political repression. The supposition sidesteps the likelihood that the underlying grievances were legitimate regardless of whether or not the ensuing destruction of property was either suitable or effectual.

In a 1859 article, “The Secret Organization of Trades,” Harriet Martineau claimed that the aim and object of trade unions was “to stint the action of superior physical strength, moral industry, or intelligent skill in order to protect the inferior workman from competition… in short, to apply all the fallacies of the Protective system to labour.” Martineau’s reference to the fallacies of protectionism echo the sentiments of Frederic Bastiat from a decade earlier, whose satirical treatment of the issue popularized the practice of ridiculing economic fallacies.

In an 1868 treatise on Workmen and Wages, James Ward claimed to have identified “the real cause of the objection to piecework and overtime…” which constituted “the fallacy which lies at the bottom of this whole system [of trade unions].” That fallacy was held to be:

In the tradition of classical political economy, Ward accepted the doctrine of a “wage-fund,” the magnitude of which was given at any particular time. The fault of the unionist was that, without consideration for its source or continuance, “his aim was to get as much out of the wage-fund as possible.” Three years later, John Wilson added a new twist to wage-fund angle by attributing “the enforcement of all sorts of arbitrary restrictions on the combined workmen” to a “Unionist reading of the Wage-fund theory.” In the late 1880s, Alfred Marshall followed in this tradition when he posited the existence of a “work-fund” doctrine analogous to the, by now largely discredited (or drastically revised) wages-fund doctrine.

It would be useful at this point – before moving on to rebuttal – to summarize the vagaries in the fallacy story as it has unfolded over the years. The alleged objectives sought by workers have included resisting the introduction of machinery, piecework and overtime; standardization of wages without regard to effort or skill; and increasing wages without regard to output or market conditions. Meanwhile the alleged error has been to assume that the amount of wages or of work to be done is either constant or will not be affected by the productivity or otherwise of labour. The authors of these fallacy stories display attitudes that range from benign condescension toward the workers to abject hostility toward trade unions to cautious sympathy with both. The implied person who commits these fallacies is either painfully ignorant, negligent or – if rational at all – vicious.

Over the years, labour leaders and sympathetic writers repeatedly disavowed the intention to restrict output and the fallacious assumptions that go along with it. But it would be hard to find a more comprehensive and authoritative reply than the 921 page 11th Special Report of the U.S. Commissioner of Labor on Regulation and Restriction of Output prepared and edited mainly by John R. Commons and issued in 1904. A paragraph in the conclusion to that report neatly summed up why “the question of restriction of output… is not as simple as it has been supposed to be.” Investigators concluded that workers were increasingly insisting that changes in work organization, methods or materials be by mutual consent and this resulted in “restrictions of output” when compared to a hypothetical level that might be attained if employers could impose their efficiency plans at will. It was a simple, clear and reasonable explanation and one that didn’t require any elaborate speculation about fallacious theories or nefarious motives.

Sheldon,

Thanks for comment. I guess all we can do, absent any mass movement that cared about disseminating useful information to workers, is spread the word as best we can and hope for the best. That said, pass along my post to others!

Jim,

Thanks for this. I spent a long time mastering the Friedman arguments in graduate school. Pareto optimality and all that. I was amazed when I studied Marx to see that the whole argument was a house of cards. McPherson’s argument is really clear. Shows that Friedman was nothing more than an apologist.

Ishi,

Thanks for your comments. I don’t ever censor things. I disagree with you about the truth. Friedman’s story is, as McPherson shows (see Jim Farmelant’s comments above), demonstrably false.

I do agree about some of the rest of what you said (BTW, I am not a member of the ISO or any other political organization). When I teach workers, I do not proselytize. Rather, I try to start from their own experiences and build up to some general principles. This is really the only way to do it I think. I have to say that workers typically think that the Friedman argument is insane. They usually like Marx’s argument better, no doubt because it accords so well with their experiences. Still, though, like you say, workers are more than workers; they have many other aspects to their lives. No argument an capture the whole truth of existence.

You might not know that in the Friedman (neoclassical) argument, the distribution of wealth (property) is taken as given. That is, the best they can say is that under extremely rrestrictive assumptions, in market equilibrium, no one can be made better off without another being made worse off, GIVEN THE DISTRIBUTION OF INTITIAL ENDOWMENTS.

David,

Thanks for your comments. I read your essay and found it enlightening. But in teaching workers, I often find a good deal of receptiveness to Marx’s analysis of capitalism, if not to his ultimate conclusion that capitalism has to go. One reason to keep the flame of Marx burning is that history throws up circumstances that can least to radical changes. Then, it is good for some at least to have their bearings. The secular radicals in Iran, including the Tudeh Party (Iranian Communist Party) made very costly tactical errors, throwing in with Khomenei, when they might have done otherwise. Lenin, on the other hand, made no such errors in 1917. What if US labor had not made incredible errors over the years, if it had, for example, defied the Taft Hartley ban on communists?

Anyway, I appreciated your essay.

Tom and Jurriaan,

Thanks for the erudite comments! Tom, Adam Smith too seemed to think poorly of workers. He loves the detailed deivision of labor, says it makes people as stupid as it is possible to be, and then recommends education in “homeopathic doses.”

Jurriaan,

In my labor education work, I have a lot of experience with all sorts of things ordinary people are interested in, from sports to religion to music and travel. You have to start with people’s experiences and have plenty of your own.

Thanks for your continued engangement on the class conscious side of the struggle for more freedom, FW. I especially enjoyed the references to the IWW Preamble and the appeals for clarity about where we are and where we need to get to in order to get off this toboggan ride to destruction aka Capital. I mean, the glaciers of the world are melting and our rulers are hemming and hawing about how to deal with climate change without losing a buck or two in the process. Talk about incompetence! Of course, cover it all up with a few verbal sops to Africa so the liberals remain quiescently tied to the marketplace for commodities.

What can we do? Joe Hill said it best, “Oraganise”. And he was talking about organising as a class to begin to the form the new society within the womb of the old one and, of course, abolishing the wage system in the process. The tactics of getting to a more democratic, relaxed set of social relations should most definitely be focussed on shorter work time; but not the kind the cappos want to impose, the kind where they drive down the standard of living of the working class in order to ‘solve’ their problems with the rate of profit. But, that kind of free-time can only be won if it is backed up by class conscious, democratic unionism, unionism based on the notion that the wage system is inherently exploitive, life damaging, alienating and anxiety creating. Well, that’s one Wob’s opinion anyway. ;p

Mike wrote:

“You might not know that in the Friedman (neoclassical) argument, the distribution of wealth (property) is taken as given. That is, the best they can say is that under extremely rrestrictive assumptions, in market equilibrium, no one can be made better off without another being made worse off, GIVEN THE DISTRIBUTION OF INTITIAL ENDOWMENTS.”

and Ishi after having earlier suggesting that this discussion was “beating a dead horse” then later on proceeds to not only to keep kicking the deceased animal but to go on to excursion with the social welfare theorems as developed by the neo-Paretians (BTW a summary of which can be found at:

http://homepage.newschool.edu/het/essays/paretian/paretosocial.htm).

In fact it is probably not such a useless exercise because this points out that modern welfare economics does not necessarily support the conclusions that Friedman and his followers have wished to derive from it. As Paul Samuelson has often pointed out to derive the conclusion that any given Paretian optimality is also socially optimal we have to assume that the distribution of initial endowments was ethically acceptable. Such is not necessarily the case from the standpoint of either a utitlitarian ethic or a Rawlsian ethic.

Ishi mentions John Roemer, but most of Roemer’s points were made long ago by the Polish Marxist/neoclassical economist Oskar Lange, who likewise was an advocate of market socialism. (Lange’s position was that to understand how capitalist economies actually work, we have to turn to Marx, but to understand how to properly manage a socialist economy, then we have to turn to neoclassical economics).

i am familiar with lange and lerner (have read them—-even own some stuff of theirs) and was aware that roemer was basically rehashing his ideas (using what i consider to be a messy math formalism, since there are others i find easier). (he didn’t get market socialism, but got to yale from davis, which i think actually may be the primary use of marxism and socialism these days, apart from the low brow version of an ISO church rally). (i think stiglitz also has a version of this).

my mentioning the welfare theorems was basically to say the same thing as you—-they don’t support any particular pAreto optimum (distribution of income) so mike’s bringing them up does not support friedman really (who didn’t deal with initial conditions, which is also the problem with people who rely on coase’s theorem usually).

and i was criticizing some self-styled ‘heterodox’ economists who basically ignore this point and either beat dead horses about economics (or rather beat what they call a horse, even if its a rock, and look like they are killing it, like a brave and perceptive bullfighter.)

intellectual excercizes (possibly like physical, or creative ones) are fine—they ‘build strong character’ (eg john wayne—the bands MDC (hardcore) and JYB (gogo) both have good songs about john wayne; ishi and him are sortuh similar, like the proton/antiproton pairs). the connection of them to, say, ‘disconnects’ in minds and social realities is a difficult topic (though maybe I can get tenure at Yale doing its ‘cognitive bias’ and values project—-you know, do polls on the great martin luther ‘rodney’ king question ‘why Kant we all get along?’ Perhaps its categorical impariment?

write me a ref? or a cv?)

as i mentioned in my earlier excessverbiage/shakespearian classic blog post (already living forever out in the universe and being read by other plan-its), intellectual excercizes (such as social group therapy of some sort (think the federalist papers and const conv (constituional convention, or the convention that the speed of light is a constant—same difference) ) maybe if instead of prostelytizing using outdated slogans like at patriot rallys or promise keepers, people talked a bit about ‘pareto optima’, or even just welfare or justice, then some mental disconnects might be repaired along with the social. as i noted, this may be impossible (due to initial conditions) so maybe my choice fior epitaph will be an epithet, to keep in the spirit of the times. ‘the change—we need.’ (or for big thinkers, there’s biggie smalls’ ‘gimme the loot’.)

obviously the real intellectual excercize is to figure out how much the perfect information and rational self-interest assumptions need to be altered, to get beyond an ideal gas or perfect mechanical model of economic exchanges (and others). you need condensed matter physics, etc. i actually have an idea about how to do this, as illustrated above. and as noted, for another intellectual excercize you can then transform the imperfections out so Leibniitz (of candide) will be satisfied should his wave function encounter this blog post.

Mike…

Marxists are no better or worse people than anyone else, some of them are indeed very interested in people’s lives, but I think we ought to look more carefully about how their theories are actually formed and what the proper function of theorising is, what role it ought to play. To my knowledge none of the great Marxists regarded the working classes as one homogenous heap. Every social class has its leaders, its advanced thinkers and doers, its movers and shakers, its conservative and progressive groupings, as well as its more backward elements. Obviously if you focus on the worst elements of a social class, those who are least socially and politically aware, then you are going to develop a rather pessimistic idea about what’s possible. But why should you do that? Why not try to be in the social vanguard of your society? Marxists often regard Marxism as a philosophy, but Marx & Engels themselves thought that philosophy was largely supplanted by science and empirical-practical verification. Gramsci is probably closer to the mark with his idea of a philosophy of practice, i.e. a viewpoint developed out of the conclusions drawn from experience that guides practice. But this suggests really a process of learning by doing, rather than a rigid adherence to an authorative doctrine, in which our own creativity and experience is just as important as what our predecessors contributed.