A few weeks ago, I was a guest on a radio show hosted by Ed Martin on KDVS in Davis, California. The Egyptian revolt was in full swing. I said:

A few weeks ago, I was a guest on a radio show hosted by Ed Martin on KDVS in Davis, California. The Egyptian revolt was in full swing. I said:

I know there’s a lot of pent-up anger. If you take a country like Egypt, where people are suppressed, when they get an opportunity, a real opportunity, like what happened in the wake of the revolt in Tunisia, they will do things, they will take to the streets, they will show just how angry they are, just as, when the peasants in China got a chance to get back at landlords, they did, in 1949 after the Communists took power. In the United States, you wonder about that sometimes. I’d like to think that would happen, but I’m not at all certain that it would. Those of us who want radical change have our work cut out for us here in this country.

A short time later, I did another interview on the same station, this time with France Kassing. Some of what had happened in Egypt was now taking place in Madison, Wisconsin! Tens of thousands of protestors were marching, and the capitol building itself had been peacefully occupied. The demonstrators were opposing right-wing Governor Scott Walker’s plan to terminate the collective bargaining rights of the state’s non-uniformed public employees.

Over the past four years, millions of people in the United States have lost their jobs, and many of them have little prospect of finding a new one. Millions have lost their homes. Hunger, homelessness, and hopelessness stalk our streets. Profits have been restored, thanks in large part to government bailouts and near zero interest rates, and the financial markets are once again booming. But it is becoming clearer by the day that working men and women face a bleak future, one with limited security, either on the job or from social welfare programs. Every kind of protection is under attack, and if Obama and his deficit reduction commission have their way, we’ll be seeing a major scaling back of social security benefits.

Yet all of this misery had not led to mass protests. There have been some anti- immigration demonstrations and the various Tea Party events, but these were not grassroots movements. Quite the contrary, they were usually organized and funded by corporate interests masquerading as popular outpourings of righteous rage. Then, finally, all the anger and frustration erupted in Madison, in the form of rallies, marches, building takeovers, and runaway legislators, all done peacefully and with humor but also with dogged determination. As I write this, the protests continue. And they have spread to other states as well; support for the Wisconsin public employees around the country is considerable, more than I would have expected given the way public sector workers have been demonized as overpaid and underworked by the media.

As in Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain, and Libya, the confrontation in Madison is not just about specific grievances such as wages or lack of jobs but about fundamental political rights. The issue is democracy, the right of the people to be free of oppression and to direct society themselves. It is one thing to say that the public employees are overpaid (though as studies done by the Economic Policy Institute show, they are paid less than similarly situated private sector workers), It is another to say that they have no right to form unions and bargain collectively. That they should accept whatever their employer demands that they do. That, for example, they be fired without just cause and have no legal recourse. Or that their pensions be eliminated. This finally turned working class anger into action.

Some astute students of the U.S. labor movement have argued that what has been happening in Wisconsin is the harbinger of labor’s rebirth after decades of decline. Given the overtly political nature of this struggle, organized labor may once again be ready to position itself as the fighting force of the entire working class and not just the special interest group that critics say, with some reason, it is now. The immediate question is how to push the struggle begun in Madison forward. Dan LaBotz writes about the possibility of a general strike, something that could build on the private-public worker solidarity evident in all of the rallies so far. Less ambitious job actions could have a similar impact; when workers don’t supply their labor, capital and its allies always take notice. Veteran labor stalwart and writer Clancy Segal argues that the struggle must be taken by workers into their communities, to show that the rights and economic security of teachers and other government employees are the concerns of everyone except employers and the rich.

LaBotz and Segal are correct. However, there are some longstanding matters that must be considered, and these have relevance for radical labor education. The Wisconsin eruption provides radical labor educators with a golden opportunity. Workers are united in the state as they have not been for many years; the general public is supportive; and militant and risky actions have been taken. An “Emergency Labor Meeting,” called in January, was just held in Cleveland to “explore together what we can do to mount a more militant and robust fight-back campaign to defend the interests of working people.” Naturally, Wisconsin took center stage, and the ninety-six unionists present “pledged to make the fight against union-busting and the budget cuts/concessions in Wisconsin the centerpiece of an emergency action plan . . . .” A series of protest days are planned, and the delegates pledged to “link the struggle in defense of labor rights to the struggle against budget cuts and concessions, and that point to solutions to the federal and state budget deficits, including taxing the rich and the corporations, cutting the war budget, and creating 27 million full-time jobs through a massive public works program (which could be launched immediately and without raising the U.S. budget by a penny with a $1 trillion ‘Bridge Loan’ from the Federal Reserve).” Education of rank-and file about the nature of the economic crisis is also high on the agenda.

From a radical labor education viewpoint, what we have is what President Obama called in another context, a “teachable moment.” We should take advantage of this—in our unions, in our communities, in our classrooms, in marches and demonstrations, any place anyone will listen to us. We should, of course, support any and all labor protests and actions in whatever ways we can. But in doing so, we must argue a radical analysis of our political economy. And this requires that we be aware of some basic facts of life.

First, unions have considerable influence in labor education. Many have their own education programs, and they have full control over these. They also are deeply enmeshed in every university-based labor education program, providing some funding, some faculty, and considerable political lobbying support. Many faculty members are closely allied to unions, sometimes serving as consultants. What makes all this problematic is that U.S. unions are notoriously undemocratic, run by lackluster bureaucrats whose main concern is retaining their high-paying positions. Such labor leaders are not going to lead a long-term revolt against neoliberalism. The eruption in Wisconsin has been led by ordinary working men and women and not by top union officials. The latter have been supportive, but they have long and unsavory records of unnecessary compromise and outright disdain for the rank-and-file. What LaBotz and Segal advise will only be possible if union members are energized. This will be unlikely if unions are not run by their members. Unfortunately, this is the last thing union officialdom wants. So sooner or later, there is going to be a lot of internal conflict inside unions as members seeking greater democracy in society run up against autocracy in their own organizations. It will be hard for labor educators to navigate these treacherous waters, but navigate them we must, always pressing the argument for maximum union democracy.

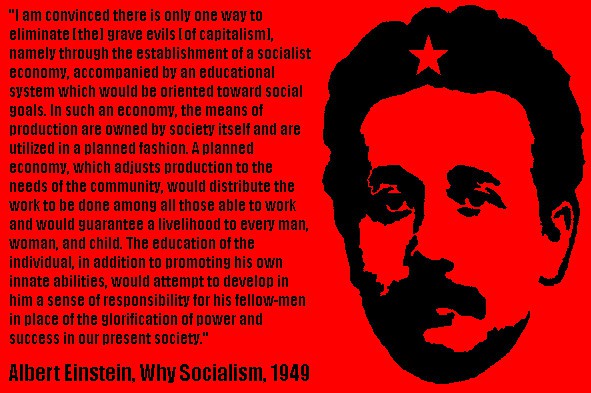

Internal union democracy is a necessary but not sufficient condition for building a labor movement. What is the union democracy for? It must be to help create a democratic society. However, a second fact of life is that capitalism is no longer compatible even with the limited democracy of the United States and Western Europe. The financiers who now dominate global markets want one thing: more money. They will use their enormous power to ensure that they get it. They will move their capital to capital-friendly places, and they will punish any country that caters to the will of its people. There can be no compromise with such people and the system they control. This means that a labor movement and a labor education in alliance with it must be uncompromisingly anti-capitalist. In our classes, in our speeches, in our conversations with workers, we must always stress that it is the capitalist system that it is the problem. Whatever agreements we have to make must be tactical and not strategic. No more labor-management cooperation. No more being the tail of the Democratic Party, supporting the likes of Barack Obama.

If fighting for union democracy will put workers and labor educators on a collision course with union leadership, open anti-capitalism will do the same and more. This will make us enemies of all those who now rule. It will undoubtedly be the case that we will have to devise new forms of both worker organizations and labor education. We have models of both: the IWW of old, the workers’ centers of today, the Party schools discussed in previous parts of this essay. New ones will be built as our struggles continue.

There are other facts of life to confront. The Wisconsin rebels are nearly all white. People of color, including immigrants are the most oppressed members of the working class and the most scapegoated. Hopefully public employees (and all workers) throughout the country will build bridges to these workers, so that a more united working class is formed. Then it will have to be all laborers who are the scapegoats of the right-wing media. War, imperialism, nationalism (in the sense of support for the U.S. government when it acts against the interests of workers and peasants around the world), and the environmental catastrophe in the making will all have to be addressed.

This is a hopeful time. The Arab masses are demanding their full rights as human beings. These are earthshaking events. At least some people here in the heart of the capitalist beast are doing the same. Let us, including labor educators, give our wholehearted support to them and work to build new institutions of struggle and new ways of thinking.