Radical political movements always employ slogans that encapsulate in a few powerful words the aspirations of those fighting for a new world. The French revolutionaries fought under the banner, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” words that still resonate with radicals. The first words of the U.S. Constitution—“We the People”—have quickened the hearts of generations of populist activists. Emiliano Zapata’s soldiers longed for “Tierra y Libertad,”and the peasant armies of Mao Tse Tung went to war for “Land to the Tiller.”

Radical political movements always employ slogans that encapsulate in a few powerful words the aspirations of those fighting for a new world. The French revolutionaries fought under the banner, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” words that still resonate with radicals. The first words of the U.S. Constitution—“We the People”—have quickened the hearts of generations of populist activists. Emiliano Zapata’s soldiers longed for “Tierra y Libertad,”and the peasant armies of Mao Tse Tung went to war for “Land to the Tiller.”

Every slogan has a context, circumstances that give rise to the words and make them effective. For example, when the Chinese communists were waging their long struggle against the army of Chiang Kai-shek, they relied upon mass support from peasants, who formed the base of the Red Army. China was still a largely feudal society, and peasants were brutally exploited by rich landlords. Those who worked the land wanted it, and the communists promised to give it to them. “Land to the Tillers” expressed this desire and the Party’s commitment to it. Even today, after decades of capitalist restoration, China’s rural people still have land rights won in revolutionary struggle.

The catchphrases of political upheaval are always somewhat vague. In China, there were the farmers who tilled the soil and the landlords who owned it. However, both classes included people of varying economic means. There were small, medium, and large landholders. Not all peasants lived in squalor and destitution. Yet, all landlords tended to be lumped together, and all of their land was fair game for expropriation.

The imprecise nature of political slogans is a virtue. Actual political programs do not derive from words alone but from the balance of class forces that exist at a particular point in time. What slogans do is clarify the most basic political cleavages; they help people develop the mindset most suited to active participation in whatever struggles are at hand. In China, “land to the tiller” said that those who worked the land should possess it; those who owned but did not till, should not. That some both owned and tilled did not and should not have mattered. Such complexities would have to be dealt with later, when a new constellation of class forces had come into being.

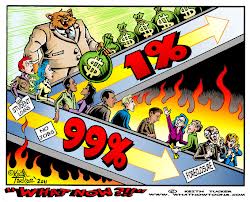

The worldwide Occupy movement that erupted in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park in September 2011 took as its watchwords, “We are the 99 %.” These words resonated with large masses of people as few others have in a long while. To understand why, it’s important to look at the context that generated the slogan.

“We are the 99%” derived its power from the devastation experienced by so many people during the Great Recession that erupted in December of 2007. The roots of this economic crisis go back to the mid-1970s, when an employer-led attack upon the working class began in response to lower corporate profit margins, the result of the declining global economic dominance of the United States. U.S. businesses faced strong economic competitors in Japan and Europe; the costs of the War in Vietnam were generating inflation and higher wages; and the brisk demand for U.S. capital goods diminished as the rest of the world completed post-Second World War reconstruction.

A weakened and class-collaborationist labor movement accommodated a rapid victory by capital, in what we typically call neoliberalism: a political project that included the deregulation of finance, privatization of public services, elimination and curtailment of social welfare programs, open attacks on unions, and routine violations of labor laws. These left working people with lower wages, less generous benefits, and growing insecurity.

The deregulation of capital markets gave rise to a host of new financial instruments, which grew by leaps and bounds as cash-strapped workers began to go into debt by borrowing against their houses and maxing out their credit cards. All of this generated growing income and wealth inequality; raised the financial sector to the commanding heights of the economy; and made production more vulnerable to financial crisis. The Great Recession was the product of the interaction of these three factors, and it generated a scale of worldwide misery not seen since the 1930s. While the downturn officially ended in June 2009, much of the working class is still mired in debt, employed in low wage/ no benefit jobs, either unemployed or fearful of job loss, and not very hopeful about the future.

While there were periodic protests against neoliberalism, it was not until the Great Recession that these broke out into mass struggle. This first emerged in the Arab Spring, but it soon spread to the entire world, from Spain to China and from Canada to Chile. In the United States, the Wisconsin Uprising of early 2011, led by public employees, inspired workers across the country, demonstrating that when pushed hard enough, in the right circumstances the working class would revolt and do things no one had imagined possible. Then, within a year of this, OWS erupted. Young people, led mainly by anarchists, took over Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan and waged protests against one of the greatest symbol of the 1%—Wall Street. When the police began to suppress the dissent, thousands of Occupy supporters descended upon the center of finance. Soon amazing displays of cooperative action and self-education deepened the struggle.

As the OWS phenomenon spread to cities and towns in the United States and then the world, the objects of the protestors’ scorn and anger increased geometrically—all those who oppressed the 99%: police, bankers, landlords, employers, universities, politicians, the media, and the military. In response, the powers that be began a coordinated campaign to slander and suppress what had the potential to disrupt both production and commerce. Ultimately, OWS encampments were closed, mainly by police force, but OWS-inspired struggles live on, and the memory of what happened is very much alive.

Critics of OWS and “We are the 99%” say that the slogan is inaccurate. I disagree. It is true that there are well-to-do people in the 99%, and there are many in the 1% who are not that rich. The cutoff yearly household income for the 1% varies, ranging from $380,000 using the Census definition of income to nearly double that using that of the Federal Reserve, which includes capital gains. In some parts of the country, $380,000 would qualify a household as rich, while in others it would not. The flip side of this is that there are many people in the 99% who are not poor. There is a big difference between an income of $379,000 (just below the Census 1% cutoff) and $20,000, the cutoff for the poorest 20 percent of households.

We could argue as well that using income to divide the 99% and the 1% is inaccurate because what matters most is wealth. Ownership of stocks, bonds, real estate, unincorporated businesses, and the like is much more skewed than income, and it is at the top of the wealth distribution that economic and political power reside. The richest 1% of households now own an astonishing 42.4 percent of net financial assets (these exclude homes and mortgage debt).

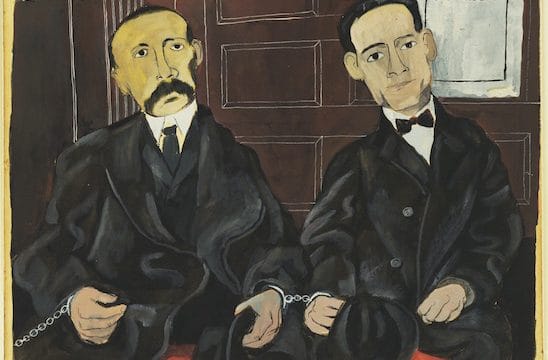

But these arguments about the accuracy of the slogan miss the point. “We are the 99%” suggests an “us versus them” politics that foreshadows the class perspective so badly needed in the United States. Those who feel unfairly maligned because, although their incomes are high, they are not rich are free to ally themselves with their poorer brethren. And those who are objectively poor are done no harm by being lumped together with those whose incomes are higher. What the slogan does is help nurture a worldview that understands that not only is inequality out of control but that the position of the 1% comes at the expense of the rest of us. To invert and paraphrase the words of Bartolomeo Vanzetti, “their triumph is our agony.” We can build upon this to create a politics that transcends the populism that passes for radicalism in the United States.

The issue here is not the literal meaning of the “1%,” but power. Whether we speak of income or wealth, power resides in the households of the 1%. They own our workplaces and control our labor. They construct nearly every aspect of society—government, media, schools, culture—to maintain and increase their dominance over us. What the slogan, “We are the 99%,” has done is bring power into the open and help change the political landscape.

Another criticism of “We are the 99%” argues that it implies a liberal politics of income redistribution and not a critique of capitalism. However, this ignores how OWS took shape. Public spaces were occupied; clashes with police ensued immediately; diverse discussions and debates took place; the movement spread rapidly across the nation and then the world; and millions of people were energized and made to feel part of something of great importance. Open air classrooms scrutinized critical issues. People learned that they could make decisions and effectively organize daily life. Those camped out in Zuccotti secured food and shelter, took care of sanitation, and solved complex problems of logistics every day.

These actions, combined with the anarchist and youthful sensibility and leadership of so much of OWS, gave rise to the posing of fundamental questions. What is democracy? Why don’t we have it? How do we dispense with ubiquitous hierarchies? Why is there so little solidarity, compassion, love? Why aren’t there enough jobs? Why is work so meaningless? Why do we devote so much of our lives to it? Why are we obsessed with making money and consuming things? Why are we destroying the environment that sustains us? Why does our government wage war against ordinary people, the 99%, all over the globe? These questions cannot be answered and the issues they raise resolved by more progressive taxes or a few expanded social welfare programs.

Our collective future is grim. Under our current political economic system, none of our major problems can be solved. Insecurity, inequality, and environmental destruction will get worse unless we take radical actions, repeatedly, for as long as necessary. OWS and “We are the 99%” were, and continue to be, ingenious interventions in what promises to be an era of growing class struggles. Other slogans will supplement “We are the 99%,” but I hope that the idea that “we are the many, they are the few” remains foremost in our minds as we combat our class enemies.

*This essay was published on counterpunch: http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/02/27/occupy-wall-street-and-the-significance-of-political-slogans/ A different version of the argument appeared in the Winter 2013 issue of New Labor Forum.

You are fighting the good fight, but the battle was lost a long, long time ago. Vacuous slogans that comfort the American middle class into faux victimology, when they (we) are leagues, houses, mortgages, vacations, and votes away from the terrible horror of the poor, was and remains offensive.

Without an Occupy candidate, without an Occupy triumph over a corporation, without social consequence (some lessening of elite pwoer) after all that rhetoric, the path looks more than grim, on all sides.

You’ve heard from with this nihilist angle before, and I’m sure this just gets tiring, but you are too much on target with your critiques for me just to let it go, and just say watch the socio-political carnage ahead.

The phrase “vacuous slogans” in the reply above suggests that the writer did not even read Michael’s argument, which deals precisely with the Non-vacuousness of slogans. The crafting of slogans is perhaps the most difficult and most important step in mobilizing people for mass struggle. Michael does point out that complexities must be worked out later. But that _begins_ to happen from the earliest stages of any movement, and exploring the complexities behind the slogan is precisely the process of political education.

In any case, I am disappointed to see that this important blog post has not elicited more discussion.

I read the post, and simply disagree. A vacuous slogan it was, and if 99% Just Won’t Do has some, delicate staying power, so do insipid ad lines. One of my favorites from the early 80’s – AT&T: The System is the Solution.

Feel free to continue insisting on slogans as protest, but others may not go for these chanting impulse.

I agree- comments sections are going nowhere, mostly due to the debased nature of modern discourse – what’s wrong with objections, criticism, opinions? Who has the full handle on everything?

Resentment of the rich is a trope of human history that dates back to when Og had more women and bigger and better clubs and rocks than Thak. A related trope is stating that those who have wealth MUST have acquired it in some dishonest, devious, and/or evil fashion. This accomplishes two extremely useful purposes for the 99%er sign-waver: 1. I’m not as rich as that 1% bastard, not because I’m not as smart or didn’t work as hard, but rather, because due to my moral superiority, I have been unwilling to become a capitalist exploiter of unwilling wage slaves (or to participate in that eeeevil system at all, i.e., work); 2. Due to the moral bankruptcy of the 1%, it is not only acceptable but a MORAL IMPERATIVE to forcibly deprive the 1% of their wealth.

I realize how tidy, as well as how appealing, this way of thinking is, and I even partially sympathize with it, but it has the same flaw that dates back to the ravings of Karl Marx: if you strip the rich of their wealth, it is unlikely that they will continue to produce that wealth again; after all, they’re not stupid. Then, to continue to support the seizure-of-assets paradigm, we will have to continually redefine “wealth,” until the State will eventually be confiscating the “excess” shoes of everyone who owns more than one pair.

Yes, indeedy, there is income and wealth inequality, but when you consider the societies in recent human history wherein there was/is the most equality of wealth–Soviet Union, Somalia, China, Cuba–it doesn’t seem like a desirable human state. I think, in fact, that a perfectly equal society would be a perfect hell. Also–impoverished. Yes, yes, yes, capitalism is a nasty, greedy, exploitative, soul-destroying blight on the face of humanity, more morally bankrupt than Naziism and more evil than torturing and raping Girl Scouts. But it HAS proved to be an effective engine for creating wealth, and not just for the eeeeeevil corporations and the Scrooge McDucks who run them. The ordinary schmuck is better off than he ever has been in human history, largely due to capitalism. The po’ folks in the ghetto today live better than an 18th-century king ever did. That, to me, defines progress.

Joe, these are the ravings of a fool.But thanks for exposing your foolishness. Always appreciated.

Michael my man, your collective writings are more evidence of lunacy than anything I could ever write. However, I won’t stoop to insulting YOU just because you and I radically disagree. Your worldview is tragically distorted–and I say “tragically” because you’re a manifestly intelligent man–but you are nonetheless entitled to that view as well as to express it. I don’t, however, think that entitlement extends to lifting your hind leg and peeing on anyone who doesn’t share your outlook. Though your recent fulsome praise of the late Hugo Chavez–the power-mad, barely sane leader of what was a classic South-American kleptocracy, whom you seem to have chosen to exalt to mythic status simply because of his rabid anti-US (and often, anti-sanity) stance–means that you probably feel constrained to pee on a LOT of people.

Brilliant, Michael – what a lunatic gasbag (though probably an upright, voting “citizen”) – it’s heartening to see the line “the State will eventually be confiscating the “excess” shoes of everyone who owns more than one pair” given such a dignified response.

Ah, yes: “lunatic” = “anyone who has the effrontery to disagree with MOI.”

I would clasify anyone who exalts Hugo Chavez and Fidel Castro as a lunatic, in that megalomaniac mass murderers are generally not worthy of exaltation. Also, Comrade Yates claims to be a Marxist and an economist; you actually can’t be both, as being one contradicts being the other.

Thankfully, Yates remains on the far, far, far left fringe of both society and human thought. I’m actually a liberal by any definition of the term, but I nonetheless realize the childishly obvious–that Marx was a crackpot and his theories were diarrhea. I guess Comrade Yates thinks I’m a rightist conservative; by contrast, I suppose, I am, much in the way that to a person standing on the North Pole, everyone is south of him.