A recent op-ed in the New York Times described the construction of “the mother of all luxury property developments,” on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, complete with branches of famous museums and a university. We learn that:

Saadiyat’s extraordinary offer to the buyers of its opulent villas is that they will be able to stroll to the Guggenheim Museum, the Louvre and a new national museum partnered with the British Museum. A clutch of lustrous architects —Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid, Rafael Viñoly and Norman Foster—have been lured with princely sums to design these buildings. New York University. . . will join the museums when its satellite campus opens later this year.

As might be expected, underlying this monument to excess is an army of laborers from Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal. These desperate souls arrive heavily indebted to recruiters and those who pay their passage, only to be brutally exploited by sponsoring employers, who confiscate their passports. It is a system of semi-slave labor; workers are not free to leave, even if they have not been paid.

There has been no shortage of architects and other members of the “creative class” willing to ignore the human misery and do the planning and designing, curate the museums, and administrate or teach in the university. The same has been true for buyers of the “opulent villas.” One of the “lustrous architects” cited above, Zaha Hadid, also designed the 2022 World Cup soccer stadium in Qatar. In the past two years nearly 1,000 south Asian workers have died building it. When asked to comment on these startling numbers, she said,

I have nothing to do with the workers. I think that’s an issue the government—if there’s a problem—should pick up. Hopefully, these things will be resolved. . . . I’m not taking it lightly but I think it’s for the government to look to take care of. It’s not my duty as an architect to look at it. I cannot do anything about it because I have no power to do anything about it. I think it’s a problem anywhere in the world. But, as I said, I think there are discrepancies all over the world.

I have heard comments like Hadid’s before. Billionaire George Soros says that his currency speculations are “amoral,” even though they have wreaked havoc on the poorest people in entire countries. It’s not his fault governments haven’t constrained his power to do whatever he wants with his cash. If he doesn’t, someone else will. [This is the implication of Soros’s answers to questions posed to him on 60 Minutes, December 20, 1998.] Once at a faculty meeting, a colleague opposed our efforts to get the university to support the boycott of South Africa by divesting its stock holdings in companies that did business with the apartheid state. He said that there were problems everywhere, and we couldn’t solve them all, so why single out South Africa. That those waging war against the brutally racist government had asked us to support them through a divestment campaign, that this was a problem we could address, hadn’t entered his mind. On another occasion, I suggested to the dean, a physicist by training, that scientists had an obligation to consider the uses to which their researches might be put. He replied that this was none of a scientist’s concern.

How is it possible that intelligent, well-educated people can ignore obvious human wretchedness, even when, in the case of Ms. Hadid, it is right in front of her? Soros knows what he does is bad for society. My faculty colleague was a Jew who was quick to condemn anti-Semitism. Surely he must have seen the similarities between the inhuman treatment of Jews and that of black South Africans. My physicist dean must have been aware of the unease with which Einstein participated in the development of the atomic bomb, and his opposition to nuclear arms after the Second World War.

It is possible that Hadid, Soros, my coworker, and the dean have uniquely flawed characters; perhaps they pathologically revel in the degradation of others. However, readers can probably think of like examples, and if we examine our own actions, no doubt we have at one time or another said similar things or at least thought them.

Maybe something different is at work. All of the transactions that will bring the Saadiyat Island venture to fruition occur in impersonal markets. They involve the transfer of money from buyers to sellers. And as the Romans said, pecunia non olet. Money has no smell. The plight of the workers is outside the purview of those who sell their architectural services or purchase the palatial homes; it is not a part of the market exchanges in which they are involved. These elite managers and consumers spend and receive cash in isolation from anything else. They cannot “smell” the suffering of those who toil so that their artistic conceptions and consumption dreams can be realized.

Our relationships with one another are often hidden behind the veil of the marketplace, covered by a shroud of money. We buy and consume goods and services without knowing who made them or under what conditions. Someone suffers so that we can have nice things, but the market obscures this. We are simply looking for the best deal; it is not our fault that exploitation lies beneath the surface of our buying and selling. We cannot be held responsible for this. Managers of corporations and political elites hire “creators,” who in turn hire contractors, who then employ subcontractors, until finally those who sacrifice their bodies and minds are paid (sometimes) to do the hard labor. All along the line, markets and the money that makes them function seem to rule, coldly and impersonally, beyond anyone’s control, or responsibility. Perhaps it is no wonder that Ms. Hadid spoke as she did.

Yet, not everyone wears blinders. For example, protests against conditions on Saadiyat Island have been made by artists and writers, through a coalition, Gulf Labor; recently some members occupied the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan. They hope that their efforts will compel the museum to raise labor standards. The Occupy Wall Street movement has fought to stop home evictions and to have student college debt forgiven. Chinese workers are demanding the right to have independent labor unions to end the factory conditions that have led workers to commit suicide.

Those who struggle against the victimization of workers are typically left-wing in their political outlook. What do they think is needed to create a society in which we have obligations for our fellow human beings, that, as the Industrial Workers of the World say, an injury to one is an injury to all? Most confine themselves to political and economic agitations that might generate the freedom of those who labor to sell their capacity to work to the highest bidder, to form labor unions, and to enjoy full political rights.

While these measures are both necessary and admirable, they presume the continued existence of markets and the rule of money that accompanies it, the very things that provide cover for the horrors that define our daily labors. This acceptance of markets has been embraced recently even by self-proclaimed Marxists. Ben Kunkel, the writer, founder of the magazine n+1, and author of a book on radical political economy, said in a recent interview:

So at least in theory, you could have a market economy where everybody receives the same income. It might not work for other reasons — because there would be, I suppose, no incentive at all to do a better job than someone else in terms of what you received in compensation — but at least in theory, there’s no incompatibility between an absolute equality of income, and absolute freedom in terms of how that income’s spent.

Here we have a man of the left equating freedom with consuming and using equal income as an ultimate goal for a good society. By suggesting that we can leave markets intact as we fight to build a new world, Kunkel ignores the truth that market relationships, what Marx called the “cash nexus,” are an integral part of capitalism. The labor market, in which our labor power is bought and sold as if it was a lump of coal or a piece of machinery, cannot be allowed to exist if we want to end exploitation. This market, like all others, is profoundly alienating, allowing us to both fail to grasp our subservience to the capitalists and to deny our complicity in a vicious and deadly system. And as Marx scholar and economist Michael Lebowitz argues, we create ourselves as we produce and distribute society’s output. If goods and services are made and dispensed through markets, the individualistic, self-serving behavior that these demand is bound to infiltrate our being. We will continue to find ourselves alienated from our labor, the products of our labor, and one another. We will be bound to make ourselves into human beings incapable of cooperative, collective productive relationships. Markets inevitably force us to act as individuals, responding to monetary incentives. We cannot liberate ourselves while maintaining a wage system and the selling of goods and services for a profit.

Markets work well for the rich: those who rule Abu Dhabi, those who own the banks that finance the developments, those who sit on the boards of the elite museums and universities, all who own large amounts of capital. Over the past forty years, markets have made the wealthy rich beyond their wildest dreams, with an ever-growing power to control markets and our lives. What this means is that the liberal, social democratic struggles that met with some success in the past are not likely to be effective now. Sit-ins at museums and boycotts might provide temporary relief for the downtrodden, but not enough to matter much. Of course, some relief is better than none, but capital will always find ways to avoid doing what is contrary to its interests. The supply of exploitable labor is nearly limitless, and just when you think the degradation of men, women, and children has reached its nadir, new debasements are devised.

We live in a world where the domination of markets is nearly total, in every country and in all parts of our lives. If humanity is somehow to move itself toward liberation, toward control over that which makes us human—the social nature of our labor—we must stop accepting half-measures. Higher wages, more equal incomes, better social services, even an end to the conditions under which men work on Saadiyat Island, won’t be nearly enough if we keep buying and selling.

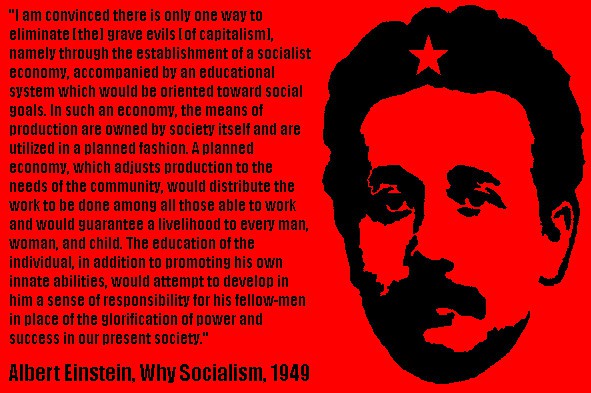

The precarious situation facing billions of the world’s inhabitants every day demands our attention. There is always some awful problem that requires opposition. Yet, it is apparent, perhaps more than at any time since the industrial revolution, that the root cause of these problems is the capitalist system. The combination of the market veil and workplace exploitation has to be destroyed and replaced with a cooperative and collective mode of production and distribution. Therefore, whenever and wherever we can, it is incumbent upon us to name the system, to say forthrightly that capitalism is the cause of most of our misery. We must do this no matter the venue, whether the mainstream media, a classroom, a union meeting, or a training session. And we must bring this message to workers, peasants, students, everyone, whenever the opportunity presents itself.

** Copyright, Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission. This essay appeared originally at http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/23118-markets-are-the-problem-not-the-solution

A wonderful sermon, friend, but so many people fear to rend the market veil.

You said it, brother. This is right on the money. No pun intended.

Michael, Thanks for the kind words. I re-read the essay last night and thought it wasn’t half bad. This is not always the case.

A great day’s work that hits the nail squarely on the head. The cash nexus of capitalism makes most of us enablers and collaborators, even the well meaning. The only solution is to throw the monster out with the bath water: socialism or barbarism is still our only choice. ~Quiller, snorting and spitting on the floor for emphasis

Thanks, Gulf Mann. The system forces us to act in ways that simply reinforce that which we oppose. It is hard to break away, which is why the task of the working class is so daunting.