The drive from Zion National Park to Capitol Reef National Park is spectacular. Almost every road in southern Utah has been designated a “scenic byway,” or for unpaved roads, a “scenic backway.” The landscape changes radically once you drive through the Mt. Carmel tunnel and out the East Entrance to Zion; the dramatic sandstone cliffs of the park give way to flatter ranch lands. Since the change is so startling, I recommend that you enter Zion from the east rather than from Interstate 15 as we did. As is true for so many national parks, the land surrounding them gives no indication of what is in store for the visitor a few miles away. About twenty miles east of the tunnel, you arrive at the intersection with Highway 89, which traverses the Great Valley, a wide swath of relatively fertile land between rocky hills and cliffs. Springs, creeks, and the Sevier (pronounced “severe”) River allow more ranching and farming than is otherwise the case in arid southern Utah (Mormons have a well-deserved reputation for farming in inhospitable outposts, but they also had more water available that a casual observer might think and they relied upon techniques like irrigation ditches first employed by Indians). Between the intersection and the turnoff at Utah 12 to Bryce Canyon National Parks is the town of Orderville. Today the population is about 600, and there is nothing that distinguishes the place to the eye. But late in the nineteenth century, Orderville was a communist society, established by order of Brigham Young, under the direction of the United Order. I discussed Orderville in a previous post, and I refer you to that. There were other egalitarian communities in Mormon country, in both Utah and Nevada. The short-lived United Order community of Bunkerville, Nevada (near the cheap-motel gambling mecca of Mesquite) is the birthplace of the writer Juanita Brooks (1898-1989). Brooks, the granddaughter of a Mormon pioneer, Dudley Leavitt, went on to write the first in-depth history of the Mountain Meadows massacre of 1857. Leavitt may have participated in the infamous massacre, although this has not been definitively established.

We stopped briefly at Bryce Canyon; it would have been criminal not to rest for awhile and look at the hoodoos. Unlike the lodge at Zion, the Bryce Lodge closes in late fall. Bryce’s winters are harsh and snow-filled, while Zion’s are much milder. From an overlook, we could see cliffs in the distance that would some day in the far-off future look like the fantastic rock shapes of Bryce Canyon.

Back on Utah 12, we soon entered some of the country’s most desolate territory. This land, much of which is in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, is where Everett Ruess disappeared in 1934, near the town of Escalante. In his last letter to his family, Reuss wrote: “As to when I shall visit civilization, it will not be soon, I think. I prefer the saddle to the street-car, the star-sprinkled sky to a roof.” Just this year, an old Navaho man told his granddaughter that he had witnessed three Ute Indians killing a white man close to the place where and at the time when Ruess was last seen. The Navaho buried the dead man, leaving behind his saddle, on which he had gotten some blood. The woman told her brother, who found the place their grandfather remembered and found a skull. The remains of the body were eventually sent to scientists at the University of Colorado, who, using sophisticated DNA analysis, concluded that the body was almost certainly that of Ruess. Ruess’s relatives were happy that the mystery of Everett’s disappearance had finally been solved and that his body could finally be put to rest. Not long after, however, Utah’s state archeologist examined the bones and concluded that they were probably those of a Navajo man. Ruess had had dental work, and the skull showed no such work. The Ruess family contacted the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Rockville, Md., and the remains were then subjected to new DNA testing, which concluded that they were indeed those of a young Navajo. The University of Colorado researchers have since figured out that their procedures were flawed. So Everett Ruess is still out there, somewhere in the Utah wilderness. Whenever we are in this country, we think of Everett Ruess and wish that we had been as adventurous as he, that we’d come here when we were young. Edward Abbey wrote a touching poem for this wanderer in the desert rocks and canyons:

A Sonnet for Everett Ruess

by Edward Abbey

you walked into the radiance of death

through passageways of stillness, stone, and light,

gold coin of cottonwoods, the spangled shade,

cascading song of canyon wrens, the flight

of scarlet dragonflies at pools, the stain

of water on a curve of sand, the art

of roots that crack the monolith of time.

you knew the crazy lust to probe the heart

of that which has no heart that we could know,

toward the source, deep in the core, the maze,

the secret center where there are no bounds.

hunter, brother, companion of our days:

that blessing which you hunted, hunted too,

what you were seeking, this is what found you.

It wasn’t so long ago that travelers had to avail themselves of dirt roads and wagon paths to get from place to place here. Utah 12 between Escalante and Boulder was paved only in the 1930s; even today, 12 is the only paved road that takes you through the Grand Staircase. This area was the last mapped part of the continental United States. The Escalante River was the last mapped river, and the remote Henry Mountains, much-loved by Abbey, were the last mapped mountains.

The ubiquitous John Wesley Powell was involved in this, as he was in nearly every aspect of the early Anglo settlement of the west. On his second trip through the region (his first being his heroic voyage through the Grand Canyon), he named the Henry Mountains, for Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian. His brother-in-law, Almon Thompson, did the first surveying of this last frontier, and Thompson’s wife Ellen (Powell’s sister) collected botanical specimens. A pretty impressive crew, all holed up in Kanab, a Mormon town close to the Arizona border that later gained fame as a setting for movies and televison shows, including Stagecoach and Gunsmoke.

A few mile east of Escalante, Utah 12 tacks north toward Boulder, eventually gaining elevation in the Aquarius Plateau, the most striking features of which are Boulder Mountain—more than 11,000 feet—and what has to be one of the largest stands of aspen trees in the country. Our dream is to see these trees in the fall when they must be sensationally yellow and red, or even is summer when their cool green must lend a fine contrast to the pines and rocks. The highway meanders up and down the plateau until finally dropping down into Torrey at the intersection with Utah 24.

Torrey can hardly be called a town; it’s just a few houses, a couple of churches, a library, and tourist-related businesses to service the visitors to Capitol Reef National Park. In November, it is nearly deserted, but the weather is usually still pretty good. Ideal conditions for cheap motel rooms and hiking in peace. We got a full suite at the Best Western for $55 a night, taxes included! The view of the multi-hued cliffs from the back window was by itself almost worth the price. We spent the next four days taking hikes and enjoying the scenery. One afternoon, we went to the nearest grocery store, which is about twenty miles northwest of Torrey, in Loa. Loa has a population of a little more than 500 so the store isn’t very well stocked—though prices seemed inordinately high. Loa got its name from a Mormon missionary who had been sent to convert the natives of Hawaii. There is a storage company in town named Mauna Loa Storage. I read that some Hawaiians actually came to Utah to settle after having embraced the Latter Day Saints. What must they have thought when they got here?

We mainly go to Loa to see if there have been any noteworthy changes in the area. The towns are so small and ugly that it is hard to imagine living here. Besides Loa, there is Teasdale, Bicknell, and Lyman, all surrounded by farms and sheep ranches. Only rarely do you see a handsome house. No thought at all seems to have been given to even rudimentary landscaping; many houses simply abut the crude streets, and yards have been eschewed in favor of gravel. This year, people looked poorer, and the towns more depressing, perhaps signs of the difficulties most are facing after two years of economic disaster. We always wonder what residents do for a living in these out-of-the-way places. Some are farmers and ranchers, and these enterprises hire workers. Farm and builders’ supply stores, feed stores, and other retail outlets that serve agriculture account for some employees. There are a few doctors, nurses, dentists, and other health-related personnel. Hospitality employees are needed for motels, bed and breakfast establishments, and restaurants. The national and state parks and lands must have rangers and caretakers. The automobile sector (used cars and trucks, repair garages, gas stations, car washes), hardware, drug and other stores, banks, public and religious schools, and other small-town commercial businesses need workers. We met a woman on a hike in Capitol Reef who told us that there were five drug and alcohol rehab facilities in the area, and these must absorb a significant fraction of the workforce. It is not uncommon to find such places in remote areas, the idea being, I suppose, that substance abusers will do better removed from most social contact. Utah is apparently the national leader in overuse of painkillers, so there could be a ready-made in-state clientele. We have also seen a good many alternative schools for “troubled” youth in places from which it would be difficult to escape, for example, twenty miles or so down a dirt road in the dry hills of Wyoming. In fact, there is a youth academy in Loa called the Aspen Achievement Academy. Karen and I are glad that we never behaved so badly that we were sent to Loa.

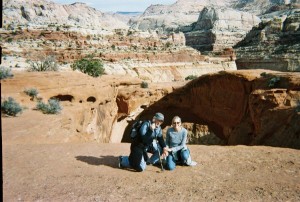

There are many fine hikes to take in Capitol Reef. The land here was formed by an upheaval of the earth along the one-hundred mile “Waterpocket Fold,” now eroded by water, wind, and ice into canyons, cliffs, and monumental white sandstone domes or “capitols” (early explorers were reminded of the dome of the White House). To frontiersmen, some of whom had been seafarers, the Fold seemed like an impenetrable reef. Hence the name, Capitol Reef. The difficulty in penetrating the nooks and crannies of the canyons made this an ideal refuge for bandits. There is a nice hike to an arch (see photo) named after the famous outlaw Butch Cassidy. Cassidy (born Robert Leroy Parker, son of English and Scottish Mormons, who walked across the plains and mountains to Utah attached to handcarts) was part of a notorious gang of criminals, including Harry Longabauch (aka the Sundance Kid), known as the “Wild Bunch.” These bank and train robbers hid along the Outlaw Trail in Wyoming and Utah, which included Robbers’ Roost in southeast Utah, not far from Capitol Reef. No lawmen ever got into the Roost, proof of the remoteness and harshness of the terrain, as well as the fear that these crooks instilled in everyone except the farmers and ranchers who eked out a living in the outback.

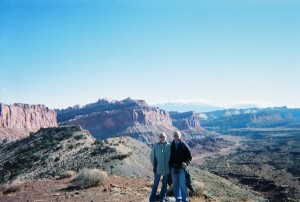

If you have time for only one hike, we think that a good bet is Chimney Rock/Spring Canyon. This can be a very long hike, and the entire Spring Canyon trek can take a few days. But you can tailor your walking to your time limitations. Traveling west from Torrey on Utah 24, you come to the Chimney Rock trail head on your left, a few miles into the national park but before the visitors’ center. There is a parking lot where the trail begins. You head up a slope and continue on it until you reach the top, overlooking the chimney rock, which, as the name implies, is a freestanding rock formation that looks like a primitive chimney. From here, there is a good panoramica view Capitol Reef (see photo) and Boulder Mountain.  Most people continue the hike to make a loop back to the starting point, but a better option is to turn off the loop part way down the hill and head toward Spring Canyon. You will most likely be alone from here on, and if you want a long hike, it is possible to follow the canyon all the way to the Fremont River on Highway 24. If you do this, it is wise to have someone waiting for you with a car at the road. We just go as far into the canyon as we like. There are breathtaking cliffs, many side canyons, amazing desert varnish, Swiss cheese holes in the rocks, water(sometimes) from springs, trees, bushes, flowers, deep sand, and ravens sailing through the wind currents. There is something both supremely serene and foreboding here. The quiet envelops you, as if you were the only person on earth. But the helter-skelter pattern of fallen boulders, the ominous cracks in the rocks, the odd angles of some of the cliff walls, the softness of the sandstone, all tell us that the earth was made in chaos and will continue to be randomly shaken by cataclysms indifferent to human beings. Karen says that this canyon makes her think of the earth when it was young. Young and rambunctious. It is a place we always hate to leave. Go there if you can.

Most people continue the hike to make a loop back to the starting point, but a better option is to turn off the loop part way down the hill and head toward Spring Canyon. You will most likely be alone from here on, and if you want a long hike, it is possible to follow the canyon all the way to the Fremont River on Highway 24. If you do this, it is wise to have someone waiting for you with a car at the road. We just go as far into the canyon as we like. There are breathtaking cliffs, many side canyons, amazing desert varnish, Swiss cheese holes in the rocks, water(sometimes) from springs, trees, bushes, flowers, deep sand, and ravens sailing through the wind currents. There is something both supremely serene and foreboding here. The quiet envelops you, as if you were the only person on earth. But the helter-skelter pattern of fallen boulders, the ominous cracks in the rocks, the odd angles of some of the cliff walls, the softness of the sandstone, all tell us that the earth was made in chaos and will continue to be randomly shaken by cataclysms indifferent to human beings. Karen says that this canyon makes her think of the earth when it was young. Young and rambunctious. It is a place we always hate to leave. Go there if you can.

And if you can’t, listen to the Shaker hymn. Think of the most peaceful and beautiful place in which you have been. Some day when you are too old to drive and too infirm to hike, a special person will take you there. You will lie down and look up at the bluest sky you have ever seen, high above the cliffs of rust and pink, and brown. And you will be glad that you lived.

Your descriptions are so beautiful – I can close my eyes and see it.

Thanks, Toni!