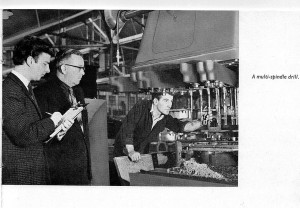

V. A factory is a battle zone. Nothing better illustrates the slogan that “time is money” than the daily struggle between workers and bosses to squeeze a little more free time or a little more work out of the workday. The time study guy would sneak around with his stopwatch, ever on the lookout for a motion to be saved so that another fraction of a second of work could be added to the daily grind. The men watched for him and devised ingenious ways to pretend to be working. If you could start working at 8:02 instead of 8:00, take an extra three minutes for lunch, or line up in front of the time clock a few minutes before the shift ended, you’d beaten the system. Same thing if you lingered in the toilet stall reading the newspaper. A minor injury that sent you home early with a full day’s pay was a sublime victory. If the boss had you do something forbidden by the contract, you licked your lips in anticipation of the grievance you’d file and the backpay you might win. Some guys had learned how to do two jobs along the assembly line, theirs and their buddies, and each would relieve the other for as long as half a shift. This worked especially well when the foreman was in a meeting.

V. A factory is a battle zone. Nothing better illustrates the slogan that “time is money” than the daily struggle between workers and bosses to squeeze a little more free time or a little more work out of the workday. The time study guy would sneak around with his stopwatch, ever on the lookout for a motion to be saved so that another fraction of a second of work could be added to the daily grind. The men watched for him and devised ingenious ways to pretend to be working. If you could start working at 8:02 instead of 8:00, take an extra three minutes for lunch, or line up in front of the time clock a few minutes before the shift ended, you’d beaten the system. Same thing if you lingered in the toilet stall reading the newspaper. A minor injury that sent you home early with a full day’s pay was a sublime victory. If the boss had you do something forbidden by the contract, you licked your lips in anticipation of the grievance you’d file and the backpay you might win. Some guys had learned how to do two jobs along the assembly line, theirs and their buddies, and each would relieve the other for as long as half a shift. This worked especially well when the foreman was in a meeting.

As Clyde wandered around the plant inspecting the safety stations and selling football sheets, he watched the wars play out in each department and listened to the men bitch about the company, and often enough, each other.

“Hey, Clyde, your old man comes down here again with that stopwatch and I’m going to smack him.”

“Hey, Clyde, how come you’re the only white motherfucker comes down here? Only us niggers in the foundry. Man, the Steelers are a lock this week. Same for the Browns. Give me some sheets.”

“Clyde, those niggers’ll be up here soon. Mark my words.”

“Clyde, tell those union guys to stop sipping free coffee in the fire hall and get down here and tell this fucking foreman he better check those machines. Someone’s going to get hurt soon.”

“Clyde, they’re screwing up my incentive pay every week.”

“Clyde, these sonsabitches want me to OK bad glass. Fuckem, I won’t do it.”

“Clyde, we’re going to walk out they keep speeding up the line.”

Back at the fire hall where the firemen sat around drinking coffee and gossiping when they weren’t doing daily chores or called to some emergency, Clyde heard the local unions officers who came by every day for the free joe do the same. Clyde and his buddies told them the things they’d heard, and between the firemen and the union chiefs, there wasn’t much that went on in the factory that went unnoticed. The plant manager always seemed surprised that the union knew things it wasn’t supposed to know.

Like most of the men, he went to the union when he had a problem. Some guys were interested in running the union; this was what they did, like he played the ponies and sold football sheets. He knew little of the sitdown strikes that had spawned the CIO and nothing of the wobblies and Joe Hill. He read in the papers about all the communists in some unions, and he’d heard his dad badmouth the unions often enough. He neither loved nor hated the company. He was mad when his father had time studied him but mainly because it seemed like a betrayal; his old man’s loyalty to the company trumped his loyalty to his son.

One thing kept bothering Clyde though. He couldn’t get the look on Ed Smolen’s wife’s face after the accident out of his mind. On the return drive from the hospital that day, Clyde had recalled a conversation in the fire hall with the union vice president. The union safety committee had warned the company more than once about that crane. The foreman had promised to have it inspected and overhauled but never did. Now Ed’s body was mangled. “Jesus lover!” Clyde had said to himself.

Ed Smolen didn’t die, but he never walked again. He got workers’ compensation, and his family got a harder life. When Clyde kept talking about Ed and the accident, one of the firemen said, “If you’re so concerned about what happened to Ed, why don’t you start going to union meetings and do something about it.” A couple of months later, Clyde did. As he listened to the committee reports, his head got heavy and he started to daydream. Maybe this was waste of time. Then after the safety committee chairman spoke, a man in the back of the room shouted, “What about that crane that crippled Ed Smolen?”

“We’re on that,” said the union president.

“Not fast enough. It’s still not been inspected. Somebody else got to get hurt before we do something?”

The meeting erupted into a shouting match, with Ed’s workmates yelling at the union brass and the union president trying as best he could to defend himself. In the end, the workers agreed that a delegation from Ed’s department would go unannounced the next day to the plant manager’s office and demand some action. Clyde hung around after the meeting talking to the guys about the trip to the hospital and how afraid Ed’s wife had been. He even sold a coupe of football sheets. To everyone’s surprise, the crane inspector showed up at the start of the 8 AM, before the men gathered to confront the plant manager. They went anyway.

Clyde seldom missed a union meeting after that. Within a year, he was like a convert to a new religion—more committed and fanatic than those who had been faithful all their lives. Everything was seen in a new light, and the embers of his class awakening became a fire. He started to argue with his father. When his dad said over dinner that Ed probably wasn’t following proper safety procedures when he was hurt, Clyde swore and left the table. Clyde still sold his betting sheets, but now he came with a message. Don’t trust the company. Support the union.

VI.

Clyde volunteered for the union safety committee, and a year later he was elected its chairman. A year later, he was elected chief union steward. After the president, this was the most important union office. A steward was the union’s first line of defense in the plant, the man who brought new workers into the union, informed workers of their rights under the contract, submitted, investigated, and fought grievances. As head steward, Clyde could go anywhere in the plant at any time to perform his duties.

Some stewards waited for members to come to them with complaints; then they would investigate them; try to settle matters amicably with the foreman; and file a grievance as a last resort. Clyde was aggressive. He met regularly with men and women in all departments, looking for problems and encouraging grievances, the more the better. He wasn’t above threatening a foreman with a work slowdown or four flat tires to get a problem resolved. The grievance procedure was structured as series of steps: informal meeting with a foreman, formal grievance and meeting with the department head; meeting of the plant-wide grievance committee with the plant manager’s staff; and if these failed, arbitration, in which a neutral third party, selected by company and union, decided whether the grievance had merit or not and assessed the penalty against the employer if it did. Clyde loved the sit-downs with the plant manager’s labor relations staff. He was always better prepared than they, and he relished showing off his knowledge to the other stewards and union officers. They’d go back and tell the men how he’d put it to the company. Clyde also led the union in arbitrations. He learned how to prepare witnesses and examine them. The union’s attorney said he’d never seen anyone better. When Clyde pushed a grievance through arbitration, the union usually won. People began to say that Clyde would make a good union president when the old incumbent retired. Clyde didn’t discourage such talk.

The bosses don’t like a good union man. They can deal with the ambitious bureaucrats, the compromisers, the glad-handers. But the guy who goes for the jugular every time, who sees each grievance as a struggle of good against evil, well, that’s another matter. Out of deference to Clyde’s father, the company tread softly at first. They asked his father to talk to him. When this failed, they suggested to his dad that Clyde might make a good supervisor. Clyde told his father that he couldn’t be bought. The men had rights under the contract, and he intended to see that they were upheld. He reminded his father that about half of the grievances were for company safety violations. Maybe if the company was as concerned about safety as it was about bribing him, he wouldn’t have to file so many grievances in the first place. And maybe if the company cared about men not getting maimed and cut, Ed Smolen would still be walking. Clyde’s dad lit a cigar and said, “Clyde, it might not be a good idea to get so radical.”

A few weeks after his father’s talk, the fire chief called him into his office. Clyde thought maybe they were going to discuss some complaints the firemen had made about overtime and shift changes. But when he saw the head of labor relations seated in the big leather chair next to the chief’s desk, he knew something was up. The chief told him to sit down. He did, and the labor relations guy, Art Bowser, started to talk to him. He sounded like he was reading from a script. “Clyde,” he said, “I’m sure you’re familiar with Article Nineteen of the contract.” Clyde said, “Yes, that deals with discipline and discharge.” “Right,” said Art, “We have a situation with someone committing an illegal act while on company premises and during work time.” Clyde thought, “Shit, some asshole came to work drunk.” The agreement said that anyone obviously inebriated could be summarily discharged. Clyde had dealt with three drinking discharges so far, and each time the company had agreed to lessen the penalty to a three-day suspension. None of the cases had gone to arbitration. Clyde said, “Did someone come to work drunk again?” “No,” said Art, “This time someone has been running a gambling racket.” Art looked at Clyde and said, “You’ve been selling football pool sheets, collecting money and making payouts for months, haven’t you Clyde?” Clyde’s saw what was coming. Payback for filing all those grievances. But he smiled and said, “Sure, quite a few of your guys buy tickets every week.” Art said, “We’ve already fired six foremen, just today, for illegal gambling. When we find out who else has been involved, we’ll fire them too” Clyde said, “I want a union rep present. Now.” “Sure,” said Art. He motioned to the chief to bring in the grievance man from the fire department. The chief made a call and in a few minutes the rep arrived. An hour later, Clyde was escorted through the gate and onto the street by a company security guard.

Clyde’s wife cried when he told her what happened. “I told you not to get involved in that stuff with the union. Now what are we going to do?” Clyde said, “Fuck the company. We’ll win this grievance just like we’ve won all the others. I’ll get back to work and a big chunk of back pay too.”

The union filed a grievance on Clyde’s behalf the same day he was fired. At the union hall the next day, Clyde urged direct action by the men. Wildcat strikes, work slowdowns, pickets at the gates. If the company could fire the head of the grievance committee for doing something as petty as selling football sheets and get away with it, what was next? The officers agreed and told Clyde to go home and start preparing his defense.

Clyde expected action right away, but a week later nothing had happened. He started making phone calls to men from all the departments in the plant asking what was going on. They said that the men were ready to hit the bricks, picket, whatever it took to get Clyde back. But the union president and vice president were urging caution. One of Clyde’s buddies told him that he smelled a rat. At a nearby bar a couple of weeks ago, he’d overheard the union vice president tell a guy who didn’t like Clyde that maybe Clyde was too radical to be union president. Maybe the powers that be in the union were not so unhappy that Clyde had been fired. Clyde almost started to cry after he hung up. He hadn’t figured on the union being fucked up too.

As the days passed, Clyde tried to stay optimistic. He met with the union lawyer and planned strategy for the arbitration. When a worker was summarily fired, the first steps of the grievance procedure were skipped, and if the union demanded it, the case went straight to arbitration. They worked out a witness list to show that gambling pools had been routinely administered for more than thirty years, and no one, worker or supervisor, had ever been disciplined for doing so. They developed their main argument, that the reason for Clyde’s firing was not his gambling pool but his union activity, his aggressive grievance filing and success in prosecuting them. Clyde was certain he would win the arbitration. Still, the union’s apparent unwillingness to do more made Clyde’s spirits sink. He might get his job back, but there would be no triumphant return, no arousal of the men that might make the union stronger.

To be continued . . .