We were in a Wal-Mart in Richfield, Utah. The greeters at the door were an elderly man and woman. Both were in wheelchairs. At a grocery store in Colorado, an old man bagging groceries was so bent over that he could barely look up. In our travels, we have begun to notice a new phenomenon: the working aged.

We all know people who continue to work long past what most of us would consider a normal retirement age. My grandfather retired when he was sixty-five, but he kept working as a tipstaff for a local judge and later, at eighty, took a job keeping the books for an auction company. A recent article in USA Today was full of feel-good stories about octogenarians and even nonagenarians still active at work. Ninety-seven-year-old Al Churchill, who still works every day at the company he founded sixty years ago, says, “If I didn’t work? There’s no such thing. … Work is important, because without work, you’re nothing.”

Mr. Churchill’s sentiments are well and good, but something more is going on here. Saying that “without work, you’re nothing,” means one thing when you are the owner of a company or have a job as, say, a tenured professor at a university, but it means something else when you are an ordinary worker. Churchill owns the company where he goes to work every day. The professor has control over his labor. In addition, the power that Churchill and the teacher have overshadows the inevitable loss of “productiveness” that comes with age. The factory owner won’t be told by his employees that he’s not as in touch with things as he thinks he is. The aging professor can use those old lecture notes and tell the same awful jokes year after year, and then go take a nap in his office. He won’t be fired.

But suppose you are a factory laborer, a secretary, or a hotel room attendant. Your jobs are both physically and mentally debilitating, and you can never do as you please. Thirty years of such work, and you are probably closer to the grave than to a healthy old age of believing that “without work, you’re nothing.” You were nothing when you were working.

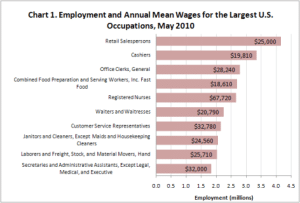

There are many more ordinary workers than there are business owners and professors. Here is a chart from a previous blog post that provides some interesting data. Notice the types of jobs (and the pay) that are most common in the United States. Now imagine saying to yourself at age 65, “Boy, I can’t think of anything I’d rather do than stick with this job for as long as I can.”

None of this would matter much if we were talking about isolated individuals like Mr. Churchill or the waiter I once saw on the Johnny Carson show who was 106 years old. However, some dramatic changes have been occurring over the past decade in the labor market activity of older Americans. Here are the basic facts:

- The labor force participation rate (LFPR, the share of the labor force that is either employed or looking for a job) of those 65 and older had fallen to historic lows by the 1980s and early 1990s, but after that it reversed course and has continued to rise until the present. Between 1995 and 2009, the LFPR for older men rose from 17 percent to 22 percent and for older women from 9 percent to 13 percent.

- The labor force participation rates rose for those between 65 and 69, 70 and 74, and over 75.

- In 2008, half of working men 65 and older were working full-time, up from 38 percent in 1994. For women, the change was from 23 percent in 1994 to one-third in 2008.

- Surveys of those between 45 and 59 years of age indicate that a very high share of both men and women expect to continue working after they reach 65. This share is more than double the fraction of those 65 and older who are now working; therefore, the trend toward rising employment among the elderly will almost certainly continue.

Some commentators have argued that the greater likelihood of the aged to be in the labor force is due to such factors as longer lifespans, better health, higher level of education, and the shift away from hard physical goods-producing labor toward less strenuous service work. These are no doubt reasons why some older individuals continue to seek employment. However, we were living longer and had better health during the decades when labor force participation rates were falling. Higher education is often associated with better jobs, ones that we might want to continue to do as long as possible. Yet, many jobs that require college degrees or more are not easily done by those of advanced years. I taught in a college where the teaching loads were heavy, and I know that I could not be a good teacher with such course burdens now, when I am sixty-six; I couldn’t bear them when I was fifty-five. Certainly, adjunct professors, who now teach most courses in some colleges and have to piece together classes at several schools just to make ends meet, won’t easily be able to keep working into old age. Nearly every Registered Nurse has a college degree, but the work is strenuous and the hours are long. What good will that degree do when the former nurse seeks other employment at age 70? As for service work, look again at the occupations in our chart. Not coal mining, but not very desirable work for the most part. And plenty of service work is physically demanding. Ask a line cook.

The reasons why we are more likely to labor into our sixties and seventies and why so many middle-aged employees are planning to do so are not difficult to ascertain. First, wages have stagnated for nearly forty years, and workers cannot save enough money to guarantee income security throughout their lives. The typical household has retirement savings of just $90,000; at an interest rate of 3 percent, this is $2,700 per year. Second, employers are much less likely to offer and fund defined benefit pensions, in which an employee is guaranteed a certain pension payment each month after retirement. In 1992, 32 percent of workers had such plans; in 2007 this was down to 20 percent. Now, workers either have no pension plan or one with defined contributions, in which workers contribute part of their wages to an individual retirement account (some employers add a full or partial match). How much money is available at retirement depends on how well the financial assets purchased by the account perform. The recession of 2001 and the Great Recession of 2007-2009 wreaked havoc on these accounts, which given low wages, wouldn’t have enough retirement money in them in the best of circumstances. Third, low wages and insecure or no pensions helped to fuel, with the aid of the low interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve, the housing bubble and the explosion of household debt that fueled it. When the bubble burst, the net worth of working people plummeted, making them even less prepared financially for retirement. Fourth, social security retirement ages have been legally increased, and social security income replaces a smaller and smaller fraction of pre-retirement incomes. In 1981, the replacement rate was 52 percent; today it is 40 percent. It is estimated that this will fall to 36 percent by 2025. The long and short of all this is that millions of people will have no choice but to continue working as long as they are able.

Barring a mass political upheaval, the future won’t be very bright for us as we reach our golden years. Every scenario promises work deep into old age. The social security system might be completely privatized, in which case retirement planning will become a completely do-it-yourself enterprise. More than likely, privatization will take place piecemeal, with a series of partial privatization schemes preceding the ultimate demise of the program. If social security does survive, the retirement age will continue to increase and the benefits will get smaller. Benefits might be “means-tested,” that is, there will be an income maximum, beyond which a person will no longer receive or get only partial benefits. Once means-tested, benefits will be stigmatized in much the same way as public assistance. From this, it will be a short step to compelling people to work in order to receive social security payments. A friend of mine referred me to an article in the February 16, 2012 issue of the Guardian (United Kingdom), in which it is reported that: “Some long-term sick and disabled people face being forced to work unpaid for an unlimited amount of time or have their benefits cut under plans being drawn up by the Department for Work and Pensions.” Those ancient Wal-Mart greeters will have to work in those wheelchairs just to get social security. And if they need kidney dialysis, the machines can be hooked up to the chairs while they smile at the customers. Perhaps there will be a nonagenarian so disabled that all he can do is blink his eyes. Then some bright young technological wizard will be tasked to find a way to turn those blinks into labor.

Like lambs to the slaughter, we are being prepared for this bleak future by those who want us to be as economically insecure as possible: rich and powerful employers and their friends in the government they control. They tell us that the social security trust fund is broke (it is not) and can only be fixed if old people make sacrifices. They tell us that the elderly are greedy and want to get theirs while the getting is good and screw the young. When the average social security payout is $14,000 per year, this argument is almost funny. They tell us that since we are living longer, it is only fair that we work longer. They tell us that we have the right to control our own savings (never mentioning that if social security didn’t force us to save, we wouldn’t save at all). They tell us that we would earn a higher return if we invested on our own behalf, never pointing out that the only people who beat the market are U.S. congresspersons and those who are rich to start with.

All of this smoke and mirrors to keep us from thinking that what we need is more security not less, less work not more, time to think, and the resources to do whatever we please. These are the things that will make us “something,” not more years of wage slavery.

In the 1930s, layoffs in a place like Detroit or Chicago would affect workers as a social layer. Since this was at a time when workers tended to live near the factory and even walk to work in many instances and when they hung out at the same saloons or parks, they tended to think in terms of joint action.

But today someone in debt will tend to see themselves as an individual whose adversary is another individual at a bank or a collection agency. Since going into debt often strikes people as a personal failing, they will also tend to blame themselves rather than larger social and economic forces. I was reminded of this the other day when I was speaking to a very old friend about my age who hasn’t worked in a couple of years. Not only is the job market poor, he has developed Parkinson’s, an ailment that will make getting hired as a salesman even harder. It doesn’t matter how good a salesman you are (and my friend was great at this) if your hands are trembling. That is the reality of a fucked-up system that places so much emphasis on appearances.

full: http://louisproyect.wordpress.com/2012/03/19/left-forum-2012/

As all of these forces that you detail so well and succinctly were gathering, where was the US left? Oh, that’s right, meeting and speaking, blogging and writing, lecturing and hectoring, always a change on the horizon, always seeing “encouraging developments,” always clapping for the smallest peep of 60s style “speak truth to power” righteous hornswoggle. Call any of them on it, as I did with the lone commenter above, and watch the spittle fly – how dare you speak the truth about futility?

Where’s the obligatory opto-uplift at the end after all the critique? Are you seeing the same portents of long-term decay and eco-apartheid that other social critics are?

This comment was posted on the Marxmail list, in reference to this blog post:

“At sixty-six I am the fifth oldest employee of a newly opened Chicago supermarket, organized by UFCW. Becoming eligible for Medicare cut my wife, 8 years younger, off our railroad early retirement heath coverage for her. The Cobra payments of nearly $1,000 per month have forced us both back to work. One of my young fellow employees said to me, “I guess you must be bored sitting around the pool all day.” Just as many older people don’t understand the pressures of student debt and low paying jobs for young people, many young people don’t get the diminished circumstances of the gray-haired set. We are all victims of the assault on our class.”

This is right on the mark.

Are you cold forlorn, and hungry. are there lots of things you lack?

If your life’s made up of misery, then dump the bosses off your back.

Are your clothes all torn and tattered?

Are you livin’ in a shack?

Would you have your troubles scattered

then dump the bosses off your back.

Are you almost split asunder,

loaded like a donkey’s back?

Why don’t you buck like thunder

and dump the bosses off your back?

All the agonies you suffer,

you could end with one good Whack!

Stand up brothers and sisters

and dump the bosses off your back.

It’s never too late to join the IWW.

Way to go Mike B) w00t!! Excellent analysis FW Yates!

I presume you enjoy the public debate side of blogging and going on chat shows, like the GNU one, but I think it is a hard role, especially to get much back-and-forth going. Bruce Springsteen, an avid supporter of Barack Obama, was called out by a Canadian critic, who said before he listened to a word of “Wrecking Ball” he needed an apology for the insipid boosterism of the self-anonted voice of the people.

I demand no apology from Bruce, because he is just another industry hack, grabbing his slice of fame through an absurd pose of regular guyism, borrowing faith-head terminology to strut around as some super-corporate savior. He knows his mock-miltiarism will get the rubes to buy his schlock “We Bury Our Own” or some such nonsense, while keeping his tenured faithful in the fold.

But there never seems to be a dissenting word on these forums, or if there is, the hosts spend no time trying to debate – blog honchos as just another paterfamilias boring the family round the table.

The last piece of reaction I have relates to your column before, but brings in antoher piece you have written about. The Us is currently in a 40-year blockade/embargo/ war against Cuba, but I consider the US elite to be in a much longer, much wider embargo/blockade/war against its black and brown and often white poor. Denied the basics of security, as you have explained, the American poor are surrounded by often invisible yet extremely potent forms of economic attack and oppression. Yet within the “heimat,” like the Nazis who used to drive to the Jewish ghettos to jeer and photo and amuse themselves with the available desperate struggles of the doomed victims, well-off, war-enriched Americans delight in rounding up and mocking the desperate struggles of their own encircled citizens.