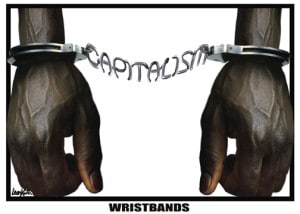

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 had the champions of capitalism crowing that history had ended, that there was no alternative to the “magic of the marketplace.” Historical developments since then have given some credence to this view, as even China has rapidly moved from socialism to capitalism and in the process become a global economic powerhouse. But while the triumph of capitalism over socialism appears to many to have marked the final demise of the radical project, appearances can be deceiving. The disappearance of the Soviet Union weakened the strength of our most powerful ideological construct—anti-communism. Practically every dimension of life in the United States has been organized around fear of and opposition to communism. Any critic of capitalism was charged with being a red or having communist sympathies and could not hope to have much influence. Radicals were purged from the schools, from the government, from the unions, and they were denied access to the media. Communism was the embodiment of evil, and those who were communists or in any way sympathetic to its ideals were evil people, deserving of public scorn, prison, or, if necessary, death.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 had the champions of capitalism crowing that history had ended, that there was no alternative to the “magic of the marketplace.” Historical developments since then have given some credence to this view, as even China has rapidly moved from socialism to capitalism and in the process become a global economic powerhouse. But while the triumph of capitalism over socialism appears to many to have marked the final demise of the radical project, appearances can be deceiving. The disappearance of the Soviet Union weakened the strength of our most powerful ideological construct—anti-communism. Practically every dimension of life in the United States has been organized around fear of and opposition to communism. Any critic of capitalism was charged with being a red or having communist sympathies and could not hope to have much influence. Radicals were purged from the schools, from the government, from the unions, and they were denied access to the media. Communism was the embodiment of evil, and those who were communists or in any way sympathetic to its ideals were evil people, deserving of public scorn, prison, or, if necessary, death.

In terms of my labor education, a turning point occurred with the election of the New Voice slate to AFL-CIO leadership in 1995. The old Cold War apparatus that had supported U.S. imperialism for so long was partially dismantled, and the Federation and some of its member unions became more open to left-liberal and even radical ideas. I noticed that I could discuss the political economy of Karl Marx more openly and that students were not only receptive but enthusiastic. Workers had always had an intuitive grasp of concepts like surplus labor time and surplus value, the inherent and ineradicable conflict between themselves and their employers, the reserve army of labor, and the apologetic nature of mainstream economics. But now I didn’t have to beat around the bush, and I could cover more topics in greater depth. I could ask students to imagine alternative modes of production and distribution and different ways in which work might be organized, and at least some of them would know what I was talking about. They could begin to see that it is capitalism itself that is responsible for their problems.

Anti-communism also served to make workers here xenophobic, blaming those in other countries for the depredations of their own employers. Not that many years ago, many of my students were ignorant of or hostile to workers in the rest of the world. Union workers were unaware of the efforts of their own unions, in collaboration with their employers and their government, to destroy progressive labor movements around the globe. Today, the rapid globalization of capital offers opportunities for radical labor educators to challenge the isolation of U.S. workers. Auto workers cannot ignore what happens in Japan, Mexico, or South Korea. In the past, there was some truth to the notion that workers in this country benefitted from the exploitation of foreign workers, but this is not the case now. Workers everywhere are in competition with workers everywhere else.

I have had some success in promoting the necessity of an international working class response to international capital. When workers become aware of the conditions under which their brothers and sisters in poor countries labor, they are sympathetic. They are interested to hear about efforts to forge international class solidarity, against free trade agreements, for example, and surprised to learn that such efforts have sometimes succeeded. They are impressed to hear that unions in other countries have helped workers here to fight against their employers, and I am sure that they would be willing to help workers elsewhere if given concrete ways to do so. It is not that hard to explain to them that it is their employers and not foreign workers who are the main beneficiaries of capital’s enhanced mobility. They have been told that the only way to meet the challenge of global competition is for them to work harder and for less money. Naturally, they do not like this, given that they have been doing just that for years without benefit. The alternative strategy of doing whatever they can to help poorer workers improve their circumstances, to force capital to stop pitting one group of workers against another is appealing to them.

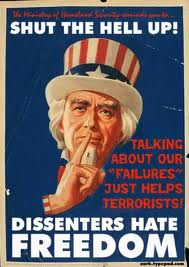

The working people I have taught have always been supportive of Keynesian macroeconomic policies. Now it should be easier to argue for large reductions in defense spending and for increases in social welfare spending. The unwillingness of the government to support policies that benefit workers can now perhaps be confronted directly as a part of the capitalist system in which business exerts dominant control over public policy. This will be especially the case when a Democratic administration proves to be no more capable of promoting fundamental change than a Republican government. Independent politics is in the air right now, and while much of it has been channeled by powerful economic interests and the right-wing media into the reactionary politics of groups such as the Tea Party, it might, under the certain circumstances, develop into something like a labor-based political party. Certainly, labor educators can now openly argue for this. They can pretty much be as radical as they want.

I teach mainly union workers. They have never been more receptive to radical ideas, never more open to the notion that capitalism cannot, ever, be the vehicle of their liberation from the drudgery or work and the insecurity of daily life. Yet, the unions continue to shrink in numbers and political influence. There is plenty of pent-up anger among the working people of the United States, but this hasn’t translated into a growing working class movement. Every day for the past few weeks, we have been watching on television the mass anger of Egypt’s educated but jobless youth and its frustrated workers erupt into vast and well-organized demonstrations that have paralyzed the country’s economy. The corrupt and murderous government, a compliant ally of the United States, has been powerless to stop them. They have forced the odious multi-billionaire Mubarak and his family from power after thirty-two years of dictatorship. This is a country where poverty is beyond the grasp of most of us in the United States and where the risk of confronting the government is infinitely more risky. In Egypt, class power is on display. Time will tell if it spreads and deepens. But if this can happen in Egypt, where no one would have thought it possible just a few weeks ago, it could happen anywhere, even here. This is why it is always important to fan the flames of struggle, in the streets and in the classrooms.

Nice read on the fall of Communism. It opened my mind to the new possibilities.

I have been reading your mini-lectures here, and I have a problem with the overall thrust. I read in a column that a recent Gallup poll revealed the following self-identification of Americans:

42% Conservative

35 % Moderate

20% Liberal

After the upheaval of the 60s, the failed wars and the trillions of dollars in education, this is what our country has come to: 97% in fundamental alliance with nonsense (conservative), vacuousness (moderate), and fraudulence (liberal). How could anything truly reformist happen in that milieu?

Let’s say that leaves 1% identifying as, what, “radical”? And of those folks, how many of them can tie their own shoes?

The Middle East is a far, far cry from the US of A.

I just don’t get the fundamental cry of “radical possibility” – based on what?

Martin:

I think that the thrust of Part 4 is in the title: “Renewal?” with a question mark.

I do not agree with you that the US population is as unaware as you seem to indicate that something is drastically wrong with capitalism. I am less pessimistic. I think that if a poll asked people if there were willing to consider socialism as an alternative to the current system you would find that you would obtain different numbers.

Polls are often misguiding as people in general have only a very vague ideas about the actual choices they are provided with. People in America are alienated and most of them know it and sense it but are not sure why, what is the cause, and they definitely do not know that there is an alternative: Socialism.

The recent events in Wisconsin does show that workers can and will get together to fight back when it is made evident to them that the battle is about class interest. The Wisconsin workers realize, I think, that they are not only waging a battle to maintain their own standards of living but that they are waging a battle for the entire working class. In that I think we can find solace and I think that this is what this blog post is all about.

To prove the point that people in Wisconsin realize that their battle is also a battle for the entire working class, see this video made by a local artist:

http://theviewfromsteeltown.blogspot.com/2011/02/madison-wisconsin-protest-set-to-arcade.html

I agree that Americans are “alienated,” but the events of our times indicate that “the People” is a useful fiction for those at the top. The elite power grab has succeeded in taking so much of the riches and the rights, that a push-back in Wisconsin still leaves the political process in the hands of criminal hacks there, and in Cuomo NY, and all around this country. What do you think we will win in Wisconsin? Even the unions are agreeing to financial give-backs beforehand, and there is no real chance of major labor representation anywhere.

Polls are indeed confusing, but not the basic one I cited. What could be plainer? The American people are conservative, dumb-founded, capable of being roused to shout about their own self-interest at extraordinary times, even while all that cannot be nailed down around them is being or has been stolen.

There are some fine folks out there talking about “fighting” and “new” this and “overcome” that and “socialism,” but the cars on the roads, the empty abandoned buildings, and the super-yachts, and the anti-depressants, and the bored students, and the obese elderly, and the drones and the killings testify to a more dominant social reality.

It’s much harder these days, if not impossible, to suppress information about foreign labor movements, corporate malfeasance, enrichment (indeed obscene enrichment) of management and falling real incomes for workers. Which is not to say that such information has a big impact. Consider Thomas Frank’s book “What’s the Matter with Kansas ?”.

A problem with Keynesian macroeconomics in our current situation may be the near term arrival of peak oil and gas. Kick starting a stalled economy works if the wherewithal for continued economic growth is available and only needs a nudge or two in the right places to get back in gear. Lacking a basic resource (adequate energy), what happens?