This past January, twenty-seven year old Ryan Hiller died when a tree fell on his tent cabin during a storm at Yosemite National Park. Tent cabins are structures with concrete flooring and walls, canvas roofs, beds, a dresser, but no cooking or toilet facilities. They are meant for overnight visitors who don’t want to pitch tents or stay in an expensive Yosemite lodge. Ryan wasn’t camping, however. He was a seasonal employee of the Delaware North Corporation, which manages the concessions at Yosemite. Tent cabins were the company housing the corporation provided, and for which Ryan had to pay rent.

This past January, twenty-seven year old Ryan Hiller died when a tree fell on his tent cabin during a storm at Yosemite National Park. Tent cabins are structures with concrete flooring and walls, canvas roofs, beds, a dresser, but no cooking or toilet facilities. They are meant for overnight visitors who don’t want to pitch tents or stay in an expensive Yosemite lodge. Ryan wasn’t camping, however. He was a seasonal employee of the Delaware North Corporation, which manages the concessions at Yosemite. Tent cabins were the company housing the corporation provided, and for which Ryan had to pay rent.

Millions of people visit our national parks every year. They stay in hotels, cabins, and campgrounds, eat in the restaurants, and go on various excursions. You might be one of these persons. Did you ever wonder about the workers who checked you into your room, served your meals, or drove your tour bus? How much did they get paid? What were their working conditions? Where did these men and women live?

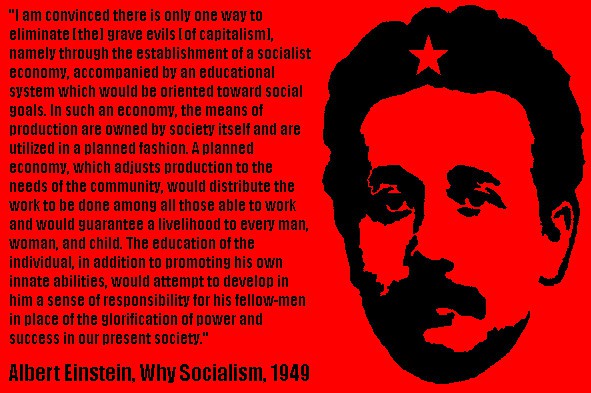

The federal government contracts national park concessions to private corporations. Three prominent concessionaires are Xanterra, owned by billionaire Philip Anschutz; the Delaware North Corporation; and Aramark, the global food and services provider. Park concessionaires collectively now have gross annual revenues of more than one billion dollars!

These businesses build their profits on the backs of some 25,000 workers, most of them hired seasonally. They promote themselves as stewards of the parks, providing ideal jobs for college students, senior citizens, and people who might enjoy living in a beautiful environment. The reality is something different. Many employees are, in effect, migrant workers, who move from park to park during the year and who depend economically upon these jobs. There is nothing ideal about this employment. Hours fluctuate wildly. At the beginning of a season, there are usually too many workers and hours are insufficient; as the season wears on, people leave and hours are over-long. The work is extremely stressful. Tourists crowd the national parks on vacations, and they can be rude and demanding of the staff. A guest at Yellowstone actually threatened to kill a server when he thought she had not treated him properly. Supervisors often run roughshod over their underlings, demeaning them in front of coworkers and guests and making unreasonable demands such as that you can’t get a drink of water during your shift. Unlike most jobs, workers are in isolated areas and often have no transportation, so if they don’t like the conditions and quit (or are fired, as often happens), they must leave the park immediately, losing not just their jobs but their homes and food supply.

One particularly egregious employer practice is the aggressive recruitment of young people from foreign countries, sometimes under the false premise that they will learn national park management and earn enough money to travel in the United States. Instead, these guest workers find themselves cleaning hotel rooms or laboring in hot kitchens, with little time available to see the parks in which they work and no money for travel.

Park concession employees earn extraordinarily low wages, and these become still lower after various deductions are made. Both domestic and foreign workers must pay all their travel expenses. For those who depend on incomes from park jobs, these costs mount because they must vacate housing at the end of the season, find some place to stay for a month or two, and then return to serve the next season of tourists. For example, a cook might work at the Bryce National Park Lodge from April to November, be unemployed for a month or two, and then go to the Furnace Creek Inn in Death Valley National Park. Employees also must pay partial room and board, as well as a health insurance premium. If you get stuck with limited hours during a pay period, it is possible that your wages will be negative after deductions.

Undesirable eating and living arrangements compound low wages and poor working conditions. Poor quality and unhealthful food characterize the fare in the employee dining rooms. Guests receive much better food than workers; they get full-strength orange juice and fresh eggs, while employees get watered-down juice and liquid eggs. We worked during the spring and summer of 2001 at Yellowstone National Park for Xanterra (formerly Amfac). We were appalled when we ate our first meal and discovered that the servers slopped our food onto compartmented plastic trays, just like in prisons.

Living accommodations are deplorable. We lived in a ten by ten room in Teal Hall, an ancient wooden building that looked like a long storage shed. We were fortunate to arrive for our job training earlier than most of our fellow workers, so we were able to scavenge the unoccupied rooms for the best of the ratty furniture and room amenities in them. The tiny hot water heater in our room was good for one shower. We had meager laundry facilities, but at least they were free; in other parks, workers must pay to wash and dry their clothing.

But bad as Teal Hall was, and still is, it is not the worst employee housing we have seen. Hovels, shacks, tents (in Alaska), there doesn’t seem to be a lower limit to the quality of employee housing. Usually, unrelated adults must share spaces too small for either privacy or neatness. These quarters are what workers go back to after a long hard day of labor at less than minimum wage (once travel, room, and board costs are taken into account). Imagine working as a hotel desk clerk—the job I had—standing on your feet for eight hours, dealing all day long with frazzled and irate tourists, missing a meal, and then walking home to your tent. If it is payday, you might delay your misery by detouring after work to the employee pub. At Yellowstone, we were encouraged to give our wages back to Xanterra at the pub, which was one of the company’s most lucrative profit centers.

Recently, the National Park Service approved a plan to allow Xanterra to take some employee housing at the Old Faithful area of Yellowstone and convert it into cabins for guests. This housing will undergo major renovations to be suitable for the tourists:

* The interior of the cabin units will be rehabilitated: new floor coverings, wall coverings, electrical systems, bathroom fixtures, and gas heaters.

* A number of the cabins would be made accessible.

* Pathways to the cabin area will be made safer and more accessible. Many of the asphalt walkways within the cabin area are old and deteriorating with numerous rough spots, uneven surfaces, raveling edges, and missing pavement. These walkways would be replaced or repaired as part of this project.

Xanterra wasn’t concerned with these cabins when the workers lived in them. Who cares if they had safe and accessible pathways and livable interiors? They were only means of production and not paying customers. The corporation is going to build a dormitory for employees, but away from where the tourists stay. Small rooms for two or three people and cheap construction would be my guess.

Stephen T. Mather, the first Director of the National Park Service (1917-1930), said, “Scenery is a hollow enjoyment to the tourist who sets out in the morning after an indigestible breakfast and a fitful night’s sleep on an impossible bed.” These words provided the rationalization for the growing commercialization of the national parks he oversaw. Those who came to the parks then were relatively well-off, and the lodges and concessions were developed with them in mind. Poorly paid workers served them, from the black porters on the trains that delivered tourists to Glacier National Park to the Harvey Girls at the Grand Canyon.

Today, the average tourists are not among the economic elite, but they must have incomes high enough to shell out the considerable sums of money necessary for transportation, lodging, food, and concessions (the off-season rate for a standard king bed room at Yosemite’s Ahwanhee Hotel is a whopping $532.87). What has changed little since Mather’s day is that low-wage labor still does the work, usually after sleeping on “an impossible bed” and eating an “indigestible breakfast.” Rich corporations, poor workers. Sound familiar?

I work for the NPS at Mesa Verde NP, and from what I have seen and heard, you are absolutely spot on about the conditions of concessionaire workers, in this case Aramark. Its absolutely despicable that the NPS, the Federal govt. doesn’t enforce better wages and conditions for these workers. After all, all construction contractors that do work on park lands have to pay Davis-Bacon wages, so why not some standards for service workers?

Sheldon,

Thanks for the comment. I hope many people read my post, and that something gets done about this.

Michael

I’m employee with these companies and especially gm John Kenny at one these parks and God bless America-flashlight cop

I am a retired American who wanted to fulfill their bucket list by working for xanterra at YNP. Everything you wrote is absolutely true. I would hope the national media would pickup on this story. It needs to be told so that when guest arrive at their selected NP they know the conditions the workers are under and their money is supporting the profit of these companies. The NPS needs to wake up and not give these companies contracts unless they improve the pay and benefits of their workers.

Thanks for the comment, LG. You are absolutely correct.

These companies won’t do the work if they can’t make money. If you want the employees to make more money, you might start by convincing the NPS to take less than 15% for doing absolutely nothing.

So you think Phillip Anschutz, one of the richest men in the world, is losing money on Xanterra? Get real.

WOW…I think my mind is now changed. This is America…that is terrible treatment, maybe because the majority are foreigners, young and want the excitement.

Terrible how the corporations get away with this low dog treatment and for workers to agree too the bully treatment given….stand up people !!! Unite !!!!

I worked at YNP and am not surprised by this article. The worst part about my housing was hearing huge bolders falling. It was so loud, it sounded like thunder. We’d all run out of our tent cabins, look up at the rock wall and wait for impending death. Bolders fell on guest cabins and those shut down. They never cared if the employees were hurt. Also, the extreme drug use among the employees was pretty bad. We worked six days a week. When we finally got a day off it was used for doing laundry, getting groceries, etc. I never had the energy to go hiking.

Thanks for this Michelle. This is a sad story, but I think it well reflects the reality of working for the National Park concessionaires.

Come on… If you want to hike badly enough, you’ll just go do it no matter what. There are people who would literally kill to be in your situation and you make excuses.

And if people are not happy about low wages, simply don’t take the job. You can get service sector experience anywhere these days. However, I do agree that workers should be treated with respect and not like numbers.

You yourself have OBVIOUSLY have not worked at a NP, which is why you are clueless in giving such a reply. I am in a technical, mid-management position and FULLY agree with what she said.

Hey, I think I know you! It is sad, I had no idea just how bad it was, even through our phone conversations. I hate unions, but I think you guys have a good case to start one!

Dave

In our modern economy people don’t have as much freedom to choose their jobs. Many have to take whatever there is available.

Well now… “If you don’t like the PAY”… I’m doing this to better myself, and I have family that will help me out if things do go awry…

That BEING SAID>>> SHAME ON YOU BOI !!! You forget the biggest problem of our country… the POOR ARE POOR… Work long hours and try to survive, option one…

Don’t sign up and starve, option two…

There is no choice here BOI so wake up and realize your coffee is made by slave labor, your eggs got fried up by your impoverished neighbor, and your world is a lie…

One more thing, BOI, get yar preettttty bum back where it belongs, and let your ignorance be your bliss… I don’t need it.

I worked in Yellowstone and it was the best summer of my life and changed my course in life. You have to have a positive attitude and stay away from the negative people who want to bitch about everything. I do agree that housing and wages need attention. No doubt. But when writing an article like this, you should also talk about the positive things that come from working in a national park. You are surrounded by beauty and peace. You can hike, camp, raft, go for bike rides, learn about wildlife and tons of other things. Be positive!

In my book, Cheap Motels and a Hotplate: An Economist’s Travelogue, there is a chapter about working at Yellowstone. It includes both positive and negative aspects of our stay there. But in this blog essay, I focused on what needs national attention, namely the use of private concessionaires and their treatment of workers, which is disgraceful.

My husband and I worked at YNP 5 years ago. I was on the room cleaning crew at the Snow Lodge. Yes, it was hard work for a 65 year old lady but there were many young people working with me that pitched in and helped me! We met some of the finest girls from Taiwan and took them touring with us on our days off. We only worked 4 days a week and the park coordinated our schedules. We had movie nights at our dorm and shared many “fun” times with other retired people! I read the complaints and they may be true but I must say, we had a fantastic time while at YNP! The beautiful young people that took us in as “Grandparents” made up for the small room. Their hearts were “big”! You that complain need to see the beauty the parks have to offer!

Thank you for a positive attitude. We have spent a great amount of time in 2018 and 2019 as camping visitors in Yellostone, and we talked to so so so many employees. Everyone said they loved it, tho most were RVers. No one complained about the cost of room and board. They said it was cheap compared to real life outside the park. When we’d ask, “C’mon, what’s it REALLY like?” they said exactly what you said – “Best ever back yard, stay out of the fray, and you’ll love it!.” You know, just like you have to do in ANY job or living situation, even if it’s with family who love you. Thanks Terri, for a real world perspective.

Cindy, How is yours a real world perspective? You camped. Big deal. We actually worked there. Read my book Cheap Motels and a Hot Plate, not to mention the original post. Do you think I am lying? Do some real research. Better yet, get a job at one of the hotels. You spoke to RVers! Older people often living in expensive RVs. They don’t do much of the shit work in the parks. Maybe reach out to people in other parks, living in tents and other decrepit housing. Like one of our sons, who has worked in three national parks.

When workers are killed in National Parks due to employer negligence, and these concessions are not held accountable, and still operate in a “business as usual” way, in spite of multiple OSHA safety violations, you see that decrepit housing and inhumane conditions eventually lead to an uptick in worker deaths. Don’t go looking at the Bureau of Labor Statistics CFOI for the truth, because they utilize “data suppression” to hide them. I know. I am now living with this nightmare since my young son was killed while at work at a National Park.

I am so sorry for your loss. It is impossible to imagine your loss. I hope that everyone reads what you wrote and think about what it means. It is employer neglect that is responsible here, as is true for most workplace fatalities.

I’ve worked at 8 different national parks in the past 21 years. They’re all different and all concessionaires are different. I’ve seen some horrible things go on. The park service keeps everything quiet along with the companies. No one knows or understands until they work at a park. Some don’t pay overtime until 48 hrs. One I applied at was 56 hrs. Visitors think it’s a paradise. I just tell them I don’t have time to look around,I work for a living.

Thanks for this comment. Amazing after all this time, people still find what I wrote and make a comment.

This Metate worker agrees!

I work for Aramark they dont look after there staff its all about the money, its all about the bottom line,plus its tax exempt at Yosemite

I agree, John. Why others don’t see this is beyond me.

You got it exactly right!!!! i have worked for all of these concessionaires… Xanterra, Delaware North and Forever Resorts and Vail Resorts All of they provide the same unimagineable awful food, housing and work you to death for around $9.00/hr. I always wondered why the NPS doesn’t make things better for employees and the J-1s have it bad… I feel so sorry for them… They have a company rep visit their country and glamorize it! when they get to the US (it costs minimum $1000 for airfare they pay themselves) it is so different than promised…. i will never work in National Park again!!! If tourists only knew what the employee had to deal with… if they only knew… Xanterra is the worst company but not by much.. all operate and give the employee low wage, small share room with a psycho you don’t know, out of control drinking…. it is a down right shame.

Thanks for this, Sue! Curious that poor people no doubt can’t afford to visit the parks. So, the employees are slaving away so those with means can enjoy them and often enough treat workers badly.

I worked at yellowstone park as a dishwasher then busser then server in 1998. I knew what I was getting into. I think they paid me about $2.17 an hour as a server even though our tips averaged about 5% as many of our international guests were not aware of the custom.

Only way to spend a summer in yellowstone that I knew of–good luck getting a job with the national parks. If you have a pulse these guys will hire you.

Company sponsored outings, could ride the tour bus all day and learn all about the history of the park. Found my crew with the same days off, had a sweet manager that worked really hard so we could have the same days off every week and stick with our crew. Still had plenty energy left for hiking.

Oh did I forget–free passes to Yellowstone and Tetons, come and go as you please.

Talks hosted by winterkeeper–amazing.

Best summer of my life. I stumbled on this site because I was thinking about a fella I met there that I didn’t keep in touch with. What made me think of him? I don’t know, I guess I’m getting old.

I knew I was getting hosed by a company making billions off the backs of us. And I was young and didn’t realize how much it would end up costing me to keep my student loans in forebearance for so long.

In hindsight even though I don’t come from money or anything, I enjoyed a socioeconomic privilege I didn’t even know that I had, in order to have the choice to make that kind of trade off.

They do come into your community colleges, which was where I signed up, and make a nice glossy presentation. I then drove 20 hours alone across the country, did lots of stuff that scared me, basically became an adult, met people from all over the world, changed my life forever.

Needless to say I would do it all over again in a heartbeat.

Thanks for your comments. I enjoyed being in the Park too. But aren’t there larger issues at stake? Xanterra is owned by one of the world’s richest men. He’s not a particularly nice guy. I am certain he voted for Trump, who would, if he could privatize the parks and open them all for mining and other nefarious activities. Why should workers be so underpaid? Why should living conditions be so horrible? Etc.

I spent 4 summers as a fishing guide in YNP from 1965-68. I wouldn’t trade that time for anything. I shared a cabin with 1 other guide. The food was not gourmet for sure but was pretty good. Wages were low but tips were usually quite good. You shouldn’t take a job like that if you expect to make a lot of money. It just won’t happen. Go there for the experience , get away from home, learn responsibility and meet people from all over the world. This was over 50 years ago and I still maintain contact with co workers all over the country. Beats the hell out of flipping burgers for next to nothing at your local McDonalds !

Thanks for your comment. However, you were there 51 years ago. Don’t you imagine that things have changed dramatically since then? We made good friends too and had many good times. But that is not the point of the original essay I wrote.

Well, everybody, the reviews are available for all to see. No one is forced to work at the National Parks anywhere. These locations are a gamble, you must do your homework and investigate all Concessionaires. None of them offer any Employment that is long term because they operate seasonally. When applying with these companies it is Russian Roulette, it really is your choice to go there after all. Marketing a company and advertising a beautiful location is what these companies are good at. If you choose to go there you really need to be prepared for all situations.

J1s, J2s and H2Bs have access to the Laws in the USA but are too lazy to inquire. I have worked at numerous National Parks throughout the country and NPS doesn’t need to care. It really is up to Future Staff to delve into the History of these places as far as Employment.

I have met very few who understand the laws and fewer still who act when they need to.

So my advice is look elsewhere for Employment for this kind of living/working is for a different breed of human.

I work for Xanterra at the Grand Canyon, and you are spot on in your assessment. Living conditions are deplorable, working conditions arent much better, most of the management is even worse. If I didnt have such a love for the park, backpacking, and the outdoors I wouldnt be here. Spread the word brother.

Skywalker,thanks for your comment. I have been posting my article on the various national parks facebook pages. Hopefully, this will increase the number of readers.

I worked for Xanterra in 2007-2008 and back in ’98 when it was Amfac – Both times at the Grand Canyon. Although the first time sucked (housing screwed up and my roomate was my damn manager), the 2nd time was not bad at all. Yeah, Colter Hall is old. It was built in the 30’s but that is part of the charm. I worked at both Hermit’s Rest and Desert View – yeah, hours were long. 10 hours a day/6 days a week and pay wasn’t great but who cares. Millions of people a year spend thousands of dollars to visit the park for a day or two. I had a whole year to explore. And my paychecks were about 500-700 dollars biweekly after they took out the $30 for housing. You want to talk abut slave labor? Take a good hard look at the Walt Disney College Program. They pay LESS then minimum wage since its an “internship” but in reality it is slave labor. We get free admission to the parks, they get thousands of college students for $7.05/hr. Housing – I paid $80/a week to share a 3 bed, 2 bath apartment with SIX outher females. There are no EDR’s or discount food options. You need to provide all food yourself at overpriced grocery stores. One of the housing complex’s is called VISTA WAY but it’s is more famously nown as VISTA LAY. It could make girls gone wild look tame!

Laura, you review is making me laugh. Glad that the second time around you were more acclimatized, which only seems natural.

I was wondering what kind of safety briefing you folks were given as far as free time in the park? Are there signs posted along rives, streams, and lakes warning of dangerous waters? Were you told not to “float” the streams and or lakes? Did have a safety class conducted by Park Rangers?

If you have anymore stories or photos, please share. You can post them on the FB Yellowstone National Park Employee Alumni page, too.

take care,

zako

Yep, I was GTNP and Yellowstone 2004-2007. Grand Teton Lodge Company one year: miserable. Flagg Ranch Resort: not half as bad. They’re privately run and treat employees with slightly more respect but it is still pretty terrible (hours etc).

A Wray,I posted this on several facebook national park sites. No one yet has had anything good to say about these employers. wonder why?

What an excellent post! I traveled to six national parks in the Four Corners area in May and found conditions that are described accurately in this blog post. Foreign migrant workers, low wages, no benefits, poor living conditions, and supervisorial intimidation of workers. The service to visitors is also declining and prices are going much higher.

This is no less than government mandated and enforced guaranteed profit — where’s the competition? It’s a shame to stay in the parks…just outside the gates are better accommodations and meals are much lower prices, offering greater amenities. We found that except at Mesa Verde, which are so remote, there are no motels right outside the gate! Otherwise, stay away. Better yet, write to your congress critter and the National Park Service and complain about the over commercialization of our parks.

Joan, Thanks for your excellent comment. Yes, we should all demand of our public officials that they do something about this. Michael Yates

Here we see greed at work because amidst the high profit that these entrepreneurs or owners are earning, they can’t even give a decent lodging and food for those working for them and who contributes to creating that profit for the company.

Who owns our National Parks?

This was the question the came to my mind, after staying at Yellowstone and Grand Tetons just last week. Everywhere, we saw Xanterra employees. They were very reticent to talk about the organization and didn’t want to talk about who owned it and ran it. When we visited Yellowstone in 1988, many of the jobs now done by Xanterra were done by NPS employees….which means, lots of the profit from the Parks today goes to a billionaire, not put back into employee benefits, park maintenance, etc. Philip Anschutz is commonly identified as the “Christian Republican philanthropist.” He gives money to global climate change deniers and “intelligent design” promoters. See the Wikipedia article about him. He is a heavy contributor to conservative political and religious organizations. I plan on contacting my Senators to make them aware of this and try to get some kind of investigation going.

Paul, Thanks for the informative note. I will check out that wikipedia entry. The national parks continue to deteriorate, in more ways than one. If Anschutz has his way, commercialism will reign still more supreme. Let us know what your senators say. Michael Yates

Michael.

Would you please email me? My teenage child is working in a national park and I have some serious concerns not addressed in you article. I need help/direction.

Thank you

Hi Paul, you hit on a something most people fail to realize. I applaud your efforts and hope to hear if you get any type of reply. That billionaire that runs Yellowstone National Park, he does not even have a clear idea of what goes on there. When he visits things are clean up. When the owner or a government representative visits, rooms are specially prepped for such visits. That are not put in a room with a leaky roof or mold growing on the window seals. I walked passed the laundry room at Mammoth hotel several days per week while I was there, each time I would cringed.

I currently work at Mammoth hotel as a housekeeper and you are right. When management hears of NPS inspections everything gets cleaned up and all the maintenance problems get fixed but quickly fall into disrepair after they have left.The housing is awful and the food is worse. The international staff are all college students some paid $5000 to come and work here just to scrub toilets 6 days a week and is it’s not 6 days of work it’s 2 and a half where you make almost no money after they take out the cost of poor living conditions and over priced low quality food. However the international staff is as interesting as living in Yellow Stone. Beautiful place lots of new interesting ideas form all over the world. That’s why I’m still here but I don’t think I’ll do a second season under these conditions.

Paul – Respectively it has not been my experience that jobs the NPS used to do are now done by Xanterra employees. You may find a few minor things but not many if that. I started 51years ago and and worked the past 4 summers and have my own perspective. Maybe not your experience. Xanterra does manage the campgrounds that you can make reservations for.

As a current employee at the Grand Canyon, I can say the issues have little to do with Mr. Anschutz and more to do with a long standing corporate mentality that takes for granted the contract within each park is locked up secure.

Personally, my view is that very few companies would tolerate the micromanagement that NPS has over the concessionaire. NPS likes Xanterra because they can bully Xanterra. I can’t imagine a Marriott, Sheraton or the likes tolerating NPS telling them exactly what they are allowed to have on the menus, the exact decor of every building,down to what types and colors of paints are tolerated, etc. Xanterra is easy to bully.

Seriously, why should NPS care if a restaurant serves toast or what color the paint is in a guest room? Guest and employee safety should be their concern, but they waste time on things like I just listed and basically ignore safety. And Xanterra is fully aware that NPS does not focus on this, and does not take time to care for it themselves. Black mold in employee housing, broken appliances and furniture, rodents, and overgrown weeds-things that would never survive code in a major city are common. NPS overlooks these issues.

Do I think NPS needs more funding? Perhaps.But what funding there is needs to be redirected toward safety issues and not to the micromangement of the concession. Our government is not in business to run hotels- leave that to private businessmen! Perhaps if it were left to private businessmen to run the hotels, and they did not feel bullied by NPS, the parks could operated by concessionaires who took care of their employees and guests alike, instead of a corporation that is rated asone of the worst in this country to work for.

I doubt Mr. Anschutz’s personal politics have anything to do with the deplorable conditions in the parks. Much of it is the fault of NPS whose focus is entirely misdirected.

As a Christian conservative myself, I would like to see a little more of the golden rule and respect for a Creator God that we will one day answer to for the way we have treated others and stewarded that which God has blessed us with- i.e., the park’s natural beauty- be a relevant part of the park’s management. I think it is exactly that disrespect that causes our problems in the first place.

Yes, Xanterra is a poor choice of concessioanires. But until we encourage a better comcessionaire to come within the park bounds by allowingc them to run a business as they known it shold be run, things will only change for the worse.

Rodents at Jenny Lake Lodge in GTNP are protected. They have a “catch and release” policy, rather than “trap and dispose” like everywhere else I’ve been. I was quite amazed at the number of mice running around EVERYWHERE towards the end of the season there. I’m all for respecting nature and wildlife, but damn… Amazing they don’t get Hantavirus problems.

Overgrown weeds? Personally, I think natural plant growth is one of the best things about national parks! I loved the “overgrown” grass and so called weeds at Lake Yellowstone and throughout Grand Teton National Park. Very pretty! Wild strawberries and raspberries were absolutely delicious compared to domesticated farm berries. Last year at Mammoth Hot Springs, I found wild choke cherries and crab apples just outside the park, which was a lot of fun, even if they didn’t taste as good as domesticated varieties.

Mammoth Hot Springs does things more like a mini-city — noisy sprinklers often woke me up at 3AM or 4AM, and then if that didn’t do it, noisy lawn mowing would wake me up at 6AM or 7AM. I despise lawns in the city — people waste a lot of water on them, waste time mowing them, and often they pollute the air using gas powered mowers with no emission controls. It’s a shame that Mammoth has such manicured lawns.

Code compliance constantly snooping around my house and coercing me to destroy harmless plants in the city is one of the things I absolutely LOATH about city life.

Yes, I realize there are some typos in my posting. Please excuse them and look at the message itself.

Redheaded Ranter, Thanks for your note. You make many good points. I have no love for the NPS either. Rangers work collecting money at the gates, when they could be doing bettr things. New trails are not built, horses run amok on trails, and a spirit of commercialism reigns. We have disagreements about the concessionaires, although we agree on some things. One matter you don’t mention is wages. I don’t think the NPS sets these, and there is no reason why the concessionaire can’t raise these. And they could improve at least the interiors of worker hou sing, cut weeds, etc. All in all, the whole park system is deteriorating, and no one seems to care much. Again, though, thanks for your message. And don’t worry about typos. I make plenty myself!

I’m considering working at GC for Xan this season. Not doing it for the money… Are there alternatives for housing – I’m in my 30’s, no desire to do a dorm environment, plus I have considerable food allergies… Thoughts? I have a car – I’d be happier sleeping in my tent than a roomie or finding alternative housing.

Annabelle- curious what you found out about housing? I am considering GNP this summer, also in my 30’s. Does anyone know the current pay rate for seasonal workers with Xan? For 2014?

I’m going to work in Yellowstone for the summer as a server and I’ll be making $4/hr plus tips. Housing/food is 200/bi-weekly. I figure, if I hate it I can always just leave.

This is the most logical statement I have read..Nobody forced anyone into these positions..If you don’t like it, go elsewhere. That is called Freedom.

Another libertarian chimes in. Yes, the rich and poor have the same “freedom” to sleep under the bridge. A pretty limited view of freedom.

So how was your experience? My 18 year old daughter will be working at Grant Village this summer as a hostess and now I am having some serious concerns!

Ellen, My original essay is critical of the big transnational corporations that hold the contracts for the parks’ services. They leave a lot to be desired as employers, and I think that the federal government should investigate this and do something about it. Just because these are seasonal workers, they should not be exploited. However, this doesn’t mean that a young person cannot have a good experience. If you read my book, Cheap Motels and a Hot Plate, in the chapter on Yellowstone, where I worked, you will see that we had an overall good experience. It was like life, there were good and bad aspects. But I am an economist, and an expert on work, so I tried in the book and in this blog essay, to bring my knowledge to bear on working in the parks, in my case, for what is now Xanterra.

I am considering a job offer to work at Desert View in GC year round. I just would like a clear view what I might expect as far as housing and pay rate. Anyone have an idea. Would this really be worth the move?

Desert View year-round is a sweet, albeit somewhat remote gig, with relatively decent housing.

Hi Everyone!

Great post and comments.

I received an offer from Xanterra to wait tables on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The offer says $5 + tips + $16/wk for dormitory housing. I have two questions:

Does anyone know how much a server makes including tips per week?

And, how bad is the dorm housing? I met a couple employees one summer who were living in the cabinets outside Maswik Lodge. They didn’t seem so bad…

If you have an RV, many parks have RV sites set aside for employee use.

a coment from a recent german visitor of yellowstone

in the motherland of capitalism this kind of monopoly position of e.g. xanterra – at least interesting – some competition might improve conditions for workers and guests.

See on the xanterra webpage the information that workers who fulfill there contract get a 3$ per day extra at the end – how bad must the conditions be to implement such kind of thing – But why should the pay more than absolutely necessary as long as enough people will do this jobs – Profit maximizing seems to be a true feature of the capitalisic system. And in other areas (e.g. textile workers in developing countries) we also don´t care about conditions as long as we save money.

It is actually a common custom to offer an end of year bonus by even the better companies. It is nothing unusual.

EAST German visitor I’m sure. Sounds like conditions in the parks are similar to what they were in the East Bloc til the 75 Years War ended in 1989. I think I prefer Capitalism to the Stasi lording over the Wonderful Socialist Paradise of the GDR.

Sky, what are you talking about? How would you know where this visitor came from? His comments seem right on the mark to me, and all you can do is red-bait him.

He probably knows from the commentator actually stating he is from Germany.

This concessionaire presence in national parks is not only bad for workers–but bad for travelers. My family stayed in the signature tent cabins of Yosemite in late August — run by Delaware North Company — where the recent hantavirus outbreak occurred. I am trying to make sense of the relationship between the NPS and the concessionaires and in the midst of my research I came across a comparative analysis of NPS, state park and international parks as they relate to several facets of contractual terms of concessionaires. One thing that I found very interesting and disturbing (and is related to lodging for both workers and travelers) is that the NPS concessionaire contracts require the concessionaires to set aside a maintenance fund for repairs of buildings, etc. The state parks and the international parks also require concessionaires to set money aside for maintaining facilities. However, the NPS RETURNS the balance of the fund to the concessionaire at the end of the year giving the concessionaire NO incentive to make the necessary improvements!

Thanks, Janet. The more I learn about the parks, the worse I feel!

I am speaking from the standpoint of a local who is lived in Yellowstone (or surronding community) my whole life . I’m willing to shed a little light on the subject.

1) This year the concession contract is up for bid i.e. who is willing to contribute the most to the maintenance fund which is used by the NPS for special maintenance projects – roads, buildings, trails, and cell towers (the #1 visitor complaint is lack of cellphone service).

2)The rangers at the gate are not real rangers, they’re “interpretive” rangers meaning their only job is to talk to visitors. Agreed, slighty ridiculous, but that is their job description.

3)You’re all right. The lack of competition fosters the poor living conditions and deplorable pay. What’s also kind of discouraging is Xanterra hires a high percentage of those with criminal pasts because they’re sometimes the only ones desperate enough for the pay.(cause it makes sense to hire sex offenders to live in co-ed dorms right?)

4)As a concessionaire worker, most are there for the scenery and the experience – not the income. Which is sad, because many tourists leave Yellowstone with a bad taste in their mouth due to crappy customer service and astronomical prices.

Thanks, Catheryn,

It’s a sad state of affairs that private contractors run the parks at all, and that true rangers are used for what they should be trained to do. Money rules the day in every aspect of our public lands, including the parks. Thanks for your comments.

Michael Yates

Let me correct a couple of things Catheryn has said here. First off, the NPS does not use money paid by concession operators to pay for cell tower expenses. Those towers belong to the carriers and the carriers are responsible for them. Neither NPS nor any of the concession operators have anything to do with them.

Second, all NPS personnel who wear the green and gray uniform are rangers. There’s no such thing as a “real” ranger vs. one who is not. There are different categories of rangers, however. There are the law enforcement rangers, who are federal police officers. There are interpretive rangers, who are the ones who staff the visitor centers, give guided talks/walks, etc. And so forth. The gate operators are known as Visitor Use Assistants (VUAs), and they work for the Chief Ranger (the head of the law enforcement division), and they are just as much rangers as is every other green and gray wearing person working in the park. Don’t denigrate their service because they don’t carry guns. And the interps do far more than just “talk to the visitors.” I’m surprised someone who claims to have lived in the area for so long isn’t aware of these basic facts.

Having said all of this, the general bent of the article is right on the money. Xanterra is really bad about hiring people who shouldn’t be there – they have to hire over 3,000 people each summer, though, and that’s the size of many small cities in the country, With that many people, some are going to be criminals.

Xanterra also goes out of its way to fire people for the least little thing. I’ve seen them fire someone who’s worked for them full time for 20 years for a simple administrative error, yet near the end of the season when staffing gets tight, they allowed someone found possessing a HUGE quantity of drugs to stay on the job.

There’s an old rumor that goes around every year about the site Personnel Managers getting their bonuses based on the number of people they fire. I haven’t been able to prove that isn’t true (I’ve worked for Xanterra). The housing sucks in many instances, too, as was pointed out in the article, and the EDR food…just, damn, it gets really disgusting by mid-season. There is a reason why Xanterra is consistently rated as one of the worst companies in America to work for.

As for internationals, Xanterra hires a bunch of them, but they have a good reason to do so. The American kids they hire get to the point where they just want to get drunk, lay around and not work. They don’t have that problem with the Internationals. Those kids come in, put a full day’s effort in, don’t drink, don’t steal shit, and don’t cause much trouble at all (occasional exceptions, of course). But the point about those kids ending up in the hole when they leave is right on, too. Very, very few of those kids return because they always end up shafted at the end of the season. Xanterra has two people from Yellowstone alone who travel to other countries to try to get the Internationals to work in the park.

Anyway, Catheryn’s misstatements notwithstanding, the vast majority of the article itself is right on the money.

Yeah, I wouldn’t be surprised if they get some sort of bonus for firing people at will. It seems to depend on the site though. Lake Yellowstone fired people right and left. Mammoth, not so much. Grand Teton Lodge Company scarcely fired that I could recall.

I hear ya on the American kids getting drunk. And smoking pot. And not showing up to work on time.

Internationals are often better behaved. But they still occasionally do the same crap as the Americans. It is quite a crime that so many of the Internationals have little hope of recouping their expenses. From talking with them, the plane tickets are expensive, and worse yet, they have to pay “Organization” fees to some middleman that does all the paperwork to get their Visa and jobs lined up, which is usually why these Internationals can’t make a profit working here.

Certain countries have lower “organization” fees, and those kids thankfully can make a profit by coming here. I had a good friend from the Ukraine one year at Jackson Lake Lodge, GTNP who said he definitely made more profit by coming to the USA to work for the summer than trying to work in his home country. Macedonians seem to be profiting and return multiple years. Moldovians, no such luck, organization fees way too high. Polish, no profit unless they can work their butt off by taking up a second job outside of the park.

Some of the concessionaires charge their employees less than others for room and board. GTLC had impossibly cheap room & board, which made it easier for the Internationals to profit, although my experience was that the food was not as good as at Xanterra/YNP. Xanterra charges quite a lot (comparatively) for their employee’s room & board, plus they tack on mandatory MEDCOR medical clinic fees (even if you never use the clinic). At Mammoth Hot Springs, I had to pay Park County income taxes out of every paycheck, which was unexpected considering Wyoming has no income taxes and besides, I thought the entire park was Federal land, not county land.

I witnessed the majority of the foreign employees slacking in their duties this entire summer. From going to lunch clocking back in and then disappearing back into the EDR to socialize with their other friends that are now on their lunchtime. Also becoming so drunk knowing that they were to work the next day in one situation a girl should have gone to the hospital yet another staff assisted this person in getting back to their dorm from the bar, and then a Nother person ended up checking in on this girl all night after she was just left there to rest. I would often find a couple of the Taiwanese employees who would be out late at night would come to work with us during the day however they would go into a closet and sleep while on the clock .

Often, most particularly with Asian employees, would not be working in the area that they were assigned. They were assigned area going to area at their friends or a girl or boy they were interested in or working so that they can socialize.

In my experience over the last summer there were only three American employees that did not work hard task that is fair to overgeneralize a group in the work habits .

This is all so damn true!!!, I worked for Xanterra’s location in Death Valley, for 2 years in which time i spend doing deplorable work, lived in shitty employee housing with black mold and Asbestos popcorn ceilings, often shared rooms with many undesirables, including, drunks, drug addicts,and undesirable foreign workers, etc.

the food is fucking horrible! you are forced to eat in a cramped employee dining dungeon, given less than 30 min to force down the MSG/ frozen warmed up food you are rationed, often the cooks take so long to serve you once you finally get your food you get about 12 min to eat it.

At the location I worked at I was once at in death valley, one night i was watching tv in my employee dorm room to suddenly be startled by high pitch screams, the screams were coming from down the hall about 3 doors down, i quickly threw on some clothes because i thought a woman was being beaten to death, i pushed open the door to this room where the girl was screaming thinking i had to pull some drunk guy off his girlfriend, although what i saw was far from the truth it wasn’t a fight at all but a suicide!, the girls boyfriend has hung himself by the neck from the shower head in the bathroom with an electrical cord…

I will never forget the sight of the dead man and the state of horror, and shock i was in at that moment in time…

Xanterra of course swept this incident under the carpet as usual, in fact i was forced to attend work the very next day after witnessing this atrocity, i was even the one that rushed to the phone to report the incident, i have been really fucking emotionally disturbed ever since.

Although later i found out that the suicide I witnessed was not a solitary event, in fact a year before it happened another employee before I worked there committed suicide by shooting himself in the face with a shotgun…

Thankfully due to family circumstances i left Xanterra thank god…

PLEASE! ANYONE SEEKING EMPLOYMENT FOR XANTERRA DO NOT BE FOOLED OR SUCKERED INTO THIS SLAVERY SCAM.

SAVE YOURSELF I AM SPEAKING FROM PERSONAL EXPERIENCE, YOU WILL REGRET WORKING FOR THESE NAZI’S…….

Thanks, Andrew. This is a shocking story. Yes, those who run the concessions in our parks are among the worst and most despicable employers. Your advice at the end is sound, to put it mildly. I hope that you are OK. Please take care of yourself. Michael Yates

Wow. Andrew I was right across the hall from you in that dorm that fateful night. I should say I have seen that girl from time to time in the parks and she is doing well, although she does not work in the parks any more.

I stumbled upon this blog post while filling out applications. I won’t repeat any thing in the blog post since it is very accurate. I will add Americans are not lazy drunkards as some have implied. The internationals can get just as crazy and are also poor performers on the job. I am a 10 year victim of the concession life and my time working in the parks at least with Xanterra will end soon. As in my case the concession companies don’t try to keep reliable employees like myself who’s only goal is to improve guest’s vacations in any way possible. Although I will say conditions have improved slightly and I have managed to get 401k and health, it is because I have struggled to stay with the company and have overlooked all their underhanded dealings. There will never be a professional class of employee in the parks. The guy that owns Xanterra has very little to do with how the parks are run, it is all dictated by NPS and it is they who needs to fix this problem. Xanterra has invested about 135 million into YNP( and get the contract for 15 more years) and now the penny pinching begins. My job has been combined with others and they now lose a mature professional employee. As I tell people my tolerance for the mistreatment is a testament to my love for the parks.

Robert, thanks for these comments. I doubt that Xanterra’s owner, Philip Anschutz, a multi-billionaire, cares about the parks. Only money and power.

I have to say, I spent several seasons working for Xanterra at GCSR, and in general, it was great. Xanterra is certainly no worse than any other company I’ve ever worked for–sure, they care little about the well-being of their employees, but like I said, no less so than any other company I’ve come across.

Ultimately, the only reasons I left Xanterra were a) my position left no room for advancement (because the people in the positions above me had grown up in the park and essentially had tenure/were never going to leave…but this was a position that was above minimum wage, and had the status for decent housing, which I worked my way up to. The specific politics of my department were my hindrance to advancement, not Xanterra itself). And b) I was in my mid-20’s and felt like, socially, I was wasting my best years. I absolutely loved my community there–made up of Xanterra, NPS, GCA, Delaware North, and Tusayan folks–but I was surrounded by folks in their late 30’s and up. I rather enjoyed the simplicity of life there, but I knew that I’d wake up in 10 years and wish I’d spent my 20’s being a 20-something, not going to bed at 8pm several nights a week.

I understand that my experience is limited to specifically what I’ve experienced. I know that Xanterra life isn’t always pleasant–the time I spent in the dorms wasn’t my favorite–but it wasn’t any worse than it would have been elsewhere. Guess what, working retail or waiting tables or cleaning hotel rooms in the “real world” would have landed me in equally as bad or worse living conditions as at Xanterra (and yes, I can say that with absolute certainty, because I still work in one of those fields, in management, and the current housing I can afford is worse than Xanterra’s). The kinds of positions that Xanterra employs don’t earn a living wage ANYWHERE. That doesn’t make it right, not at all, but it doesn’t make Xanterra any worse than anyone else.

MamaBird,

Fair enough, though yours is a distinct minority of the responses so far. You are wrong though about workers elsewhere in the economy. Lots them make living wages doing work people at Xanterra do. Room attendants in Las Vegas, for example, with a strong union,do make a living wage and good benefits. Lots of cooks do too. Others as well.

Michael Yates

I stumbled across this on a google search about Yellowstone concessionaires. I was researching for a friend who’s thinking about applying for a dining room serving position this coming summer. I have worked seasonally in the park for DNC for 3 seasons now. After reading reviews, I am glad that I don’t work for Xanterra. DNC had decent EDR food, we generally didn’t work more than 40 hours/week, and people were not randomly fired. But there were still issues.

But as for working for DNC, they are all about making money. Guestpath is just a front for the company to pursue money-making avenues, which include low wages, high rent/food/medical costs for seasonal employees. Don’t get me started on their Greenpath program. It’s kind of ironic that DNC has Greenpath when most items used in their soda fountains are disposable. I would love to see a statistic on how many tons of waste are produced each year.

It seems like every year I go back, working conditions deteriorate a little more. For example, this past summer we had a enough drama to film a reality series there. The shortened version is that we had some internationals try to game the US immigration law by getting ‘married’ to other seasonal workers so they could remain in the US. It was a nightmare. They had no respect for anyone else, and management should have fired them. But they didn’t because they didn’t want to get involved in a liability issue. These people finally quit, but then everyone worked 6 days/week until the end of the season (this was mid-August).

It’s a shame because I love living in the parks as I am a major hiker. But I would love to see these companies care a little more about their seasonal employees because the tourists do notice how tired and disheartened employees are. But I doubt anything will be done about it.

Dear J, Does DNC run what used to be called the Hamilton Stores? Sounds like conditions are none too good, which is what most of the comments here say about park work in general.as well. It is tooo bad, and not right either. Why should those who work in our parks be treated badly? Maybe I will start writing to people in Congress about this. BTW, there have been some insane soap opera type things in Yellowstone with Xanterra. A friend of ours worked there after we left, and for several years she kept us posted about work at Yellowstone. Some crazy stuff! Thanks for posting about your eperiences.

Did you work at Old Faithful this story sounds exactly like what happened last year.

Dear Michael,

Yes, DNC runs what used to be Hamilton Stores. I believe they took over around 2003/2004 because a lot of my friends from the 2005 season, missed the Hamilton years.

DNC took over in 2003 that was my first year,still work there no problems with this company for me.

We worked for Hamilton Stores Inc. a family operated corp. Couldn’t have asked for better….they were good to their help.

This article brings up some good points. But also overlooks some stuff. I worked for Xanterra at Grand Canyon South Rim for a summer, and then for Ceder Fair in Ohio and I will be headed out to Yellowstone this summer.

Housing at Grand Canyon was not that bad, but it does depended on who you choose to hang around. Considering how little you pay to stay so close to some of the most amazing places anywhere, its pretty ok. You are in a remote area so there might be critters, if you are not ok with that I am not sure why you would be going out to yellowstone or grand canyon in the first place. They can put up hotels and shops, but it is rugged wilderness if you step off the trail!

Are you a “wage slave” maybe, but for many of the people working there, even just seasonally, would they really be better off working minimum wage for a similar company in the inner city? It is a risk to go out there… But if you don’t get involved in crazy drunken parties or do drugs and show to up to work and do your best your probably won’t get fired. I knew a few people who got fired from Grand Canyon, and I know why they got fired. If I was in management I would have fired them too.

I defiantly agree with the thing about foreign workers… but then again I think the company’s need to go recruit foreign workers says more negative things about american work ethics then the companies policies. However with that said it would be nice if they recruited more here in the states, at college campuses and so on.

In the end I think it is a lifestyle choice. You will run into people who feel stuck and hate it. But you run into that everywhere. Most people know the risks when they go out. I know I do, I’ve read some pretty crappy stuff on the internet but for me I would rather take the chance to go somewhere amazing that I can’t afford to vacation to, make a bit of a paycheck (in a state with a higher minimum wage than my own) even if it means crappy housing and crappy work. Cedar Fair definatly stank, but who else would have hired me for 3 months? If I stayed home I would probably have a crappy job anyway.

Ria J.L. Thanks for sharing your experiences. Maybe what we should be thinking is why any job pays a very low wage or has bad conditions, no matter where it is. And maybe we need to ask why our government would grant concessions to private companies, which are then allowed to do basically what they please in terms of employment conditions. Why shouldn’t our government set the tone for good working conditions, which might then put pressure on all employers to follow suit. I get upset with the argument that, well, jobs are even worse someplace else, so this one isn’t so bad. We should all have greater expectations!

I had the pleasure of working for Aranark in Denali National Park for the last 2 summers. While the ultimate reason I left was the lack of benefits and full time employment, I do have to way, McKinley Chalet Resort sure did things right for there employees. For $15 a day, employees got housing (which as of this fall were going through an upgrade process before guest rooms), 3 meals a day in the dining room, which always had a vegetarian option, as well as a better salad/ sandwich bar than the buffet restaurant, access to free laundry, fitness and activity center, and 50% off food at the restaurants and 25% off retail. I was a manager of the front desk, and my employees had shared housing with one other person, and shared a bathroom with one other room. Front Desk employees were also given the chance to do all excursions free at the beginning of the season, like helicoptor and airplane tours, atv’s, 4×4’s, golf, bus tours, etc. The wages were on the lower end, but all employees were given a end of contract bonus if they stayed until the end, wnich was .50 centa for every hour worked. Front desk alei received bi-weekly commision based on excursion sales. Are you going to get rich working at one of these places, not likely, but these were two of the best summer’s of my life, and I an a little sad that I am back in the real world.

Ok yet another disgruntled employee perhaps? Sorry after 15 years, I’m not seeing a lot of what you say to be true. Yes the wages should be higher but, the living conditions no. The tent cabins in Yosemite are pretty bad but that’s one place. ever worked at grand canyon north rim staying in the “new dorm”. Its just like a nice hotel room with your own bathroom, walk in closet, and plenty of space. From my experience the only people who write up columns like this were usually the trouble makers that worked in the park and could not get away with having there cake and eat it to. And the statement about safety, uhhhhh ok back up. From the way you make it sound what, did you sleep through all the safety drilling they constantly harangue employee’s about?

Wow, what a response to your article. Didn’t have time to read through all of them but one thing that needs to be brought up is what happens to these employees during the off season. The only option is unemployment compensation as it is impossible to save enough during the tourist season being paid such a low wage to make it through the winter. Here in Utah, home to 5 National Parks, the employment season is generally 7 months long in a good year. That leaves a balance of 5 months for employees to survive on an allowance of $200 (less 15% taxes, thank you President Reagan)with a limit of $2600, or 13 weeks. Try paying your mortgage, car payment and feeding your kids on $170 a week. And whatever you do, don’t get sick. And did I mention that the Sate of Utah has no overtime compensation law?

Doug, Thank you for this. The response has been amazing. But what to do about it? Letters to Congress? You are right about surviving in the off season and health care. Also, what about employees having to pay their own transportation out of the park when the season ends, and then back to their jobs when the season begins again? Surely the companies could pay for it, certainly for those workers who have a long work history of working, leaving, and coming back for a new season, or those who move from park to park and work more or less year-round.

I must say, while there are some good points made in this article, the generalizations are way to strong and I disagree with with the broad brush the author uses to paint the situation. I worked at Yellowstone for two seasons, and many of the “exploited” foreign workers I shared space and jobs with were back for second or third seasons. I lived at both Lake and Old Faithful, and while the living quarters at Old Faithful were old, they were comparable to many college dorm rooms across the country. When I worked for Aramark in Alaska, I found the living quarters to be a little more spartan, but again comparable to a college dorm room. As for the complaint that the jobs don’t provide year round housing and employment, that’s correct, they don’t. The very nature of the jobs is that they are seasonal.

To Doug: Utah doesn’t necessarily need an overtime compensation law. Overtime is regulated by the Fair Labor Standards Act (a federal law, meaning it applies to all U.S. states). This law guarantees overtime pay for anyone working non-management, non-professional, etc. hourly wage positions making less than $455 per week. If the law has been violated it is up to the victim of that law to report the issue to the Utah Labor Commission.

For those that believe rangers that collect entrance fees should be doing better things for the parks than collecting money: The Federal Land Recreation Enhancement Act provides for the collection of fees in federal lands. Someone has to do the collecting, unfortunately/fortunately it is left to a federal employee. In NPS’s case, it is left to a visitor use assistant (ranger) to collect those fees. It is law, and the law has to be carried out by someone.

As for all NPS employees being rangers, this is subjective and debatable. Yes, all NPS employees have the option of wearing uniforms, some positions are mandated to wear uniforms. I would pose the question though, is an I.T. systems administrator at a park a ranger? How about budget technician? Maybe a park vehicle mechanic is a ranger? What about a contract representative? Meh, to each their own. I’d like to think they are all rangers at heart, but it is still debatable.

As for bullying concessionaires like Xanterra; I worked for NPS for several years in one of the top ten most visited parks in a budget management capacity (as well as several ranger positions). I never saw bullying of concessionaires, and I never “bullied” them either. Concessionaires are under a time-limited contract with NPS to provide services. Xanterra and others happen to put in the most amicable/beneficial bid each time contracts are publicly announced for bid requests. The concessionaires that have filled back to back contracts continue to get awarded these contracts in part because they state they are able to provide services for the lowest cost. The government likes low cost. One way the concessionaire is able to do this is by providing what could be considered an unacceptable work condition by many former concessionaire employees.

Is NPS micromanaging concessionaires? I do not believe so, especially from my experience with the Park Service. They are too busy micromanaging other things, concessions micromanagement is low on the list. They do however benefit from money generated from concessionaires. The concessionaires provide funding for special projects inside the park that are taken on by NPS.

As for requiring the concessionaire to set aside funding for maintenance of the buildings they conduct operations in; that requirement is individual to each contract. Not all contracts require money to be set aside for maintenance. Occasionally, concessionaires operate out of historic structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These are maintained by trained cultural resources staff (archaeologists, preservationists, anthropologists, etc.) and skilled maintenance staff rather than concessionaire employees. Sometimes the concessionaire is responsible for the maintenance of the building. If the living conditions of a structure inside the park are deplorable, and the concessionaire won’t do anything about it, please please please inform NPS management of the park. There are many funding sources available to fix these kinds of problems. No one should have to live in a deplorable building, especially when the visitor rooms around them are often near luxury status.

As for the comments regarding working for less than minimum wage after housing, food, and insurance are deducted from paychecks; I’m sorry that’s a very spun way of looking at things. Dang, I work for less than minimum wage too after “I” deduct rent, student loan payments, car payments, insurance, utilities, and food too. Just because you chose to live in concessionaire provided housing, accept their meal plan, etc. and “they” deduct it from your wages before you receive your check doesn’t mean you work for less than minimum wage. Although I say this, it doesn’t mean that you don’t work for abysmally low, unfair wages. Please note that no one forced anyone to work for the concessionaires in parks. Baiting foreign individuals, students, and others with rainbows, learning experiences, sunsets, incomprehensible compensation packages, and promises of hopes and desires that can’t be guaranteed, or controlled by the concessionaire, is unfair, wrong, deceitful, and should be stopped immediately when it happens.

Living in the resort areas around parks is expensive, and employees should receive wages that allow them to have decent living conditions. Unfortunately NPS has no control over this, and it is solely up to the concessionaire to determine wages. The obligation that the concessionaire has with NPS is to provide services to the visitors of the park. How they choose to do that is ‘generally’ up to the concessionaire as long as they follow applicable state and federal laws. The concessionaire only runs into serious trouble with NPS if they fail to deliver their end of the contract (providing visitor services). This is difficult to change, the best way of changing the situation is by voting with your feet (many seem to do this by quitting in droves throughout the season), and then writing the park management, regional NPS management, your representative, and the contract officer that approved the contract or put out the bid request for services. These bids are public information, and often those involved in the process have their names attached to the bid request. If the contract officers are aware of unreasonable situations that occur with concessionaires, they will have a justifiable reason to deny the contract to an underperforming concessionaire when the contract is up for bid again.

As for the living quarters in Yosemite that are basically cement boxes with a canvas roof and other similar housing units; If those housing units couldn’t pass a building inspection in a nearby city or town, they should not be allowed to be used as “housing” for concessionaire employees. Putting people in sub-par ‘housing’ is wrong, and then charging them for it is ridiculous.

Crazy things happen in any business and area where the labor force is seasonal, large, and unstable. This is hard to fix in a tourist related park where things are so dependent upon weather, school schedules, etc. If tourism was consistent, stable employment, long-term employees, and a less haphazard environment would exist. A good comparison would be cruise ships and the community of seasonal, transitory, and temporary employees that live/work on them.

Yes things need to get better in regards to concessionaires and the contracts they operate under as well as the way they operate. It is a huge issue that will cost a ton of money to the tax payer, a huge time investment by NPS, and more public attention needs to be brought to the issue. However, it needs to be done constructively, and that is the most difficult thing of all. Everyone wants to rant and rave, but it is very difficult to get all parties to sit down amicably to invest the time and resources into improving the situation.

Just 2 cents from someone who spent several years working in several positions in a big park.

I must say that if it wasn’t for me working for Xanterra in Yellowstone, I would be up sh*t creek quite literally. The program here, yes it’s a lot of hard work, but compared to other seasonal jobs it’s actually pretty nice. Before you go bashing these seasonal jobs, why don’t you take a look at the DIRTY industry of Amusement Parks—where because of being under the dept. of agriculture in most cases, the employees earn LESS than minimum wage, barely make enough money to support themselves.

Here in Yellowstone, we are provided dorms which come out of our pay check, as well as 3 meals a day (may not be the best, but its food). Whereas places outside of the park are now giving less than 30 hours a week because they don’t wish to be paying the healthcare insurance for their employees, housing rates for an apartment are more than a person earns, and sometimes people are having to pick up 2 or more jobs just to support themselves….

I am happily returning to the park, yes the hours are long, sometimes the work not so glamorous, but I’m getting at least 40 hours a week, with food and housing for less than an apartment outside the park would cost. As I said maybe before you bash these type of jobs, you should look at Amusement parks where the employees could easily work 80+ hour weeks, WITHOUT being provided overtime due to how the parks are classified, and having to choose cheap food to live off of due to not making much money….

Ellen, Thanks for your comments. I am glad that things worked out for you. However, I thinkk that sometimes we have too great a tendency to look down, so to speak, at situations worse than our own and say, well, it could be worse. I was born in a shack in a coal mining town, with no hot water or indoor plumbing. Was this better than living in the woods. Yes. However, the owners of the mine, who got lots of money only because they owned the mine, lived a lot better. They certainly didn’t work harder than the miners. Xanterra is owned by one man, who is one of the richest in the world. Huge profits flow to him whether he works or not. We could take the view that we should do what we can to make sure that all working people get a good wage and benefits. He certainly could afford it as far as NP workers are concerned.

I am relieved to read some of the balanced comments by: Ron Doering, Ria J L,R, Ellen, Chris Millet, BCN , as I am headed for Grand Canyon South Rim by July 3 to work for Xanterra in Guest Services.

From my job offer, I know what my wages will be. I expect to share a dorm room in Colter Hall. I don’t know what it looks like, but I will bring bleach in case I see mold. I will pick up groceries if I don’t like the employee meals. We are allowed to bring in a mini frig and a microwave.

The Job offer tells you about standing 8 hours a day or more. Its the job, duhhh.

I am looking forward to the Rec center ($10), waking up and going to sleep in THE Grand Canyon, attending some worship services, and basically–enjoying the gift of being there.

I do not do drugs, or consume alcohol–it seems like that may be where some of the trouble is. I enjoy guest services even though it is traditionally a low paying job.

I tend to blog and report. So, I plan to report the truth as I find it. I’ll be back with you guys in about a month:-)

Suzi, Yes let us know how it goes!

I HAVE WORKED FOR XANTERRA FOR TEN YEARS…..I FIND IN LIFE..IT IS, WHAT YOU MAKE IT….FEAR NO LABOR…AND BE GLAD IN THIS WORLD..YOU HAVE A JOB TO COMPLAIN ABOUT

Cary, Thanks for this. I would say that it isn’t a question of fearing labor. It is instead a matter of being paid appropriately for it. Of having some rights on the job. Take care, Michael Yates

My 18 year old daughter and her boyfriend are leaving at the end of July to work at the Geand canyon. I need to see a picture of these “dorm” rooms and I need to know that they will be safe. Please provide any useful feedback. Where do they go grocery shopping, where is the nearest hospital?

they’re dorm rooms, like college dorms– boxes. There is a grocery store run by Delaware North on the south rim, within walking or bike distance of any Xanterra housing. It’s not a big-city Sam’s Club, but it does have pretty much everything a normal small-town grocery store carries, and although it’s not cheap, the rates are capped by the NPS to keep them from overcharging. There are also “discount bags” available to locals that make it more affordable.

There is a walk-in clinic available on the south rim. The nearest hospital is in Flagstaff, 74 miles away. The Grand Canyon is remote, no two ways about it.

As for “knowing they will be safe,” there is no guarantee anywhere about safety– but I would feel your kid is as safe as any kid away from home for college, etc.– if she pays attention to the safety orientation (which they do give), treats the Canyon with the respect it requires, and acts with the caution that any young woman or man should when choosing peers and recreational activities.

Good post and comments. I’m a former seasonal employee of Delaware North (Yosemite), Xanterra (Grand Canyon) and Aramark, and can validate most of the claims made in both the post and responses. I wrote an article about the Yosemite concessions contract (which is up for grabs still, I think). It’s available online at http://www.thecityedition.com/Pages/Archive/2010/Yosemite_Trekker/Post_072710.html.

I also made a video about working in the national parks, including concessions jobs. This is where you’ll find lots of detail about the problems and vulnerabilities that workers face. It’s on YouTube. Use “national parks jobs” to find it from the main page of the site. You’ll see TheCityEdition as the account listed. All the best.

Hi Rosemary! It sounds like you also have a lot of great knowledge that would be instrumental in my research. I would love to speak with you. Maybe I can contact you on facebook?

My husband and I are working for DNC in Yellowstone. We arrived in May and at first we had no major complaints. The dorm is awful, but the food was good. Then the internationals arrived, way too many were hired. Now we’ve all had our hours cut to 22-26 a week. We were all told we would be working 32-35 hours a week. The internationals who borrowed money to get here as well as those depending on this job for their livelihood are in a world of hurt. The store is so understaffed that the shelves aren’t stocked and there are never enough cash registers open, the lines are huge. I’ve seen tourists walk in, see the lines and immediately leave. I can’t understand what this f**ked up company is thinking. If they doled out a few more hours to their employees, shelves would be stocked, lines would be shorter and the company would make more money.

I will agree on many of the points, at the same time, the experience working in the national parks for the international workers, is a boon to them in the long run. It gives them opportunities to improve their spoken English, an opportunity most would never receive in their home company. With better spoken English, they can work for multinational companies operating in their home country. I spent a year teaching spoken English in China after working in the national parks. Most of my students said that the ability to speak English was often 1000 more RMB per month or more. It is the opportunity for advancement. I do agree they are often treated like slave labor, but when most American employees can’t wait to run out the door when their shift ends (and later bitch about small paychecks) the international workers are asking the manager for extra hours, willing to go work in another department to get those extra hours. Some of their long hours are something they desire, some for added profit, some to break even on the investment of traveling to work there.