Today is the 87th anniversary of the state-sponsored murder of Sacco and Vanzetti. What follows is a film review and essay that I wrote a few years ago. I think you will find it interesting. There are links for further study.

“If it had not been for this thing, I might have lived out my life talking at street corners to scorning men. I might have died, unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, justice, for man’s understanding of man, as now we do by accident. Our words—our lives—our pains—nothing! The taking of our lives—lives of a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler— all! That last moment belong to us—that agony is our triumph.” —Bartolomeo Vanzetti, comment to a reporter before his execution (1927)

In the spring of 1920 two Italian immigrants, Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, were accused of the April 15 robbery of the payroll of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Factories in South Braintree, Massachusetts and the murders of the paymaster Frederick A. Parmenter and his guard Alessandro Beradelli. The accused were anarchists, followers of Luigi Galleani, a prominent Italian radical, who advocated violence against the state. At the start of the trial the Great Red Scare was in full swing, fueled by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the growth of radical sentiment in the United States, and the draconian laws enacted during the First World War. Immigrants, painted as anti-American radicals, bore the brunt of it, harassed, arrested, and summarily deported on the flimsiest of charges. After a spectacularly unfair trial, in which judge Webster Thayer displayed blatant bias against the defendants and prosecutor Frederick Katzman willfully violated much of the canon of legal ethics, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of murder. Between their conviction on June 14, 1921 and their execution on August 23, 1927, the case of Sacco and Vanzetti became a cause célèbre in the United States and around the world.

In the spring of 1920 two Italian immigrants, Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, were accused of the April 15 robbery of the payroll of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Factories in South Braintree, Massachusetts and the murders of the paymaster Frederick A. Parmenter and his guard Alessandro Beradelli. The accused were anarchists, followers of Luigi Galleani, a prominent Italian radical, who advocated violence against the state. At the start of the trial the Great Red Scare was in full swing, fueled by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the growth of radical sentiment in the United States, and the draconian laws enacted during the First World War. Immigrants, painted as anti-American radicals, bore the brunt of it, harassed, arrested, and summarily deported on the flimsiest of charges. After a spectacularly unfair trial, in which judge Webster Thayer displayed blatant bias against the defendants and prosecutor Frederick Katzman willfully violated much of the canon of legal ethics, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of murder. Between their conviction on June 14, 1921 and their execution on August 23, 1927, the case of Sacco and Vanzetti became a cause célèbre in the United States and around the world.

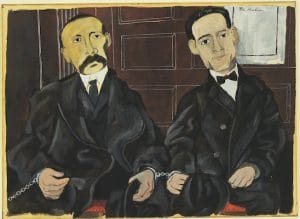

The lives and deaths of Sacco and Vanzetti have inspired hundreds of works of artistic expression: more than one hundred poems (see “Fish Peddler and Cobbler” by Kenneth Rexroth, “Justice Denied in Massachusetts” by Edna St. Vincent Millay, and “They Are Dead Now” by John Dos Passos), six plays (including the verse play “Winterset” by Maxwell Anderson), numerous essays (including Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Never-Ending Wrong”), many works of art (“The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” by Ben Shahn is probably the best-known; this is the image at the top of this post), countless songs (including Woody Guthrie’s “Two Good Men” and Joan Baez’s of “The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti”), and films (especially Sacco e Vanzetti [1971], directed by Giuliano Montaldo and with Baez on the soundtrack).

The latest entrant into the Sacco and Vanzetti pantheon is the fine film, Sacco and Vanzetti, by film-maker Peter Miller, the first full-length documentary treatment of this infamous case. I was in Santa Fe, New Mexico the first week of December, during the fourth month of an extended road trip through the southwest, and I noticed that the Santa Fe Film Festival would soon be in progress. I looked over the long list of films to be shown, and I was drawn to Miller’s. I had seen and loved the Montaldo movie, and like so many others, I had been fascinated, horrified, and deeply moved by what happened to Sacco and Vanzetti. I had also heard good things about another Miller film, The Internationale, about the famous radical anthem, and this heightened my interest.

Sacco and Vanzetti is a straightforward documentary. It tells its story well and accurately; it is superbly researched. Archival footage, photographs, art work, and a few clips from the Montaldo picture are interspersed with commentaries by historians and authors such as Howard Zinn, Mary Anne Trasciatti, Nunzio Pernicone, and Studs Terkel, as well as local experts, who show us the places where Nicola and Bartolomeo lived and worked in Massachusetts and where the robbery and murders they were accused of took place. Excerpts from the powerful letters of Sacco and Vanzetti are read dramatically and idiomatically by actors John Turturro (Vanzetti) and Tony Shalhoub (Sacco). It is apparent that Miller has immersed himself in the case, reading both the primary and secondary literature and interviewing everyone in both the United States and Italy who might add interest and drama to his documentary. The daughter of murdered paymaster Parmenter was interviewed, and though she doesn’t seem to know much of the details of the events that scarred her childhood, she tells an interesting story about how a college teacher who didn’t know who she was had her read a poem about Sacco and Vanzetti. I asked Peter Miller a question about her after the showing, and he said that her mother died not long after her father was killed, so her childhood was extremely traumatized. Relatives of Sacco and Vanzetti were also interviewed, but only a niece of Sacco from Italy appears on screen.

The film provides interesting information about the backgrounds of Sacco and Vanzetti and the political economy of the time, and this, along with an overview of what happened, gets viewers up to speed quickly, especially important for those unfamiliar with the case. We learn that the two men came from opposite ends of Italy. Vanzetti was born on June 1, 1888 in northwest Italy, in the rural Piemonte town of Villafalleto, sixty kilometers south of the industrial city of Turin. His parents were farmers, but in his youth, his father apprenticed him to a baker. As Marx tells us in the chapter on “The Working Day” in Capital, Vol. I, a baker lived a life of unremitting and poorly paid toil, and Vanzetti soon enough abandoned it. The death of his mother devastated him and no doubt helped spur his decision to emigrate. He came to the United States in 1908, and after drifting from job to job in industrial America, took up the employment he had at the time of his arrest — a fish peddler. Vanzetti was studious and well-read. He was a bachelor, and all who knew him commented on his kind and gentle nature. Nicola Sacco was born on April 22, 1891 in the Puglia town of Torremaggiore in southeast Italy, like Vanzetti the son of farmers. (His father was also an olive oil dealer). He arrived in the United States also in 1908. He became a skilled shoe worker, so trusted by his employer that he sometimes served as night watchman. He married and had a son, was a devoted husband and father, and spent much of his free time gardening (a passion among Italians), giving extra produce to his employer to distribute to the poor.

Between 1880 and 1920, nearly 4,000,000 immigrants, including many of my ancestors, came from Italy to the United States. Most, but by no means all, of the newcomers were from the impoverished rural areas of southern Italy, and they came here because economic and political conditions in their homeland had become increasingly untenable. Many hoped to return, but for most the United States became a permanent home. The Italians, facing extreme discrimination and hostility in their new country and unable yet to speak English, took whatever jobs they could find and lived in crowded urban tenements. They found life in the United States harsh and brutal. Jacob Riis, in How the Other Half Lives, described typical living conditions:

In a room not thirteen feet either way slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor. A kerosene lamp burned dimly in the fearful atmosphere, probably to guide other and later arrivals to their beds, for it was only just past midnight. A baby’s fretful wail came from an adjoining hall-room, where, in the semi-darkness, three recumbent figures could be made out. The apartment was one of three in two adjoining buildings we had found, within half an hour, similarly crowded. Most of the men were lodgers, who slept there for five cents a spot.

Work was no better. My great-uncle, Alberto Benigni, who emigrated with his family to the United States from the far north of Italy during this period, went to work in a central Pennsylvania coal mine at the age of nine. A Library of Congress website tells us that “At the turn of the 20th century, southern Italian immigrants were among the lowest-paid workers in the United States. Child labor was common, and even small children often went to work in factories, mines, and farms, or sold newspapers on city streets.”

Those who live through the transition from a land-based peasant economy to capitalism experience it as a violent and alien blow to their lives. As E.P. Thompson argues in his magisterial The Making of the English Working Class, capitalism is not just an assault on the way things are produced and exchanged, it is also an attack on an existing culture. It turns the world upside down, leaving people wondering what is happening to them and seeking any kind of relief. All sorts of responses occur: religious millenarianism, destruction of machinery, banditry, riots, strikes, and flight. Later, workers form unions and political organizations. Many of the Italian immigrants in the United States were horrified by what they saw and endured here. The more thoughtful, compassionate, courageous, and angry among them took action. Sacco and Vanzetti were such persons. Like many radicals from rural backgrounds in the less industrialized capitalist nations, they were attracted to anarchism. They were working-class militants, supportive of union organization, anticlerical, and opposed to all forms of state oppression. Left-wing anarchism, of the kind championed by Galleani and Carlo Tresca, appealed to them. They fervently threw themselves into the cause.

Radicalism of all stripes gained millions of adherents in the United States during the period between the Civil War and U.S. entry into the First World War: The Knights of Labor, the Western Federation of Miners, the Industrial Workers of the World, the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, and many others. Socialists challenged for power in the American Federation of Labor, and hundreds of Socialist Party members ran successfully for local and state offices. Employers and their willing accomplices in government responded to the radicals with both legal and police repression. The Bolshevik revolution, in which communists took state power in Russia, along with the First World War, heightened this repression. Wars always provide good cover for attacks on workers and their organizations, especially if the workers are immigrants — wars always involve a propaganda onslaught against the “other.” The United States enacted draconian measures to prevent any sort of opposition to the war, in either speech or deed. The great labor leader Eugene V. Debs was sentence to ten years in prison for making an antiwar speech. Sacco and Vanzetti were opposed to the war and to the conscription implemented by Congress to fill the trenches. Galleani told his members to leave the country during the war, and Sacco and Vanzetti duly exiled themselves briefly to Mexico. This sojourn was used to the prosecution’s advantage during their trial.

After the war, employers were hit with a national wave of mass strikes, such as the Great Steel Strike of 1919 and the Seattle General Strike, all of which saw the active participation of immigrant labor. These were crushed by employer and state violence, and the government initiated a concerted attack on radical “foreigners,” rounding thousands of them up in the notorious Palmer Raids, engineered by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer (whose house was bombed by anarchists).

Thus, when Sacco and Vanzetti were accused of the Braintree robbery and murders (and Vanzetti had already been arrested, convicted, and sent to prison for a failed robbery on December 24, 1919, on the flimsiest of evidence), a climate of near hysterical fear and hatred of radicals, immigrants, and militant unionists had been created by the government, so-called patriotic organizations like the American Legion, and employer front groups. In a sense, what followed was inevitable.

The film gives considerable details on the trial and appeals. These would be unbelievable were it not for the fact that unfair trials are not at all uncommon in the United States. The prosecutor had state witnesses give intentionally misleading testimony, notably on ballistic evidence. The judge was viciously biased against the defendants. He talked about the trial in unethical ways during the trial, referring to “those Italian bastards.” After the trial, he said to a friend, “Did you see what I did with those anarchist bastards the other day.” He allowed and encouraged the prosecution to attack the defendants’ patriotism and political beliefs. Prosecution witnesses gave hardly credible testimony, some of it knowingly untrue. The jury took little cognizance of the alibis Sacco and Vanzetti had and the numerous witnesses who gave credence to these, apparently believing that Italian immigrants who could not speak fluent English must be lying. Compounding the prejudices and misdeed of the judge and the prosecutor was the inept defense mounted by well-known radical lawyer Fred Moore.

Thayer was allowed by Massachusetts law to hear the first appeals. (In an interesting irony, the appeals were handled by conservative Boston lawyer William G. Thompson, while the Communist Party helped keep the case alive.) He dismissed a confession made by one of Sacco’s fellow prisoners in the Dedham jail, even though the inmate was a member of the Joe Morelli gang, which had been committing holdups in the area at the time of the South Braintree robbery, and even though the car and license plate thefts that figured prominently in it were hallmarks of the preparations of professional criminals. When massive protests, even by some members of polite society, finally forced Massachusetts governor Fuller to appoint an advisory committee, the panel, led by Harvard president Lawrence Lowell, issued a completely dishonest whitewash of Thayer and the trial. Lowell was a notorious anti-Semite, who loathed Harvard law professor Felix Frankfurter, a strong and vocal supporter of Sacco and Vanzetti. Fuller turned a deaf ear to all pleas for clemency, including a personal and tearful one made by Sacco’s wife Rosina.

The background to and details of the trial are fascinating and Miller deserves our thanks for making these clear for viewers. But Miller makes his film soar by keeping our attention focused on the defendants. For Sacco and Vanzetti were extraordinary men. They spent more than six years in prison, knowing that they were almost certain to die. Sacco’s daughter was born while he was incarcerated, and he never got to see her. Yet they took English lessons, stayed active in their defense, and kept up a voluminous correspondence. They remained fiercely faithful to one another and never abandoned either their radicalism or their humanity. Their spirit shows up most forcefully in their letters. Vanzetti was the more polished writer, and some of his letters are extraordinarily insightful and literary as can be seen in the famous excerpt quoted at the beginning of this review. But Sacco too could be moving. Here is what he wrote to his son just before he was executed. ( made into a lyric by Pete Seeger):

If nothing happens they will electrocute us right after midnight

Therefore here I am, right with you, with love and with open heart,

As I was yesterday.Don’t cry, Dante, for many, many tears have been wasted,

As your mother’s tears have been already wasted for seven years,

And never did any goodSo son, instead of crying, be strong, be brave

So as to be able to comfort your mother.And when you want to distract her from the discouraging soleness

You take her for a long walk in the quiet countryside,

Gathering flowers here and there.And resting under the shade of trees, beside the music of the waters,

The peacefulness of nature, she will enjoy it very much,

As you will surely too.But son, you must remember; Don’t use all yourself.

But down yourself, just one step, to help the weak ones at your side.The weaker ones, that cry for help, the persecuted and the victim.

They are your friends, friends of yours and mine, they are the comrades that fight,

Yes and sometimes fall.Just as your father, your father and Bartolo have fallen,

Have fought and fell yesterday, for the conquest of joy,

Of freedom for all.In the struggle of life you’ll find, you’ll find more love.

And in the struggle, you will be loved also.

At the end of Sacco and Vanzetti, some of commentators appear to be close to tears. Reading Sacco’s letter, you can see why. And you can see too why millions of people protested around the world for them.

I hope that this film will be widely distributed and seen. Not only does it offer a badly needed history lesson, but it also could not have been made at a more opportune time. The story of these heroic radicals is compelling and resonates deeply in today’s repressive political environment. The horrible injustices done to Sacco and Vanzetti are being suffered by all too many people right now. They received a grotesquely unfair trial. They suffered vicious hatred because they were immigrants. They were persecuted because they were political radicals. Only a fool would say that these are unusual occurrences today.

Sacco and Vanzetti make us proud to be human beings and prouder still to be radicals. They also force us to recommit ourselves to the struggle for human liberation. For if their agony was their triumph, it can and must be ours as well.

*This was first published in mrzine. See http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2006/yates211206.html

Well done; but mention of the Socialist Labor Party is missing from your piece. Check out page 5 of on this link from what was being said in 1927 by the “Weekly People”, official organ of the SLP: http://www.slp.org/pdf/thepeople/mar_apr_07TP.pdf

Thanks, Mike. I will read this now.

Great post. Readers should know that Hideo Kojima, one of the greatest digital artists of our time, paid homage to Sacco and Vanzetti by including this song at the very end of Metal Gear Solid 4: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOVkYAxHvkk

Another version of the song, this one adapted by Joan Baez, appeared in one of Kojima’s trailers for MGS5: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elMikUGFfqw (note that the song begins at 2:37 from the beginning). The plutocrats may own the banks, but the working people of planet Earth own the videogames!

Thanks, Dennis. I will listen to these this evening. Michael