[Note: This story is from my book, In and Out of the Working Class. Counterpunch was kind enough to post it recently.] With a slight shrug of his shoulders, he began to move toward the line. He took four steps, the last one ending in a slide, and as he did so he swung the ball, first forward and then backward in a razor-straight arc until it reached its peak cupped in his large hands about halfway between his waist and his shoulders. On the third step, his arm swung forward, again in that pure arc, and he released the ball just after his swing reached its lowest point. As he imparted just the right lift and spin with his fingers, the ball hit the lane almost silently, as if it had never touched down at all, the bowling equivalent of the dribbling of Earl Monroe, who was able to make it appear as if the basketball never left his hand as he snaked through and around his defenders toward the hoop. The ball slid effortlessly toward its destination sixty feet away, gripped the wood where the oil ended and, now rotating and spinning, drove relentlessly high into the one-three pocket, pushing the pins straight back into the pit. As he stood motionless, his left leg bent and his right hand stretched out and upward toward the second arrow target, Jimmy Beck grinned as he watched his artistry unfold. Around him, the other bowlers, with their nicknames—sky, smoky, moe, pooch, beaver, butch— sewn above the pockets of their team shirts, stopped to watch perfection.

[Note: This story is from my book, In and Out of the Working Class. Counterpunch was kind enough to post it recently.] With a slight shrug of his shoulders, he began to move toward the line. He took four steps, the last one ending in a slide, and as he did so he swung the ball, first forward and then backward in a razor-straight arc until it reached its peak cupped in his large hands about halfway between his waist and his shoulders. On the third step, his arm swung forward, again in that pure arc, and he released the ball just after his swing reached its lowest point. As he imparted just the right lift and spin with his fingers, the ball hit the lane almost silently, as if it had never touched down at all, the bowling equivalent of the dribbling of Earl Monroe, who was able to make it appear as if the basketball never left his hand as he snaked through and around his defenders toward the hoop. The ball slid effortlessly toward its destination sixty feet away, gripped the wood where the oil ended and, now rotating and spinning, drove relentlessly high into the one-three pocket, pushing the pins straight back into the pit. As he stood motionless, his left leg bent and his right hand stretched out and upward toward the second arrow target, Jimmy Beck grinned as he watched his artistry unfold. Around him, the other bowlers, with their nicknames—sky, smoky, moe, pooch, beaver, butch— sewn above the pockets of their team shirts, stopped to watch perfection.

It was right around the time that Jimmy began to tear up the lanes that I hit upon my money-making plan. November of 1958. The year of the big strike.

I was sixteen and a high school senior. I hated school. Teachers kept telling me that I was smart and had a lot of potential. I just didn’t apply myself. If I did, I could go to college and, though it was never said, get out of this one-stoplight factory town. But I was skeptical. I often hear people talk about a teacher who inspired them. None of my teachers inspired me. I thought then that they were a sorry lot. I liked a couple of them. One science teacher was a kindly old man, although his breath stunk. It was said that he had been in the Bataan death march. He certainly looked the part, all thin and gaunt with bad teeth and a pained expression engraved permanently on his face. The social studies teacher, a phlegmatic old woman who moved at such a slow pace that she was nicknamed “Turtle,” tried mightily to interest us in things like the Indian caste system. Sometimes I’d listen, but mostly I would stare out the window at that one stop light as it slowly changed from red to green to yellow, over and over again. All I could do was to hope the bell would ring soon.

When I wasn’t gazing out the window, I filled my notebook with miniature bowling lanes and pool tables. I’d draw a bowling alley, complete with pins and the seven arrows that served as ball targets. Then I would trace out with my pen a perfect strike trajectory, right up high in the one-two pocket since I was a left-handed bowler. Sometimes I’d admit to an error and leave a pin or two. Then I’d draw a new lane and a new line to pick up the spare. Most fun were the splits, a five-ten or a two-seven baby split, or if I were in an adventurous mood, a tough one like the four-seven-ten. After about ten minutes of working out the proper hooks and trajectories, I’d switch to pool. On my tablet table I would lay out a few balls in random spots. Then I would place the cue ball somewhere in the middle of the table and begin to plot out the shots. I’d figure just where to hit the cue ball, how hard, and with what english. I’d draw a line from the cue ball to the object ball, another line from the object ball to the appropriate pocket, and a third line showing how the cue ball would roll after it hit the object ball. This was a great game because I never missed a shot, and the cue ball always ended up in perfect position for the next one.

I suppose that my little classroom amusements would be seen by most people as immature, even pathetic. But in sports and games, the more you visualize what you will do when you are really playing, the more comfortable you will be actually doing it. At home I studied my form in front of the mirror in my bedroom and practiced my delivery endlessly on the linoleum and the hardwood floors. In the cellar I had a set of plastic pins and balls, and I was down there at all hours devising new grips and releases, much to the chagrin of my parents. I also bought books to improve my skills. For bowling I had a book by Buddy Bomar, a professional from Texas against whom my dad had bowled a few games at the naval base in Corpus Christi from which he was being mustered out of the service at the end of the war. Dad told me that German prisoners of war set the pins and the price of a game was three cents. He also bragged that he had beaten Bomar a couple of times, but I wondered about this. For pool my bible was a little gem by Willie Mosconi, who I found out later made the tough shots in the movie The Hustler.

I wanted to do whatever I could to get higher bowling scores and shoot better pool. If you were going to do something, you ought to do it right. You couldn’t use a house ball or a pair of shoes you rented from behind the counter. You had to have your own. This was especially true if you were left-handed. House bowling balls were made for right-handers, so the middle two fingers you use for bowling never fit properly if you were a lefty. The soles of house shoes were either too slippery or too sticky. I bought my own ball and shoes soon after my dad and my grandfather first took me to the lanes. Both of them were good bowlers, especially granddad, who had averaged in the high 190s in the late 1920s, a sensationally high average given the primitive state of bowling technology then. He even had his own radio bowling show, called The Kingpin. For readers unfamiliar with bowling, the kingpin is the five pin, and it stands in the middle of the triangle setup of ten pins. Getting your ball to drive through the pocket and contact the five pin is the key to bowling success. Dad wasn’t as good as his father, but I remember reading in his highschool yearbook that he “could give even his father a run for his money.”

The first ball I owned had a conventional grip, one in which the finger holes were drilled knuckle-deep. The best bowlers were using the fingertip grip, which as the name implies has finger holes only deep enough to accommodate the first finger joints. Such a grip allowed you to get more “lift” on the ball, making it hook more effectively into the pocket and more likely to take out the kingpin and make a strike. I lusted after such a ball. I saved money to buy one, and I got my local alley to get me a discount at the lanes in the next town where they had ball-drilling facilities. My aunt, herself an accomplished kegler, drove me over and I had the new ball drilled— a black Manhattan Rubber. The proprietor said I could bowl a game on the house to test the fit. The ball fit like a glove, and I threw a 242 that first game.

Pool was a little different in terms of equipment. You could get an adequate cue at the pool hall, although the sticks on the racks tended to warp and were often too light. Willie Mosconi said to use a heavy cue, at least twenty ounces, and one with a thick tip. Such cues weren’t always available, so I went to a supply shop in Pittsburgh, about forty miles away, and got my own, two-piece cue, twenty-two ounces, and with a fat tip. My game improved dramatically.

Fantasy and makeshift games are fine, but practice makes perfect. I had to get to the lanes and the pool hall and play as often as possible, especially if I wanted to beat my imaginary scores. But this presented a problem. My parents were strict and wanted to know where I was at all times. And they didn’t want me squandering my money. I had been delivering newspapers since I was twelve, and, compared to the other carriers, I had built a large and lucrative route. I was expected to put nearly all of the money I made in a bank account, to be used to pay for part of my college education, which both of my parents took for granted. The old man had not worked like a dog in the glass factory all these years and my mom had not slaved away at home with four kids to see their oldest child waste his life. Education was the ticket, and there were to be no ifs, ands, or buts about it. This meant that I wasn’t to spend my time in pool halls hanging around with drunks and derelicts. Bowling was okay but in moderation, which meant once a week. Occasionally I was allowed to bowl a game after my father’s and my grandfather’s league games were done, a reward for my keeping score for the teams. But no more than this.

So I waged a war of deception. Some paper customers gave me tips when I collected their bills once a month. I lied about these and kept the difference. I collected pop bottles and kept the deposit money. Sometimes my grandparents gave me money, and this was added to my stash. Once I had accumulated some money, an additional problem arose. I had to find a place to hide it. My father was always spying, trying to find my money. For awhile, I had a perfect hideaway. My father had been a radioman in the navy during the war, stationed in the South Pacific After the war, he bought an old Hallicrafters shortwave radio. He gave it to me, and I had it on the desk beside my bed. I loved how the tubes lit up my room when I turned out the night light. I had a long wire antenna strung out the window and connected to the top of a tall pole to which our basketball bank board was connected, about a hundred feet away. This gave me clear AM reception, and at night I listened to all the great stations east of the Mississippi river, like WOWO in Fort Wayne, WCKY in Cincinnati, WABC in New York City, WBZ in Boston, KYW in Philadelphia, and, the oldest AM station in the country, KDKA in Pittsburgh. I listened to high school, college, and professional basketball games, news from different parts of the country, and rock and roll. The low disembodied voices and the eerie green lights made going to sleep something special. The top of the large radio could be opened easily to get at the tubes, and the ample spaces inside seemed a spy-proof hiding place for my money. It was—for awhile.

Now I had to get out of the house to bowl and shoot pool. It wasn’t hard to get out of the house. But I couldn’t take the bowling ball or the cue stick without my parents knowing my destination. I noticed that neither of them paid any attention to my equipment. I normally kept it in the basement, and, although my mom did the laundry there, she didn’t seem to notice the various boxes, tools, and sundry items scattered about. My father seldom went in the cellar, unless he had to get a plumber’s snake to clean the sump pump. Since they just assumed that the ball and cue were in the cellar, I began to leave them at the bowling alley and pool hall. The counter person at the lanes let me keep the ball behind the desk so I wouldn’t have to rent a locker. Raymie, the guy who ran the pool room, said I could keep my cue in the locked rack at the back of the hall. Now whenever I left the house, I could just hike down the hill to town, sneak off to my two dens of iniquity and practice. I just had to make sure that I practiced at times when none of my dad’s buddies were there too. And I had to get a friend to give me a lift home to put my gear in its accustomed place on those occasions when I might legitimately ask to go bowling or shoot pool. A couple of times when I went to the lanes with my dad he asked me why I didn’t have my ball with me. I told him I had forgotten and left it at the bowling alley the last time we went. He never seemed to catch on. He probably had more important things on his mind.

My father worked in the large glass factory that dominated the town. In fact, the town was named for the founder of the company, a pioneer in the manufacturing of glass. There was a large bronze statue of this man in the town’s park. He had run his company as a feudal manor, much like the small mining towns that dotted the landscape along the wide river which was the source of beautiful white sand used to make the glass. The plant itself was strung out along the river, from the bridge at the lower end of town to 13th street, over a mile in all. The factory was divided into three units: Works 4, Shop 2, and Works 6. Works 4, the largest, was one long assembly line; from Shop 2 came the journeymen who did the factory’s craft work; and at the northern end of the factory, was Works 6, where my father worked. Works 6 was special because the glass was still made in small batches, by skilled workers.

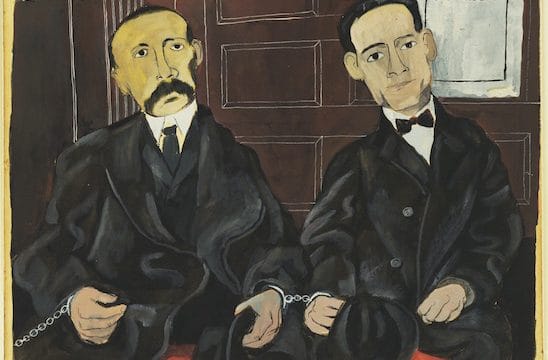

Like many industrial serfs, the men and women in the glass factory joined the great CIO union army of the 1930s and brought an end to their serfdom. The big battles were won after the war when the soldiers came home and took to the picket lines. They had seen too much shit in the war to take much of it at home. By the time I was in the first grade, the factory and the town had been transformed by high wages, good benefits, and a grievance procedure.

But if the union had brought prosperity to the masses, it had also made an implacable enemy of the company. Inside the factory there was chronic guerilla warfare as the workers sought to expand the freedoms they had won with their union and the company tried to win back what it had lost. Grandpa, the bowling ace, was also a time study engineer at the plant. He had managed to master the arcane but potent techniques of Frederick Taylor despite having only an eighth-grade education. During the war, he had even taught time study at a local college. Grandpa was in the front line of the daily factory wars, ever present with his stop watch, trying to uncover ways to make more glass with less labor. Many years later, when my father’s lungs were about to give up the ghost, he blurted out from his oxygen tent in the intensive care unit of the local hospital that his dad had time-studied him once.

Over the long haul, the company waged a war of attrition. Not only would it rely less on union labor by raising efficiency at the plant, but it would begin to open new factories in places where it would be hard for the union to follow. After the war, new plants were built in rural areas far away from the industrial heartland, especially in the South. Once these plants were up and running, they were used to threaten the union plants; either the union would have to moderate its demands or the union plants would close. In the mid-1950s the company discovered a new method for mass-producing plate glass. Rumors began to circulate that the works in our town would be re-fitted for the new process, thus guaranteeing that it would stay put for the indefinite future. But in return the company wanted a rewrite of the collective bargaining agreement, one that would have wiped out most of the work rules the union had fought so hard to secure. When the old agreement expired, the company put forward its radical proposal, complete with a propaganda campaign to frighten the workers and their families. It was common to hear people talking on street corners about the possibility that the factory would close unless the union accepted the company’s proposals. The union and the workers, however, stood firm and refused to make concessions. After ten weeks of desultory negotiations, the union called the company’s bluff and put the workers on the picket lines. For eight months.

At the time, I didn’t know any of this. I knew little about my father’s work, and we never learned about such things in school. My father was an examiner then, one of many jobs he had done over the years. He checked the plates of glass for flaws in front of a high intensity lamp in a dark room, rejecting those pieces with more than a certain number. Other than an occasional complaint about a particular boss or conversations with my mother about his incentive pay, I don’t remember him saying much about his workplace or what went on there. He certainly didn’t tell us about the strike. One day he went to work; the next day he stayed home. Every couple of days, he did his picket duty. I do remember that grandpa stopped coming up to the house. And sad for me, the company-sponsored bowling leagues were suspended.

Most of the factory families lived lives of fixed routines. The husband left home five days a week, not always at the same time since he worked shifts. The wife stayed home and took care of the kids and the household. The kids went to school. Dad brought home the money, and though mom might take care of it, you knew to go to your father if you needed some. His earning of the money through hard work at the factory was what gave him his sense of himself. The strike disrupted this routine and created peculiar tensions. Extra money had been put aside in anticipation of a strike, but no one expected the strike to drag on month after month. The union had a strike fund, but it didn’t come close to making up for missed paychecks. Money was soon in short supply. Mortgage payments, car payments, doctor and dentist bills—all of the mundane outflows of cash that help define a working class life—couldn’t be made. There was no spare change for treats—candy, movies, pizza, bowling; even birthday presents got short shrift. If the women could have gone to work, they would have, but things weren’t set up that way in those days. I began to get an idea of how bad things were when dad “borrowed” the stash of money I had hidden in the radio.

Money troubles were compounded by the constant presence of dad at home. This messed up our daily regimen. Dad did his regular chores, but these didn’t keep him busy enough. There weren’t many of mom’s chores he could do. He could make popcorn, penuche and sea foam fudge, and eggs, but, except for the eggs, these wouldn’t make much of a meal for six people. And if he did the cooking, cleaning, and laundry, what would mom do? You could feel the tensions mounting as they got in each other’s way and as the money supply dwindled. My mother had grown up poor, and the insecurity now enveloping our household was stripping away her normally calm persona.

My parents seldom argued, at least not in front of us. But I woke up one night to hear them talking in their bedroom, which was below my own. My mom was crying, saying, “What are we going to do?” My dad said, “Everything will be OK,” but even the muffled voice I heard didn’t sound too convincing. They must have gotten up and gone into the kitchen, because I could no longer hear them. When I came downstairs in the morning, my mother told me that dad had gone to my uncle’s in Cleveland to help out in his brother’s shop there. He’d make some money, and this would ease our financial woes. My uncle was an artist; he sandblasted designs into pieces of glass. He was talented but a lousy businessman. Mom said that dad would help him with deliveries and collections.

With dad away, mom found it hard to contain her anxieties. She had a perpetual worried look on her face, and when she didn’t think anyone could hear, she sighed. Mom’s anxiety spread to the rest of us. I had a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach, nothing I could explain if asked but a kind of inchoate fear that something bad was about to happen. I tried to lose myself in daydreams. I fantasized about girls, pool, bowling, but my mother’s troubled face kept intruding.

I remember the exact moment I hit upon my plan. I was drifting off to sleep listening to the radio when I heard one of my favorite songs, “To Know Him Is To Love Him” by the Teddy Bears. I was thinking about a pretty girl I had a crush on when it came to me. If I had a stake, I could win enough money shooting pool and bowling to make my mother smile again. The details of my scheme began to emerge as I lay in my bed, and I fell asleep as Tommy Edwards crooned “Please Love Me Forever.”

I seldom went into my parents’ bedroom. Although I never thought of them as having lives independent of mine, some subconscious part of me told me that they did and that it was centered in this room. I entered it with trepidation. My mother was visiting a neighbor, so this was my chance. The room was dark even though it was mid-morning, so I had to turn on the light. I hurried over to the dresser on the opposite side of the room and opened the upper left-hand drawer. This is where my parents kept their envelopes. They had devised a simple scheme to budget their money; they kept an envelope for each spending category. There was an envelope for “house payment,” one for “gas bill,” one for “electric,” one for “groceries,” and so on. Every payday, my father put money in the envelopes, and they used these monies to pay each bill when it came due. After all these weeks of the strike, I guessed that not many envelopes would have money in them. I started rifling through them, and I was beginning to worry that none would contain any cash. But the one marked “house payment” did—$50. I took the money, put it in my pocket, and quickly left the room.

I fussed and fidgeted until my mother came back. As soon as she got in the door, I told her that I had called my friend Sam, and he had invited me to come over to his house. I said that he had also told me that I could stay for supper and then watch television. She said fine but not to be home too late. I asked her if I could come home by midnight, and she said alright. Sam lived a short distance away, so I could just walk. I had another cup of coffee, grabbed some cookies, put on my heavy coat, and left.

I knew that, barring an emergency, my mother would never call Sam’s house, so I wasn’t worried about my lie. When you’re a teenager, lying to your parents becomes second nature, probably a part of your attempt to break free from them and become your own person. I nonchalantly walked down our street toward Sam’s, but when I got out of sight of our house, I turned toward the highway and the path down the steep hill toward town. The path was slippery from the recent snow, and I had to be careful not to slip and have to explain why my clothes were muddy. At one particularly treacherous turn, I chuckled as I remembered how we had pushed one of the snotty little Smolek brothers over the edge the week before on our way to school. His mother had come screaming to our door, but I denied everything and for a change my mother believed me. Probably because she couldn’t stand Mrs. Smolek.

It took me about twenty-five minutes to get to the pool hall. I got my cue from the wall rack and began to practice on the back table. Raymie was cutting hair and selling numbers to a steady stream of customers. Saturday was always a busy day for both activities. Men becoming desperate from the strike gave Raymie their quarters and half dollars and prayed for the number they had dreamt about to hit. I paid no attention to any of this. I methodically practiced my spot shots, banks, and difficult cuts. I knew right away that I had my stroke.

Every Saturday about 1:00 the three Dawson brothers came to town to play pool. “Here come the hicks from the sticks,” we’d say. They were farm boys, big and strong, not too savvy in the ways of the world. Their clothes, their boots, the way they talked, their hand-rolled smokes, everything about them said “hayseed.” Friendly and naive, they were unaware that they were the butt of our jokes. Of course, we were never too obvious, because they were pretty tough fellows.

The three brothers entered the pool room right on schedule. They exchanged a few corny jokes with Raymie and some of the customers who knew them. Just as I had hoped, all of the tables were taken when they arrived. They looked around disappointed and sat down on three of the high chairs spectators used to watch the action when the good players were shooting. After about ten minutes, I walked over and asked them if they wanted to play. They said, “sure.”

The Dawson brothers always had money, and they liked to gamble. After a couple of dull games of rotation, the oldest brother, Roy, asked me if I wanted to play “points.” This was a game of rotation pool in which the five, ten, and fifteen balls were “point” balls, worth whatever amount of money you were playing for. Whichever player pocketed the highest number of balls during the game also got a point. The minimum number of “points” in a game was four. However, it was possible for there to be more than four points in a game. In rotation the rule is that the shooter has to strike the lowest numbered ball on the table with the cue ball. Once the lowest numbered ball is struck, any balls that are pocketed count for the shooter. So, if you hit the one ball into a “point” ball and the “point ball” went into a pocket, the “point ball” counted for you. The same was true if you made a point ball on the break (assuming you hit the one ball first) or by caroming the cue ball off the object ball and into a “point ball.” If a player made a “point ball” out of sequence as a result of a combination, carom, or break shot, this counted as a point, but the point ball was re-spotted to be shot in its proper rotation. It was possible, therefore, that there would be six or seven points a game, or more, so you could win a lot of money in a game. Each player had to pay the others the difference between the value of his points and that of each other player.

To let me know that they weren’t pikers, Roy asked if fifty cents a point would be alright. This was a pretty high stake for me, but I said, “OK.” We played “points” for nearly two hours. The two younger brothers made a few lucky shots, enough to keep them in the game, but eventually Roy and I won their money.

Roy was a goofy-looking character, with out-of-style glasses, greasy slicked-back black hair, and Dickey jeans rolled up at the cuffs. A big-buckled belt, white socks, and worn imitation cordovan dress shoes completed the outfit. He chewed on a cheap DeNobili cigar, which made him look particularly ridiculous, but at least he never lit it. His oddball character carried over to his pool playing. He gripped his cue between his first two fingers, with his thumb up in the air. It was a disarming style, because opponents figured he couldn’t possibly make shots like that. But he could and did. When his brothers dropped out of the game, I could tell he was gaining confidence that he could beat me. He began to chatter and cackle and almost swallowed his cigar when he knocked the cue ball around three rails to pocket a point ball. His brothers cheered and started to make snide remarks about my talent.

I was still a few dollars ahead when two guys I knew asked if they could shoot. Unless two of the better players were shooting for high stakes, it wasn’t acceptable to deny new entrants into a game. Roy thought he was on a roll, so he didn’t care. The new players, “Hack” and “Pep” were good players, and I wasn’t keen on their playing, but I didn’t have a choice. Fortunately, Roy’s luck deserted him while mine went wild. We had upped the ante to a dollar a point, and in the first game, I made an incredible six points to none for my three opponents. I make a point ball on the break, and over the course of the game, I made all three point balls in their turn, made a combination shot which put in a point ball, and pocketed the largest number of balls. Eighteen dollars in one game. An hour later, I walked out of the pool room with about $100 in winnings. Roy and his brothers put on their coats and glumly followed me out. Hack and Pep were complaining that I didn’t give them a chance to get their money back. I ignored them and laughed to myself. My day had begun auspiciously.

Next to the poolroom was a seedy bar, hangout for alcoholics and the boarders who lived upstairs. All day long the bartender and his wife kept hot sausages and sliced onions cooking on a small grill behind the bar. For twenty-five cents you could buy a sausage sandwich served on a hard roll. I bought two, as well as a coke, went over to a booth and gorged myself. Five minutes later, I headed for the bowling alley a few blocks away.

It was just before seven o’clock when I got to the lanes at the Slovak Catholic Union club, “CU” for short. I took my ball from behind the counter, got a lane, put on my shoes, and began to practice. There wasn’t much league action on Saturday night, so most of the lanes were free. I loosened up with a few practice balls, and then I kept score. I bowled two games: 223 and 217. By the end of the second game, I was locked in, every ball driving into the one-two pocket. I was ready.

The good bowlers began to drift in around eight o’clock. A couple of guys practiced, but most of the men stood and talked. There wasn’t much of the sarcastic banter you usually heard and hardly any laughter. Every Saturday night, the town’s best bowlers competed for money. It was called “pot bowling.” Before the strike, games went on long into the night and hundreds of dollars changed hands. The games continued during the strike, but the pots were smaller. And the bowling got more desperate because the men needed the money for rent and food.

Pot bowling was uncomplicated. Each man put money into the pot. Then the men were put into pairs by lot, drawing numbered pills out of a container. One and two were paired, three and four, etc., until each bowler was paired. The pot was split between the bowler who got the highest score and the pair whose combined score was the highest; the high scorer received one-half of the pot and the high pair got one-half to divide between them. The pairs would change every game as would the pair of alleys you bowled on. Usually four to six players bowled on one pair of lanes. How many lanes were used depended on the number of participants in the pot.

I spotted a bowler I knew and asked him if I could bowl. He said that anyone with money could join but I might have to wait if there was not an even number of bowlers.. The men were beginning to put their balls on the ball return, so I took mine and placed it with the others. We began to bowl “shadow balls,” practice shots thrown with no pins set up at the end of the lanes. I counted twelve bowlers, a perfect number—six pairs on two sets of lanes. As if on cue, Jimmy Beck shook the box of pills, and the first set of pairs were formed. I drew a good bowler with the odd nickname of “Shanghai.” I was hoping for Jimmy Beck, but so was everyone else.

As soon as the men noticed that a teenager was bowling, they began to badger me. “Sure you got enough money kid.” “Hope you don’t cry when you lose your dough.” “Hey, isn’t your old man making enough money out there in Cleveland?” This last jibe was made by a big guy nicknamed “Butch,” a person neither I nor my father liked. I was about to say something, but an older man who bowled with my grandfather, and who had recently hit the phenomenal three-game score of 803, said to me in a quiet voice, “Don’t let Butch bother you. The union gave your dad permission to go to Cleveland, and he isn’t getting his strike benefits either.” “Fuck you, Butch,” I said under my breath as I grabbed my ball and took my practice shots.

I bowled very well but not well enough. We were playing for $20 a game. I started with $140, and after five games I was down to $40. If my partners’ scores had been as high as mine, I would have at least shared a couple of pots, but it seemed that no matter who my mates were, they bowled better with another partner. In the second game, I made seven strikes in a row and bowled a 258, but Jimmy Beck struck out in his last frame and made a 259. My partner scored a 180; Jimmy’s bowled a 221.

I thought about quitting. I could put $40 back in the envelope, and maybe my parents would think that was all they had put in it. But I didn’t, and when Jimmy announced that a majority had agreed to raise the pot to $30, I laid down my money. Two bowlers dropped out, and this left ten. There was $300 in the pot, more money than I had ever held in my hand at one time. I promised myself that if I won any money I would quit and go home. A win would mean at least $75; if I got high game and high pair, I’d pocket $225. If I lost, I’d have to go home anyway.

I took my pill and called out my number—eight. I would be paired with whoever drew the seven. Since Jimmy Beck held the pill box, he got the last pill. I listened as the numbers were called out—two, six, ten. I said a prayer, “Let Jimmy be the seven.” One, three, nine, four, and . . . five! Jimmy was the seven. I had a chance.

Jimmy and I were on the right hand set of lanes, along with four other bowlers. The other four players were on the left hand pair of alleys. I liked the right pair better than the left, so I was even more confidant that I would win some money.

For the next few minutes I was in a kind of trance. I visualized in my mind what I was going to do, just like I did in my history class. And then I did it. I was the first bowler, and I bowled first on the left lane of the pair and then on the right, in succession. When the sixth bowler finished on the left lane, I started over again.

Bowlers are always fussing to make their fingers feel comfortable in the ball. Pressure makes hands moist and slippery. Fingers swell and shrink. So they use resin to keep their hands dry, and they keep tape and scissors in their bags so that they can put tape in or remove tape from the holes. Collodion was put on the blisters that often afflicted the inside of a bowler’s thumb. Amazingly, my hands were unusually dry, and my grip was firm and comfortable. I began with a strike, converted a one-pin spare and then threw four successive strikes, each ball setting in the oil and hitting perfectly on target in the one-two pocket. Jimmy matched me strike for strike. We were way ahead of the two other teams on our lanes. I checked the bowlers on the other pair. The score sheets were made of clear plastic and set in a special holder under a bright light which reflected the scores onto a screen above the lanes. I noticed with alarm that “Sky,” the man who had scored the 803, was on a six-bagger—six strikes in a row. His partner had three spares and a triple. They were more than thirty pins ahead of us, and Sky was twenty pins ahead of both me and Jimmy.

I stopped watching our rivals’ scores and concentrated on my own, but I knew that this contest would go down to the last frame. I struck again and so did Jimmy. A collective groan arose at the other table, and I saw that Sky had thrown a difficult split. When he missed, I thought we were home free. But we weren’t, and as I stepped up to bowl my last frame, I knew that this frame would determine the winners. If I struck out, I would have another 258 and the highest score.

I dried my hand over the fan, picked up my ball, carefully fitted my fingers and thumb into the three holes, took my starting position just to the right of center, bent into the stooped stance I had copied from my grandfather and focused my eyes on the second arrow target. I imagined my four steps and slide and then executed them. I felt that it was a good shot right away, and as I watched the ball skid, catch, and hook toward the pocket, I arrogantly turned and walked back to the starting line. I heard the pins crash and peeked around in time to see the last pins tumble into the pit.

I would have bet the money I had saved for college that I would get two more strikes and win at least $150. I repeated the same ritual as I had on the first strike. As I took my second step, I heard Butch say in a voice just loud enough to be heard, “Smart ass fucking punk.” I should have stopped my delivery and started over. But I didn’t and as soon as I released the ball, I knew I had pulled it to the right. It drove straight into the one pin and hit exactly on the nose. Only eight pins fell, leaving the two and four pins. I was so disgusted that I rushed the spare shot and chopped the two pin off the four. My score was 245. I kept my head down as I took a seat.

Sky’s partner finished with a 226. Jimmy decided to wait until Sky bowled before he did, so we all turned to watch Sky complete his game. He had 196 in the eighth frame and a spare in the ninth. He needed all three strikes in the tenth frame to beat me. His first two shots were strikes, square in the pocket. Sky had a crooked face and a hare lip, so it wasn’t easy to read his expressions. But he was grinning as he got ready for his final ball. He threw a wide hook, unusual in that day of hard rubber balls which didn’t naturally curve the way modern balls do. He let the ball go to the right of his usual target, but it came roaring back from the gutter toward the pocket. Then it froze and straightened out just as it hit the pins. This caused the six to fly around the ten and leave the ten pin standing. I rejoiced at the thought of at least a tie for high game, but then the one pin, which had been sent flying to the left, hit the side board at the very end of the lane and came bouncing back onto the lane sliding directly toward the ten pin. The automatic pin-setting machine was in motion, ready to sweep the lane clean and re-rack the pins. “Hurry up,” I shouted, but to no avail. The one pin nicked the ten pin and sent it wobbling into the gutter. Sky had a 246. Sky and his partner now had a team total of 472.

I still had hope. Jimmy Beck had 198 in the eighth frame and a spare in the ninth frame. He could bowl a 248. But he only needed a spare and a small count on his final ball for us to have the high team total. I didn’t see how we could lose. He hadn’t missed a spare all night and had struck almost every time he bowled on the right-hand lane of our pair.

When bowlers throw what looks like a perfect shot and they leave one pin, they say they got “tapped.” The most common tap for a right-handed bowler is the ten pin; the tap occurs when the six pin wraps around the ten pin but doesn’t touch it. There is usually a good reason for this. The ball may have hit the pocket too “light,” that is, not high enough in the one-three pocket. Or it may have hit the pocket at too sharp of an angle. Or a pin may have been “off spot”—not exactly where it should have been as a result of a slight mechanical malfunction by the automatic pin setter. A worse tap, and the only one that bowlers say is a true tap, is the nine pin. Here the ball drives so strongly into the pocket that it hits the kingpin too close to its center, so close that the ball then drives straight through the five and fails to deflect into the nine. Jimmy’s first ball did just this. The crowd gasped in disbelief, and Jimmy shouted out, “shit!” I wasn’t upset though. The nine pin was one of the easiest spares to convert. A righthander just had to stand a little to the left of where he usually began his approach and throw the same ball as for a strike. It was almost impossible to miss. Jimmy confidently grabbed his ball as soon as it rolled up the ball return and almost without hesitation took off down the approach. The ball was thrown off target to the right, but there wasn’t much oil near the gutters, so I waited for it to stop skidding and hook into the pin. But it never caught the lane, and about ten feet from the pin it fell ignominiously into the gutter. His score was 226, and our total was 471. I got my ball and took off my shoes and put them in my bag. Sky said, “Tough luck, kid,” and approached Jimmy to collect the money. I took my bag to the counter and had the counterman put it underneath. I looked back once and walked out the door.

The path leading up the hill toward home was a few blocks from the club. It had begun to rain, so I walked as fast as I could. Parts of the path were icy, and I almost fell just as I reached the top. I once again crossed the highway. I cut through the rear neighbor’s yard and walked around to the front of our house. A light was on in the living room, and I said to myself, “Oh shit. Mom’s still awake.” But she was dozing on the couch. As I opened the door, she jumped up and said, “I thought you were staying at Sam’s ‘til midnight.” I had forgotten about this, but I ad-libbed, “He had a big fight with his mom, so I decided to come home early.” “Oh,” she said. “Guess what?” she asked. “What.” “Your dad called and told me that the strike is over. He said his buddy Nick called and gave him the news. Nick said the company got most of what it wanted, but at least people will be getting paychecks.” I was too stunned to talk, but she didn’t notice and just said, “Boy, that’s good news. I don’t know what we would have done if the strike had lasted much longer.” Then she added, “I baked a cherry pie if you want a piece.” I wasn’t hungry, but I shuffled into the kitchen and ate some pie. Mom said, “You’d better get to bed.” We said goodnight, and I climbed the stairs to my room. I turned on the radio and turned off the light. My bedroom was always cold in the winter, so I piled on the covers, arranging them so the top sheet was the only thing touching my skin. Alan Freed was deejaying on WABC. Conway Twitty began to sing “It’s Only Make Believe.” If only it were. I usually sang along, but I had to try to figure out how solve my fifty dollar problem. The strike might be over, but my troubles were just beginning.