In the August 14, 2009 New York Times there is an article about Albert Perdeck, an eighty-four year old veteran of the Second World War who has never fully recovered from the trauma of having the aircraft carrier on which he served in the South Pacific struck by a Japanese kamikaze attack. He still has nightmares, and he has been troubled by an undefinable anger for more than sixty years. He can smell still the smoke and the charred bodies.

Such accounts by old veterans sadden me and always remind me of my father, whose life was so shaped by his time as a Navy radioman in that same South Pacific war. He didn’t experience as much violence as Mr. Perdeck and was not so emotionally scarred, at least as far as we knew. He’d get angry, especially when anyone denigrated the United States or when the government didn’t take care of its veterans. He once chastised me for not respecting the flag. The silkscreen I had of Chairman Mao didn’t please him, to say the least.

My father would have been eighty-seven this past August 8. He was born exactly twenty-three years before the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. What follows is an excerpt from my book, In and Out of the Working Class. Consider it a remembrance, dad.

“Bud: My Father”

Bud’s feelings toward his father Carl were ambivalent. He admired his father’s abilities. Though Carl had quit school in the eighth grade, he had become a time-study engineer at the plant. He could add long columns of numbers in his head and he could tell time without a watch. He had been a skilled athlete, a long-distance runner and a baseball player. He used to take Bud to the local games; Bud remembered yelling “that’s my dad” when Carl hit a home run. His father’s best sport was bowling. He was the best bowler in town, and he almost never missed a spare. Bud was a good bowler himself, the one sport besides pool he could play well. His high school yearbook had commented that “he could give his dad a run for his money” on the lanes. But he wasn’t as good as Carl, and that was the problem. He felt that his father didn’t respect him. Maybe it was because Bud had been sickly when he was a baby, with tubercular bones that had cost him two years in a sanitarium. He still wasn’t strong, and he never could play baseball or any of the rougher sports. He sure wasn’t much of a fighter.

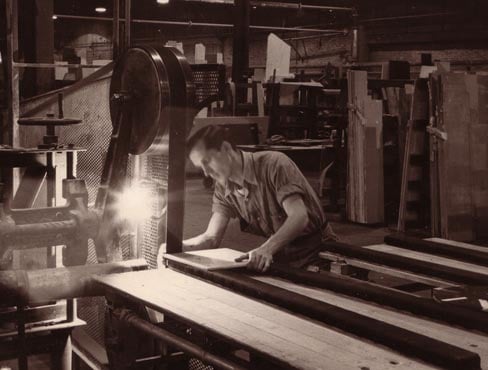

The one thing Bud did have over his father was that he had been in the War. He had enlisted in the navy right after Pearl Harbor. He had graduated from high school in 1940 and, with his father’s help, started to work in the factory, packing glass into crates for fifty cents an hour. He hadn’t liked school much; what was the point of studying when you could hang out with the guys. Working and earning a paycheck were all right, though the work was monotonous. He had been to a CCC camp two summers before, so he was used to getting up early and working hard. He wasn’t a troublemaker or a loudmouth, and that helped too. Most of his classmates were either working or had turned in applications, so he had friends at work, which was nice. It was strange at first, going through the long tunnel and into the enormous plant, punching the time clock and getting to work. He had started at the south end, where the unskilled assembly work was done, but he hoped to get a better job, maybe in one of the shops or at the north end where they made the specialty glass. Right before he had started to work there, the men had organized a union, and now they didn’t have to take all the crap the foremen had handed out before; at least, that’s what the old-timers told him. He had heard more than a few unkind comments about Carl from the men, though they had a grudging respect for his athletic skills. But they didn’t like his stop watch, timing their every move and motion, always trying to make them work faster and harder. Carl was a “company man,” something Bud could not afford to be. For his father it was “PPG this and PPG that.” For him, it was just a job, though he couldn’t see why you shouldn’t put in a good day’s work for your pay.

Everyone in the town had been talking about war. It sounded exciting, a chance to get away and do something different. Almost every guy he knew had enlisted. Not only had he joined the Navy, but right after boot camp, he married his high school sweetheart. Irene had lived with her mother Lucia during the war and made a little money working in the company store. Everything boomed then; he remembered the crowded streets and bars the one time he went on leave before shipping out. Some bastards had made a lot of money, cheating the servicemen by raising their prices. Bud hated people like that, guys who’d get ahead whatever the cost. After boot camp, he went to radio school in Chicago. Some nights he had guard duty in front of the Chicago Stadium. Only later did he learn that inside, people were helping to develop the atomic bomb that had finally brought him home.

The war had been an experience like no other. Young guys thousands of miles from home, boys like him, from all over the country. He had been in the Ellice Islands in the South Pacific for two years. He remembered the odor of the bodies piled up on the beach of the island on which he was stationed. You could smell them from 10,000 feet up in the plane; it was a smell that stayed with him still. Later, he watched U.S. marines pick the gold out of the dead men’s teeth before they were dumped into mass graves. He remembered getting bombed every night; one of his bunk mates had been hit in the middle of the night without him even knowing it. The radio operators listened to Tokyo Rose, and she would tell them that they were going to be hit that night. She “interviewed” American prisoners of war, and one night he heard the voice of a soldier from his hometown. He wrote back to his wife to tell the parents that their son was alive. He never made better friends than his buddies in the war.

When he got back home, he returned to work. He lived with his wife and Lucia for a year. That had been awful, with no hot water and an outhouse, not to mention the coal smoke and foul air. After their son was born, they moved to a small house on a farm, closer to work but still a long walk and still an outhouse. The excitement of the war had made it difficult to go back to the factory. You just didn’t want to take any shit from the boss after you had seen so much death. The war had made him and his buddies men, and they wanted to be treated like men. There had been confrontations and strikes, but now at least it looked as though the company had learned that it couldn’t run them over. The war had changed his view of Carl a little. His father hadn’t been there and done what Bud had done. And his parents hadn’t been so nice to his wife, either. They’d actually sold the car he’d bought right before the war and kept the money. His car and his money!

What kept him going was his own family. All through the war he had sent pictures of babies he’d cut out of magazines back home to Irene. Now he was a father. Now he wanted things, so his family could have a good life. He wanted lots of kids, too. He had begun to do a little planning. It didn’t look like the Depression was going to come back. Work was steady; you could put in a lot of overtime. Funny, he had told Irene that he was working overtime when, instead, he had been playing cards for money after work. She caught him, and that ended that. Well, he’d take the overtime and put a little money aside. The government was giving low-interest mortgages to GIs, and he was thinking about building a house on a hill above the town. People said he was crazy to take such a risk, but he thought that it would be worth it to have a place of his own, with a big yard for his kids to play. A house with indoor plumbing and a fireplace; that would be something. Maybe he would take a correspondence course and go into radio repair. He was a radioman, after all; he knew about radios, and everybody had one. He had bought a used Hallicrafter shortwave in Texas where he was stationed when he left the South Pacific. He could practice on that. He would make everyone, including his father, see that he was no ordinary guy.

How I love that story – those personal stories are some of your very best writing.